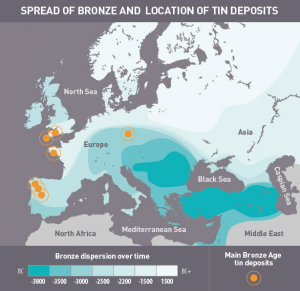

The Bronze age began 3300 BCE in the eastern Mediterranean and lasted until 1200 BCE when efficient iron smelting brought forth the dawn of the Iron Age. During this period copper and tin were smelted together to create bronze, an alloy stronger than its components and easier to create than refining iron. However, there is an unresolved question. Tin is not native in large quantities to eastern Mediterranean. Therefore, where was the tin mined?

With the advent of trace-element analysis, in which artifacts are sampled for specific rare elements, archaeologists are able to cross-reference the trace elements found in artifacts with naturally occurring concentrations across the world. For example, at shipwreck near Haifa, present-day Israel, numerous tin ingots, with Minoan symbols indicating ingots are from the bronze age, had trace elements of cobalt. Archaeologists must now find a source of tin with similar traces of Cobalt to determine the origin. Yet, they have failed to find an exact match, the closest being Cornwall, present-day England, which has concentrations of cobalt and germanium.

In addition to trace-element analysis, written sources can help narrow the tin’s possible origin. The famed Greek historian Herodotus speaks of tin originating in “the tin isles” which is thought to be the English Isles. This tin would be exported to Minoan Crete for processing into bronze. Although his claim does strengthen the possibility of a source of tin in northern Europe, Herodotus wrote his theory of the origin of tin almost a five hundred years since its primary use and admitted that he lacked an eyewitness account. Only until the Roman empire conquered the Isles did both written sources and trace-element analysis provide concrete evidence that northern tin was used in bronze production.

Ultimately, a spatial distribution of assemblages containing tin would provide the most concrete answer. Both tin and amber are commonly found in north-western Europe, but very rare in Mediterranean. Excavations in Minoan Crete and Cyprus

found jewelry made of tin and amber beads revealing a trade network between the two locations. A fall-off analysis, an analysis which shows how the quantities of traded goods decline as distance to the source increases, indicates that a down-the-line exchange system carried the tin south through present day France before Minoan merchants brought the tin across the Mediterranean to Crete. Therefore, it is probable that a route did from northern Europe did supply at least the Minoans with a source of tin.

Bibliography:

Maddin, Robert, Stech Wheeler, Tamara, Muhly, James. “Tin in the Ancient Near East Old Questions and New Finds.” Penn Museum, Vol. 15, no. 2, 1977. 35-47. http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/?p=3921. Web. 29 September, 2017.

Harms, William. “Bronze Age Source of Tin Discovered.” The University of Chicago Chronicle, vol. 13, no. 9, 1994. http://chronicle.uchicago.edu/940106/tin.shtml. Web. 29 September, 2017.

Muhly, James. “Tin Trade Routes of the Bronze Age.” Sigma Xi, vol. 61, no. 4, 1973, 404-413. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27843879. Web. 29 September, 2017.

Renfrew, Colin, and Paul Bahn. Archaeology Essentials: Theories, Methods, Practice. 3rd ed., Thames & Hudson, 2015.

Further Readings:

Monna, Fabrice & Jebrane, Ahmed & Gabillot, M & Laffont, Rémi & Specht, Marie & Bohard, Benjamin & Camizuli, Estelle & Petit, Christophe & Chateau, Carmela & Paul, Alibert. (2013). Morphometry of Middle Bronze Age palstaves. Part II – spatial distribution of shapes in two typological groups, implications for production and exportation. Journal of Archaeological Science. 40. 507-516. 10.1016/j.jas.2012.06.029.

Bernard Knapp. “Thalassocracies in Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean Trade: Making and Breaking a Myth.” World Archaeology, vol. 24, no. 3, 1993, pp. 332–347. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/124712.

Image Citations

M. Otte (2007) Vers la Préhistoire, de Boeck, Bruxelles. M. Benvenuti et al. (2003), “The “Etruscan tin”: a preliminary contribution from researches at Monte Valerio and Baratti-Populonia (Southern Tuscany, Italy)”, in A. Giumlia-Mair et al, The Problem of Early Tin, Oxford: Archaeopress. R.G. Valera & P.G. Valera, P.G. (2003), “Tin in the Mediterranean area: history and geology”, in A. Giumlia-Mair & F. Lo Schiavo, The Problem of Early Tin, Oxford: Archaeopress.

Gikeson, Mark. “Copper and Mudd.” Summer 2015, Harvey Mudd College Magazine, 9 Nov. 2015, magazine.hmc.edu/summer-2015/copper-and-mudd/.