The progression of archaeological practices as shown by the study of the Tolland Man.

In 1950, farmers Viggo and Emil Hojgaard were spading through a peat bog near the town of Tollund in Denmark. The pair found a well-preserved body laying in a sleeping position in the bog (Figure 1). The body had a rope wrapped tightly around his neck and a cap on his head (Levine, 2017). Now known as the Tollund Man, the incredible preservation of his skin, hair, and organs give the opportunity for archaeologists to look into his life from 2,300 years ago.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/a5/46a59223-d03b-41f4-83e9-8eb3ff8fa432/may2017_e09_bogbodies.jpg)

Figure 1. Tollund Man after excavation (Levine, 2017).

The Tollund Man is one of many bodies found in peat bogs across Europe. These bogs stood out from Europe’s dense forests as one of the few places where the entire area from water to sky was exposed. The acidic bogs have little oxygen and an abundance of sphagnum moss. When the moss dies, it releases a chemical that binds to nitrogen, preventing the growth of bacteria that could break down the body. The sphagnum extracts calcium from bones, which is why the flesh of bog bodies is better preserved (Levine 2017).

Because of the unique nature of the preservation of these bodies, bog bodies are a wealth of archaeological information, as tests like microCT scans of his arteries are performed on body parts that are not usually preserved (Levine, 2017). The Tollund Man has been tested and retested since his discovery in 1950, offering an insight into how archaeology methods have changed throughout the years.

The handling of the body initially showed use of the culture history approach to archaeology. In the 1960s, scientists started to use processual archaeology. Culture history focuses on when and where artifacts were found (Renfrew 2018, 25), whereas processual archaeology uses science to ask questions that connect the artifact to its place in a complex culture (Renfrew 2018, 28). The initial cataloging of the Tollund Man falls under a culture history approach, while later testing shows the progression into processual archaeology.

