The bioarchaeology of care is an archaeological approach that endeavors to use physical evidence of care-giving to explore and interpret the details of past behavior, some of which may be unreachable by other means (Tilley 2011). The term was popularized in the research of Lorna Tilley and Marc Oxenham, in which they use a case study to construct an analytical framework to approach the evidence, cognizant of its social context and implications. For the most part, this care-giving is associated with individuals that are disabled or otherwise impaired; this entails limitations to activity and participation in some – or all – of their culture and lifestyle.

One particular case, that of Man Bac Burial 9, demonstrates this phenomenon thoroughly. The remains of M9 were discovered in a Neolithic cemetery site in northern Vietnam, dating back to roughly 4,000 years ago (Gorman 2012). The physical evidence reveals that M9 was paralyzed from the waist down in adolescence; his restricted upper body movement and immobilized lower body would have required extensive care in all aspects of life, and yet, M9 survived for approximately 10 more years. His survival to that point implies certain things about his community and about prehistoric society as a whole. Firstly, it implies altruism. The care-giving M9 received despite his reduced contributions to the Neolithic subsistence economy indicate that not only was there a surplus of labor and resources that would allow for his care, but also that there was compassion and a willingness in the community to do so. Additionally, there must have been a diverse range of food that would accommodate M9’s unique dietary needs emerging from immobility-associated gastrointestinal issues. M9 is one of the first prehistoric examples of long-term care-giving and survival with total disability (Tilley 2011).

Figure 1: Location of excavation site Man Bac 9. (Photograph provided by James Gorman of The New York Times, 2012).

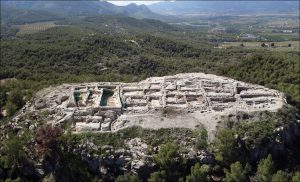

Figure 2: Modern day Man Bac, cemetery excavation site visible on the middle right. (Photograph provided by Lorna Tilley, 2011).

Alongside with the growth of the bioarchaeology of care is the corresponding debate over its viability. The archaeological evidence under discussion indicates that ancient Neolithic communities cared for their disabled members. The two responses to this are (1) the compassion argument or (2) the null hypothesis. The former believes that the care-giving was motivated by altruism and a commitment to their community members. The latter disagrees, arguing that there is not enough concrete evidence to draw conclusions about community care-giving, rather, the impaired individual must have managed on their own (Thorpe 2016, 93). The two main complications in interpreting bioarchaeology originate in our modern biases. Firstly, it may be irresponsible to retroactively attribute a motive, in this case compassion, to a culture we are completely removed from (Tilley 2011). Second, our medical understanding of particular disabilities is situated within the modern, mostly Western world, which may be completely incomparable to that of the Vietnamese Neolithic (Tilley 2011).

While archaeologists recognize these limitations, they must also acknowledge how the societal implications of care-giving enhance and add to general cultural analysis. The rejection of compassion is unproductive; instead, a more fruitful conversation could be the change of care-giving throughout the archaeological record (Thorpe 2016, 105). Overall, bioarchaeology of care can provide insights on the culture and community of an individual, while also contributing to our understanding of prehistoric society.

Further Readings:

- Oxenham, Marc F., Hirofumi Matsumura, and Nguyen Kim Dung, eds. Man Bac: The Excavation of a Neolithic Site in Northern Vietnam. Vol. 33. ANU Press, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt24hcpx.

- Halcrow, Siân E. “New Bioarchaeological Approaches to Care in the Past.” Antiquity 91, no. 358 (2017): 1101–3. doi:10.15184/aqy.2017.99.

- https://wamu.org/story/20/06/17/ancient-bones-offer-clues-to-how-long-ago-humans-cared-for-the-vulnerable/

Bibliography

Gorman, James. “Ancient Bones That Tell a Story of Compassion.” The New York Times, December 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/18/science/ancient-bones-that-tell-a-story-of-compassion.html.

Thorpe, Nick. “The Palaeolithic Compassion Debate – Alternative Projections of Modern-Day Disability into the Distant Past,” in Care in the Past: Archaeological and Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Lindsay Powell, et al., Oxbow Books, Limited, 2016. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.libproxy.vassar.edu/lib/vcl/detail.action?docID=4771018.

Tilley, Lorna and Marc F. Oxenham. “Survival against the odds: Modeling the social implications of care provision to seriously disabled individuals.” International Journal of Paleopathology, Volume 1, Issue 1, 2011, pp. 35-42, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpp.2011.02.003.