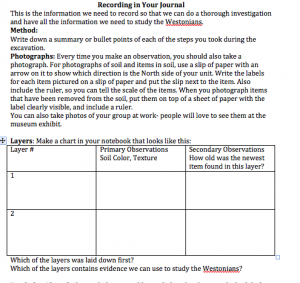

Every stone wall winding through the woods and towns of the northeastern U.S. is an archaeological site. They may be commonplace, but by studying them we can gain a glimpse into the history of the region, from the geological formation and distribution of the stones to the rise and decline of farming in the northeast with industrialization. By studying these everyday artifacts, we can look into history through the eyes of the people who lived on and worked the land, often people whose voices and lives were never written down for future generations. During the course of my research, I purposely tried to find out information about many of the often unacknowledged participants in the story of agriculture in the northeast, for example, Native Americans, immigrants, children, and slaves. Another goal for this project is to contribute to the public’s knowledge and appreciation of the study of the physical artifacts of past cultures, and by emphasizing ways that people can go out and analyze these walls for themselves, I hope to encourage people to get interested in the archaeology of their own communities.

Every stone wall winding through the woods and towns of the northeastern U.S. is an archaeological site. They may be commonplace, but by studying them we can gain a glimpse into the history of the region, from the geological formation and distribution of the stones to the rise and decline of farming in the northeast with industrialization. By studying these everyday artifacts, we can look into history through the eyes of the people who lived on and worked the land, often people whose voices and lives were never written down for future generations. During the course of my research, I purposely tried to find out information about many of the often unacknowledged participants in the story of agriculture in the northeast, for example, Native Americans, immigrants, children, and slaves. Another goal for this project is to contribute to the public’s knowledge and appreciation of the study of the physical artifacts of past cultures, and by emphasizing ways that people can go out and analyze these walls for themselves, I hope to encourage people to get interested in the archaeology of their own communities.

Without further ado:

Introducing: The Stone Walls of the Northeast

The History of Stone Walls in the Northeast

Why Are There So Many Stones in the Northeast?

Stone Walls: A Case Study