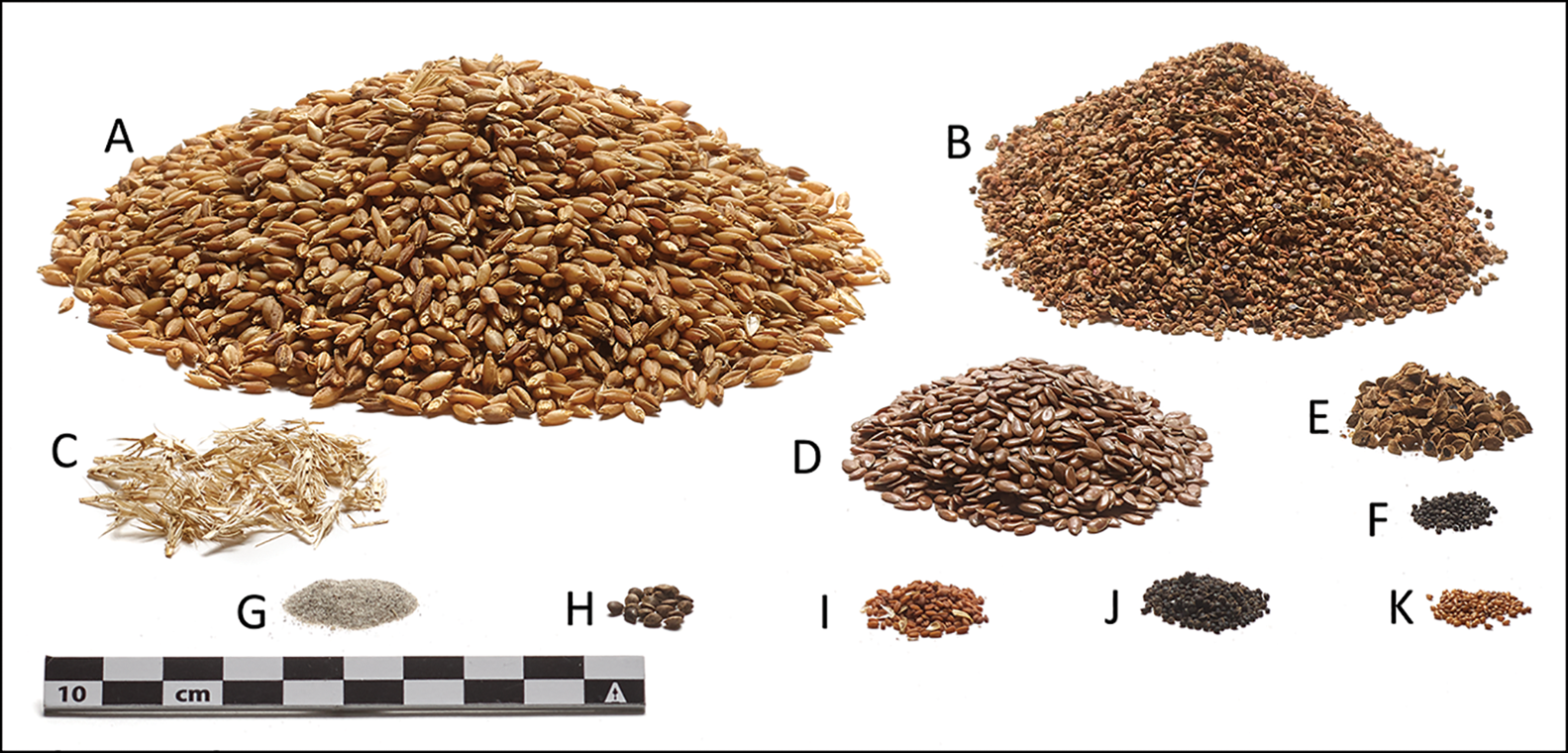

Testing right after the discovery consisted of an x-ray to the body and head, and an autopsy. Instead of using archaeology specific methods that took into consideration the age and fragility of the body, researchers used similar techniques to an autopsy of a modern body, possibly disrupting his preservation (Levine, 2017). The intestines were briefly removed and examined, but an in depth study of the contents of his stomach would not occur until later (Nielsen et al. 2021). Notably, researchers found both barley and flax, which grow in different seasons (Figure 2). The use of a processual archaeology lens revealed evidence of food storage 2,300 years ago, a find that the brevity of a culture history approach might have missed.

Figure 2. Tollund Man’s last meal (Nielsen 2021).

Moving past the culture history approach of collecting and dating artifacts has allowed archaeologists to study the larger culture surrounding the Tollund Man and bog bodies.

Further Reading:

Article:

“Why Did the Tollund Man Have to Die?”

https://www.museumsilkeborg.dk/why-did-tollund-man-have-to-die

Poem:

“The Tollund Man”

https://www.poetryinternational.com/en/poets-poems/poems/poem/103-23607_THE-TOLLUND-MAN

Podcast:

Discovery of the Tollund Man- Episode 128

https://www.archaeologypodcastnetwork.com/arch365/128

References

Djinis, Elizabeth. “Last Meal of Sacrificial Bog Body Was Surprisingly Unsurprising,

Researchers Say.” History. National Geographic, July 21, 2021. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/tollund-mans-last-meal.

Levine, Joshua. “Europe’s Famed Bog Bodies Are Starting to Reveal Their Secrets.”

Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution, May 1, 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/europe-bog-bodies-reveal-secrets-180962770/.

Nielsen, Nina H., Peter Steen Henriksen, Morten Fischer Mortensen, Renée Enevold,

Martin N. Mortensen, Carsten Scavenius, and Jan J. Enghild. “The Last Meal of Tollund Man: New Analyses of His Gut Content.” Antiquity 95, no. 383 (2021): 1195–1212. doi:10.15184/aqy.2021.98.

Renfrew, Colin, and Paul Bahn. 2018. Archaeology Essentials: Theories, Methods, and

Practice. Fourth edition. Thames & Hudson.

Image Credits

Tollund Man after excavation [online image]. Photograph by Christian Als, Smithsonian Institute.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/europe-bog-bodies-reveal-secrets-180962770/

Tollund Man’s last meal [online image]. Photograph by P.S. Henriksen, the Danish National Museum.