Margo Gramiak

The relationship between sports history and archaeology is an interesting one, in that the two disciplines aid each other in different ways. Not only can archaeological practices better our understanding of ancient sports, but ancient sports can help us better understand ancient societies and their structures as a whole.

Archaeological practices are important for sports historians in their understanding of the games and competitions they’re studying. Being able to actually see and touch artifacts that are relevant to their studies helps tremendously in their comprehension of the sport they’re working with. In most cases, archaeology reveals the existence of the ancient sport in the first place. Needless to say, this is crucial in sports history research.

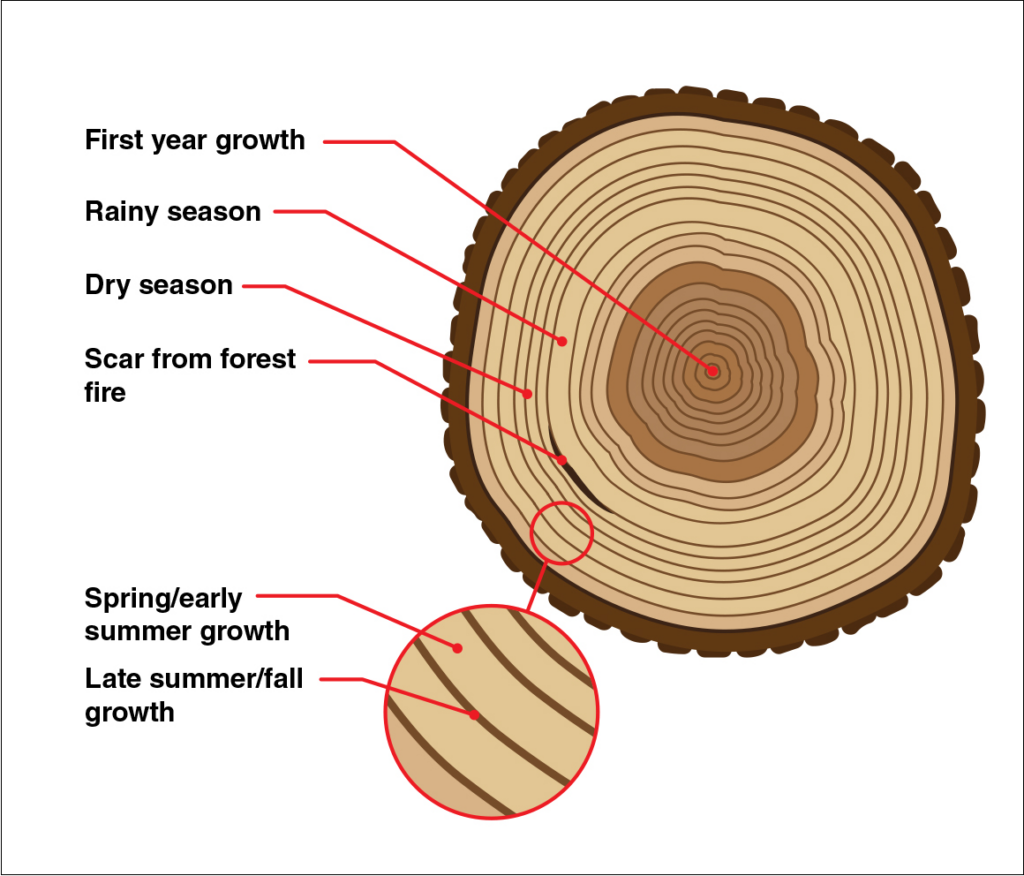

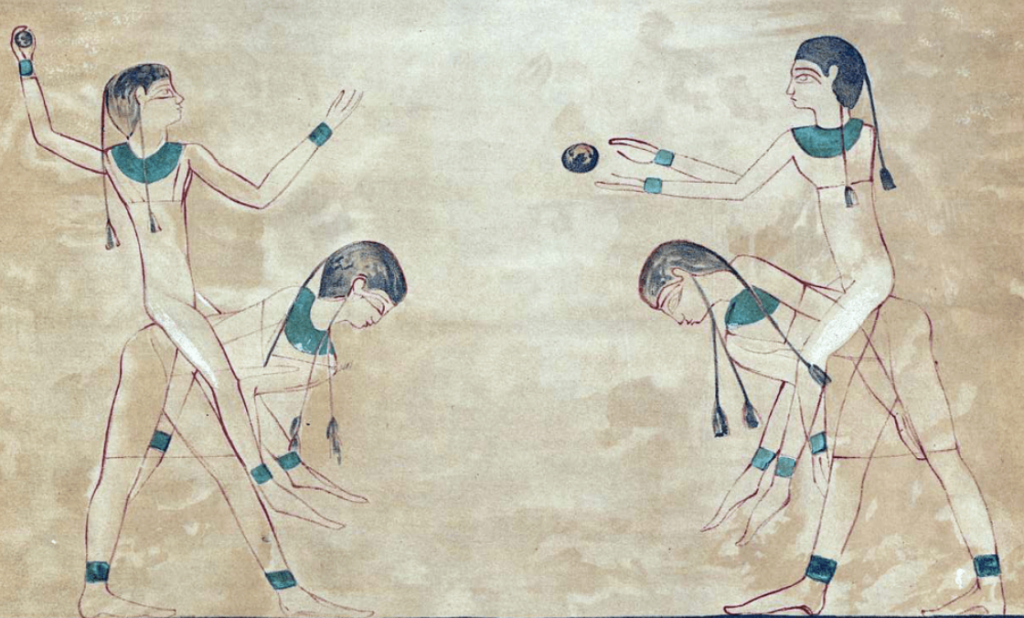

Handball, a game played in Ancient Egypt, serves as a great example of these concepts. Archaeological research allows us to understand the transformation of ancient handball, to the modern version that is still played today. Our knowledge of handball’s extensive history was prompted by the discovery of drawings in tombs of Saqqara, Egypt, that date back 5,000 years (Figure 1) (Morgan 2018). The drawings depict four girls throwing balls towards each other (Morgan 2018). These renderings allowed researchers to pinpoint the beginning of the sport. Additional