Most people will recognize the guinea pig as a common, adorable household pet (Figure 1). Most people will also find it hard to imagine these fur babies being served on a plate for lunch, but that is exactly what one can find when examining the dishes and delicacies of the Andes. Locally known as cuy (coo-ee), guinea pigs were also the objects of ritual acts as some evidence has indicated (Hirst 2019; Valdez 2019; Sandweiss 1997).

Figure 1. A domestic guinea pig that is ready for Halloween. Photo by PetSmart.

Domestication of cuy could have started as early as 5000 BCE, but domestication became evident by 2500 BCE (LeFebvre 2014:18). The domesticated variant of cuy are generally bigger, have more fur colors, and have larger litter sizes, as opposed to the smaller, wild cuy that are either gray or brown (Forstadt 2001). The change in litter size and overall size, under human selection, makes sense from the perspective of cuy as a once-staple food source; in fact, many of the earliest guinea pigs have been found charred and with cut marks, showing their use as food (Sandweiss 1997:49).

Information about the roles that cuyes played in prehistoric Andean society is limited, however, by their underrepresentation in the archaeological record. Many archaeologists have fallaciously concluded that Andean diet mainly consisted of South American camelids based on this absence. It is helpful, then, that guinea pigs are still commonly being raised in Andean communities. Ethnographic accounts show that cuy feces is used as fertilizer and, after consumption of the cuy, cuy bones are often fed to dogs (Valdez 1997:897). If modern Andean families maintain the tradition of their prehistoric ancestors, this could well explain the rarity of cuy remains at Andean sites.

Figure 2. Guinea pigs are dressed up, paraded, and celebrated for a Peruvian national holiday; they will soon be eaten. Photo by The Telegraph.

Despite the relative absence of cuyes in the archaeological record, ethnographic accounts can provide insights about the role of the cuy in Andean culture. Today, a mating pair of cuyes is a typical gift to newlyweds, special guests, or children (Forstadt 2001). Rather than as pets, cuyes are treated in a similar manner to chickens with the exception that there are entire festivals dedicated to them (Figure 2).

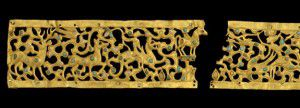

Figure 3. A buried guinea pig that is adorned with colorful strings. Photo by Lidio Valdez.

This is not to say there is no evidence of ritual behavior around cuyes in ancient Andes. Cuy effigy pots have been found from the Moche people (Hirst 2019) and, in a recent excavation, Valdez (2019) found one hundred cuy remains beneath ancient Incan buildings next to a plaza. Many of the remains had colorful strings in places of necklaces and earrings. None of them showed signs of external injury, and most of them were juvenile (Figure 3). The ritual treatment of these cuyes are similar with Spanish descriptions of Incan sacrifices of cuyes.

The attitude towards cuyes as food and not friends is no longer exclusive to South America–it is actually a trend that is following Andean expats to North America. And it’s not just exotic attraction that draws some North American patrons, but also the low-carbon impact of guinea pig husbandry as opposed to beef. A guinea pig herd “increase[s] dramatically with very little care” (Valdez 1997:896), requires very little land, and needs much less food.

Further Reading:

NPR – From Pets To Plates: Why More People Are Eating Guinea Pigs

BBC – Guinea Pigs: A popular Peruvian delicacy

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-38857881

The Spruce Eats – Traditional Andean Cuisine: Guinea Pig

https://www.thespruceeats.com/traditional-andean-cuisine-guinea-pig-3029228

References:

Forstadt, Michael S.

2001 History of the Guinea Pig. CavyHistory. Electronic Document.

cavyhistory.tripod.com

Hirst, Kris K.

2019 The History and Domestication of Guinea Pigs. ThoughtCo. Electronic Document.

www.thoughtco.com/how-why-guinea-pigs-were-domesticated-171124

LeFebvre, Michelle J. and Susan D. deFrance

2014 Guinea Pigs in the Pre-Columbian West Indies. The Journal of Island and Coastal

Archaeology 9(1):16-44.

Sandweiss, Daniel H. and Elizabeth S. Wing

1997 Ritual Rodents: The Guinea Pigs of Chincha, Peru. Journal of Field Archaeology

24(1):47-58.

Valdez, Lidio M.

2019 Inka sacrificial guinea pigs from Tambo Viejo, Peru. International Journal of

Osteoarchaeology 29:595– 601.

Valdez, Lidio M. and J. Ernesto Valdez

1997 Reconsidering the Archaeological Rarity of Guinea Pig Bones in the Central Andes.

Current Anthropology 38(5):896-898.

Images:

Figure 3. www.newsweek.com/inca-guinea-pigs-ritual-sacrifice-jewelry-1392942#slideshow/1392936