Amputations date back to ancient times and were as life-changing as they

are today. Performing something as complicated as amputation a thousand years ago meant that humans had to have a decent understanding of the body. The evolution of medicine suggests that agricultural societies were settled at least ten thousand years ago and stimulated major innovations surrounding medical practices. The invention and development of advanced surgical procedures were one of them. Before 2022, the oldest discovery of such an operation was found in the skeletal remains of a European Neolithic farmer. This discovery was made in Buthiers-Boulancourt of France (Maloney et al. 2022). The archeologists found that the farmer’s left forearm was surgically removed and had partially healed before death. The estimated time that this might have taken place was seven thousand years ago. The study revealed that the remains showed a medical procedure that is considered to be complicated even today, known as amputation. Amputation is the surgical removal of a body part like an arm or leg. So, the case that took place 7,000 years ago would have required a comprehensive knowledge of human anatomy and appropriate technical skills that would successfully remove a part of the body without causing more damage. Three cases of perimortem limb amputations that consisted of the severing of both hands and feet of three adult males were also reported in the archaeological literature some years back (Fernandes et al. 2017). The skeletons were from the medieval Portuguese necropolis. After studying the lesions, patterns, and location, it was concluded that the amputations were likely a result of judicial punishment during the medieval times in Estremoz city. Another case of a male with trans metatarsal amputation of both forefeet was found in England. However, this case does not infer a deliberate surgical amputation. A recent study shows amputation performed on a child that is believed to have taken place almost 31,000 years ago. The skeletal remains were found in Borneo, Papua New Guinea. This individual had their left lower leg and left foot amputated. The individual underwent amputation at a very young age and is believed to have survived the surgery and lived for around another nine years. Navigating veins, arteries, and tissues to make sure the wound was clean and had no other complications meant the people had knowledge, experience, and materials for performing the procedure (Blake 2022). This discovery suggests that amputations were performed far earlier than originally believed, and further archaeological surveys may lead to many other similar discoveries in the future. Overall, these findings help us better understand the archaeology of seemingly undocumented times.

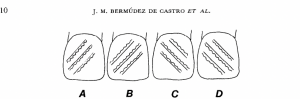

Figure 1: Archaeological discovery in Borneo showing left and right legs, with an absent lower part of the left leg along with the left foot. (NPR 2022)

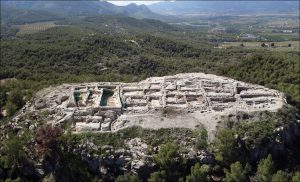

Figure 2: Tim Maloney (a professor) taking a closer look at the bones during excavation at the Liang Tebo cave located in Borneo. (NPR 2022)

For more information surrounding amputations and anthropology, please visit:

- https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpp.2011.04.001 (A case of bilateral forefoot amputation from the Romano-British cemetery of Lankhills, Winchester, UK)

- https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/287559.pdf (The oldest amputation on a Neolithic human skeleton in France)

References:

- Blake, Elissa. 2022. “Stone Age Surgery: Earliest Evidence Of Amputation Found”. The University Of Sydney. https://www.sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2022/09/08/stone-age-surgery-earliest-evidence-of-amputation-found-archaeology

- Fernandes, Teresa, Marco Liberato, Carina Marques, and Eugénia Cunha. 2017. “Three Cases Of Feet And Hand Amputation From Medieval Estremoz, Portugal”. International Journal Of Paleopathology 18: 63-68. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2017.05.007.

- Maloney, Tim Ryan, India Ella Dilkes-Hall, Melandri Vlok, Adhi Agus Oktaviana, Pindi Setiawan, Andika Arief Drajat Priyatno, and Marlon Ririmasse et al. 2022. “Surgical Amputation Of A Limb 31,000 Years Ago In Borneo”. Nature, no. 609: 547-551. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05160-8.

- NPR. 2022. “Amputation in a 31,000-Year-Old Skeleton May Be a Sign of Prehistoric Medical Advances.” NPR, September 7, 2022, sec. Science. https://www.npr.org/2022/09/07/1121535411/31000-year-old-skeleton-amputation-surgery