Think of all the famous museums in the United States? Which ones come to mind? I would guess your list includes any of the Smithsonian Museums, the National Gallery of Art in D.C., the American Museum of Natural History in NYC, or the National Museum of American History in D.C. However, when you think of the exhibits in the museums, what do think of? Pieces by artists such as da Vinci or Renoir would probably come to mind. Rarely would people think of works by Native American artists. This is due to a lack of awareness and education about Native American art—schools simply do not offer materials or examples of this type of art. Thus, the problem arises that people grow up without a realization of the importance of Native American art. Without Native American art, we can never tell the whole story of American art simply because Native American culture is apart of American history.

I attended a lecture last week that discussed this problem, specifically in terms of how museums handle native art. Surprisingly, most museums do in fact have collections of native art; however, rarely are they displayed to the public. If a Native American art collection is shown, it is usually exhibited in an ethnographic way, lumped together with African ‘tribal’ art. This tribal art idea arose through the colonization of American—it implies that this type of art is primitive or inferior to that of Western civilizations. Furthermore, one could almost bet that the Native American art collection only includes art up until the mid-20th century, which supports the stereotypical view that Native Americans are no longer here. These Native American collections (if displayed) are usually found in the back of the museum, sending a statement that those collections are less important and supporting the stereotype of Native Americans.

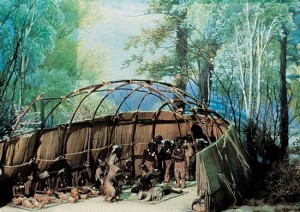

With additional research about this issue, I found an interesting article that talked about how the way museums display Native American art can be demeaning. For example, at the American Museum of Natural History, Native American art can be found right next to the dinosaur exhibit. This display placement sends a message that these people are from an uncivilized, natural world; when in fact, evidence found by archaeologists (such as Cohokia artifacts) shows that Native Americans had their own civilization, society, and technology—they were not uncivilized or savage. Furthermore, these exhibit usually have 3-D depiction of a Native American scene (a diorama). These dioramas support the belittling stereotypes about Native Americans and takes away from the value and history of the art by guessing about how that culture lived.

Therefore, the root of the problems facing Native American art comes from the way it is presented in schools and museums. Museums are being ethnographic by only displaying native art from prior to the 20th century while schools teach little about Native American art and history. Thus, both institutions create a population with little appreciation for such an important part of our history. Only with better education and awareness about Native American art can our society learn about the complete American past.

Image 1: http://www.travelportland.com/article/native-american-culture/