For my final project, I wanted to find a way to overcome what I viewed as two major problems in K-12 archeology education:

For my final project, I wanted to find a way to overcome what I viewed as two major problems in K-12 archeology education:

- The necessity of costly material teaching tools, be they models of artifacts, materials for reconstructing digs, or the actual cost of taking a whole class to visit a site

- The site-specificity of simulation programs, which may make it difficult to impart thematic problems in archaeology

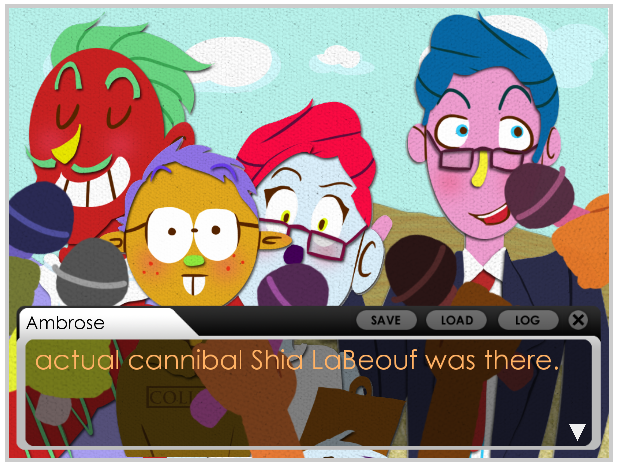

This screenshot demonstrates the user-input based interface of much of the game (Superstar Shia LaBeouf is not actually featured in this game).

Thus, the video game Practicing Praxis was born. Guided by Professor Praxis, a khaki-clad mentor, the user learns how to cooperate with different members of their field team (all of whom have very different goals), how to work with native communities, and how to ultimately present their work to the public. By using a choose-your-own-adventure format, the game simulates the reality of subjective problem solving and challenges the player to think about the stakeholders involved in each decision, and whose desires and opinions should be put above the rest– there is no right answer!

I had initially planned to give the user a letter grade at the end of the game, but working through the different scenarios made me realize that praxis (as it is implemented, not theorized) is inherently idiosyncratic, though we may hope to standardize it when it comes to ethics. Thus, I tried to constrain the chastisement in the game to instances of disrespect and thoughtlessness on facilitators’ parts as opposed to deducting points for preferring local news coverage to blogging.

This game is currently only for PCs and can be downloaded here (to install, extract all items from folder and click on the .exe file). Please forgive any lingering bugs and glitches– while I have been working on streamlining the system, this is still very much a first draft of a first attempt. Have fun!