The Arctic is an unique haven for archaeologists. The freezing temperatures have been a wonder allowing countless artifacts to remain pristinely intact in nearly 180,000 archaeological sites (Markham 2018). Unfortunately, rises in global temperature have begun to have a significant effect on the Arctic climate leading to what could be irreparable damage to its archaeological sites. While melting ice changing the landscape is one factor threatening Arctic archaeology, the fact that new land is now opening up present another danger. As these previously untouchable land becomes increasingly available, many countries have expressed an interest in the once unattainable natural resources of the land. This has created a conflict of interest between the desire to attempt to preserve the history of the Arctic and the interest in the valuable resources now accessible within the Arctic. However, before nations can decide what to do in the Arctic the question of who owns the Arctic must be answered first.

Similar to other previously inaccessible areas such as space, the idea of who has right to the land in the Arctic is a relatively new concept dating back about 100 years. One of the first claims to Arctic can be traced back to explorer Robert E. Peary. On his first successful trip to the North Pole, Peary left a note in a bottle declaring U.S. sovereignty over the region. Though the claim remained unrecognized by any nation including the U.S., his expedition did trigger a response from Canada who in 1925 passed a law effectively claiming sovereignty over a section of the Arctic. (Millstein 2016). Internationally, the biggest agreement so far on how much of the Arctic each nation has a right to is indirectly determined by the Convention of the Law on the Sea (UNCLOS). The UNCLOS specifies that members have exclusive rights to water-based natural resources within 200 miles of their coasts. Despite not being specifically aimed at the Arctic, the treaty has applied some precedent on ownership of Arctic waters.

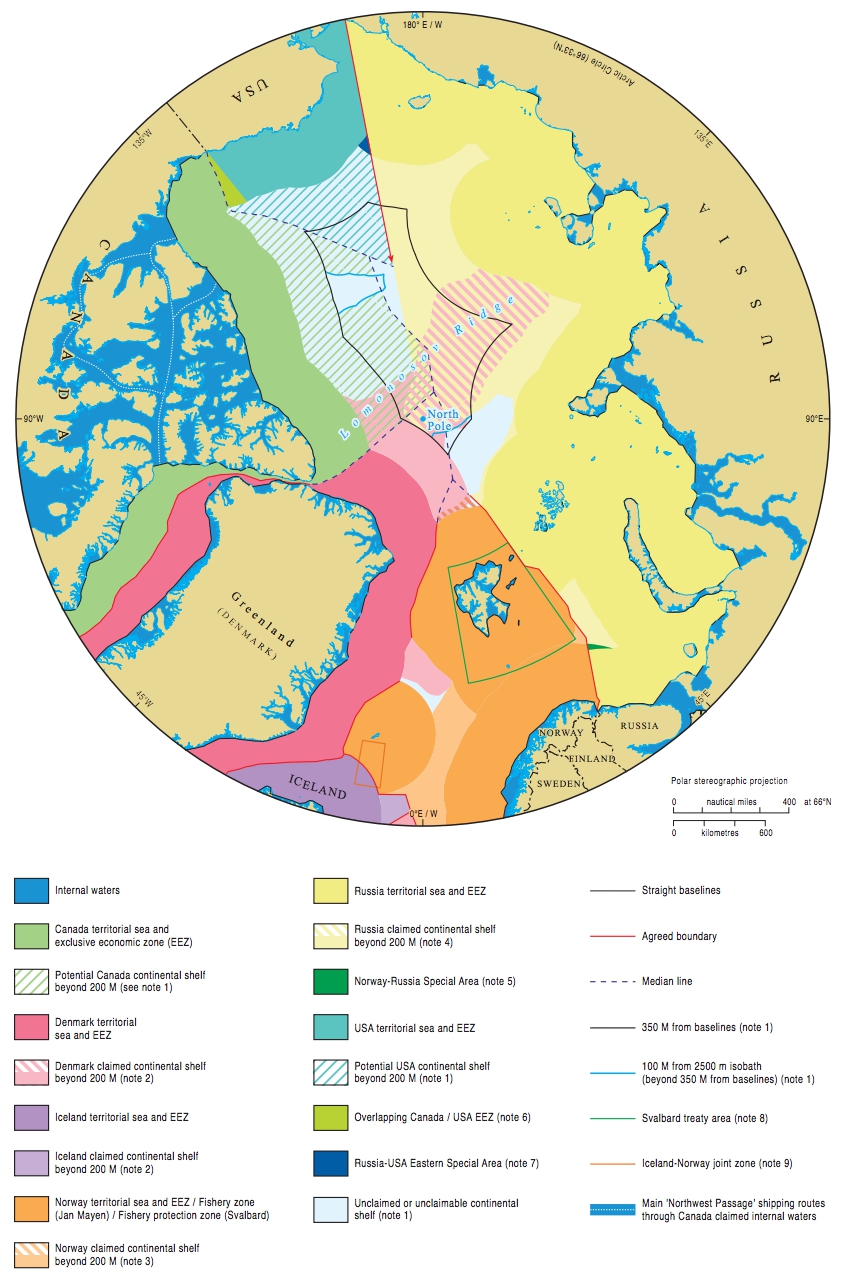

Map showing the different land claims to Arctic made by nations as of 2015 (Courtesy of Durham University)

Currently, eight nations lay claim to Arctic lands: The U.S., Canada, Denmark, Russia, Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Iceland. Studies revealing large amounts of natural gas and oil being hidden inside the territory have sparked an abrupt interest dubbed ‘scramble for the Arctic’ or more sensationally ‘the new Cold War’ (Bryce 2019). This title seems unfitting given the current history of territorial claims for Arctic. No country seems to have made much leeway in acquiring Arctic Territory. For example, Hans Island, an uninhabitable island in between Greenland and Canada, has been one of the few sources of ‘dispute’. In 1984, Canadian troops put a Canadian flag and some whiskey. A week later, it was replaced with a Danish flag and brandy leading to over 20 years of sporadic banter between the two countries. Though it is unclear who will have ownership of the Arctic in the future, for now the history of this territorial dispute is one lacking resolution, conflict, and major consequence.

Beer label of beer made in collaboration of a brewery from Canada and Denmark showing an air of levity in the Hans Island dispute. (Sherbrooke Liquor and Ugly Duck Brewing)

Further Reading :

Timeline of Arctic Territory Claims and Disputes –

https://www.stimson.org/content/evolution-arctic-territorial-claims-and-agreements-timeline-1903-present

Arctic Archaeology and the Threat it Faces from Ice Melting –

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/melting-ice-in-the-arctic-is-actually-a-nightmare-for-archaeologists/

References –

Markham, Adam 2018 Rapid Warming is Creating a Crisis for Arctic Archaeology. Union of Concerned Scientists, June 29, 2018. https://blog.ucsusa.org/adam-markham/rapid-warming-is-creating-a-crisis-for-arctic-archaeology, accessed November 10, 2019

Millstein, Seth 2016 Who owns the Arctic? And who doesn’t?. Timeline. November 28, 2016. https://timeline.com/who-owns-the-arctic-2b9513b3b2a3, accessed November 10, 2019

Bryce, Emma 2019 Who Owns the Arctic?. Live Science, October 2019. https://www.livescience.com/who-owns-the-arctic.html, accessed November 10, 2019