The plundering of culturally significant objects and treasure has been a prevalent issue for many years. Museums and private collectors for centuries have been taking the material culture of civilizations with no intention of returning them. Even to this day, it is not been uncommon to hear of nations condemning said institutions that are in possession of artifacts and remains that are culturally significant to them. Of course there have been some examples in recent years of repatriation, such as US art museums returning over 100 artifacts to Italy and Greece between 2005 and 2010 (La Follette 2016:670). However there is still the very prevalent issue of private collections, which is the very problem that Mexican officials face when recovering artifacts.

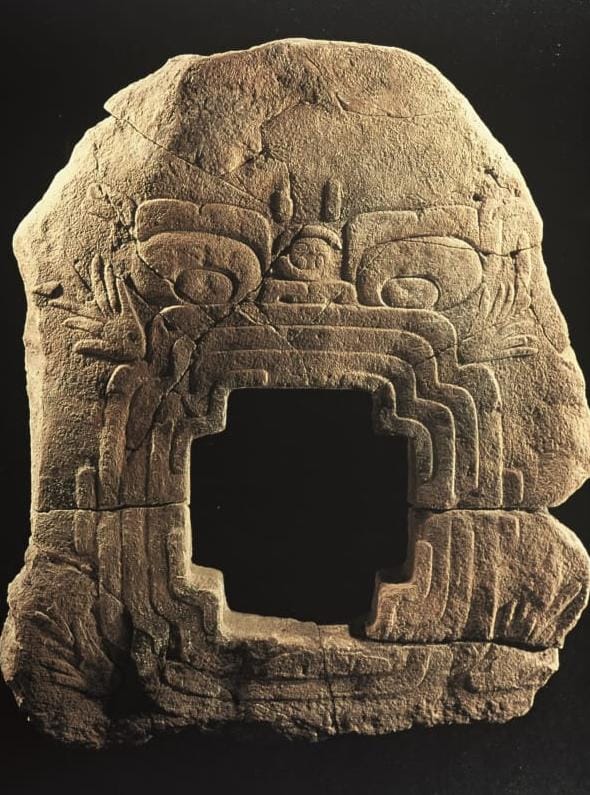

Mexico, being the former center of many civilizations such as the Olmec, Maya, and Aztecs, has an unimaginable amount of artifacts discovered and yet to be discovered. However, many of said artifacts are the targets of private collectors. One such example was “Monument 9: a 2,600-year-old carving in stone of a jaguar’s gaping face, roughly five feet wide and tall and weighing one ton” (Shortell 2023). The stone is believed to be dated from 800-400 BC or the Middle Preclassic period which is the highpoint of the Olmec site of Chalcatzingo where it was found (Exteriores 2023). Around 60 years ago the stone was looted from Chalcatzingo and brought to the United States, entering a network of private collections. The stone remained fascinating to scholars as it was believed to be used as a portal to the underworld for priests and rulers, however due to the stone’s absence and lack of pictures it was not readily studied (Stross 1996:85).

Not until recently were Mexican officials able to track down the stone and have it returned. “In March…U.S. authorities notified Mexican officials that they had seized the stone after tracking it to a warehouse in Denver. And in May the carving returned home in style, escorted by military vehicles from the airport in Cuernavaca, Mexico, to a nearby regional museum” (Shortell 2023). This is just one of many artifacts being returned to to Mexico in their repatriation campaign, aptly named “My Heritage is not for Sale”, where some 13,000 artifacts have been recovered since the campaign began in 2019.

The repatriation of these artifacts is incredibly important to Mexico’s culture. Every object returned is a piece of their rich history preserved. As successful as Mexico’s campaign is, there is still much to be done globally. Hopefully soon other nations will find success in their endeavors to recover the material culture that rightfully belongs to them.

Additional Reading on Repatriation:

https://www.wsj.com/articles/mexico-antiquities-art-return-11659127101

References:

Exteriores, S. de R. 2023. Chalcatzingo Monument 9 to be repatriated to Mexico. Retrieved from https://www.gob.mx/sre/prensa/chalcatzingo-monument-9-to-be-repatriated-to-mexico?idiom=en

Garcia, David Alire. 2023. Back in Mexico, “earth monster” sculpture points to ancient beliefs. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/back-mexico-earth-monster-sculpture-points-ancient-beliefs-2023-05-27/

La Follette, Laetitia. 2016. Looted antiquities, art museums and restitution in the United States since 1970. Journal of Contemporary History, 52(3), 669–687. doi:10.1177/0022009416641198

Shortell, David, & Carrasquero, Marian. 2023. Stone by ancient stone, Mexico recovers its lost treasures. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/23/science/archaeology-mexico-jaguar-chalcatzingo.html

Stross, Brian. (1996). The Mesoamerican Cosmic Portal: An early Zapotec example. Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 29–30, 82–101. doi:10.1086/resvn1ms20166944