discoveries of other drawings and artifacts further revealed information about the game, and how it’s been played throughout the years (Shereed 2020). The sport’s current day popularity also has helped to fill in gaps that archaeologists were unable to through just artifact analysis. A combination of archaeological research and knowledge passing has helped to reveal handball’s original rules. This is a great example of how archaeological research serves as an important tool in sports history.

Ancient sports are also important for archaeologists to better understand the societies they are studying. Oftentimes, the exploration of pastimes and activities is overlooked in the investigation of past societies. We focus on more basic aspects like where they lived, how they lived, what they ate, etc. Of course these are all important elements in any society, but why neglect the question of, “how did they have fun?” By exploring this question, so much can be revealed about a society and its dynamics.

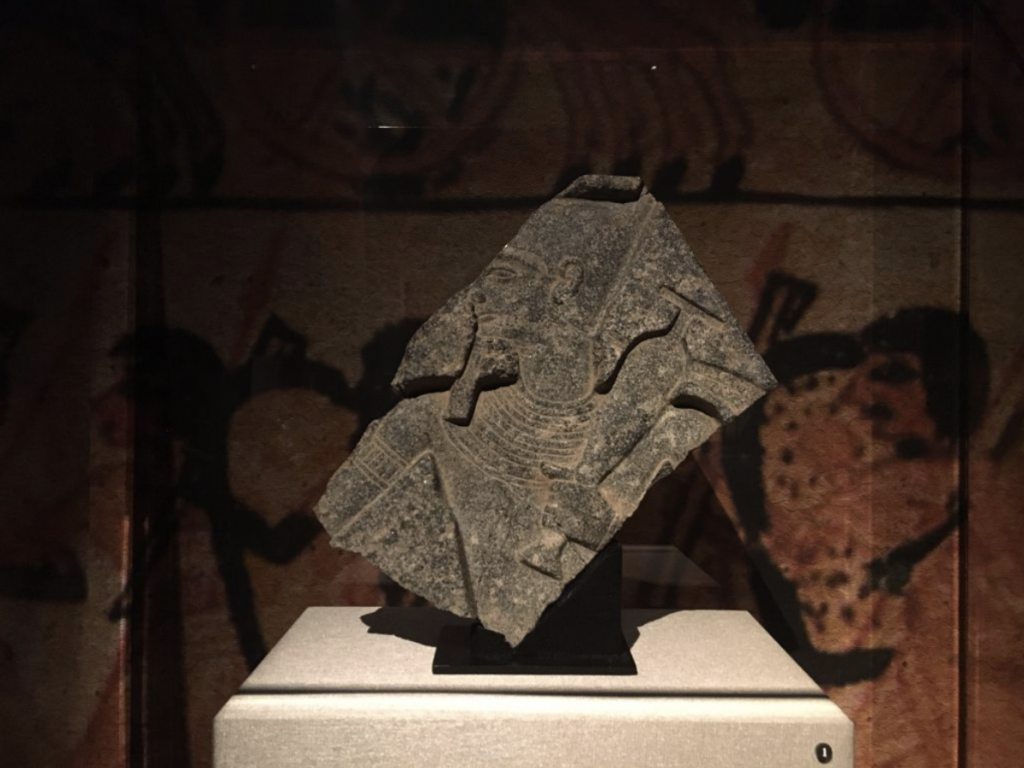

Again, take handball in Ancient Egypt for example. Archaeological data has revealed that sports in Ancient Egypt, including handball, were associated with social hierarchies (Shereed 2020). For example, evidence shows that Egyptian leaders and statesmen were the biggest fans of athletic contests, and even provided the equipment for games and events (Mark 2017). There is also evidence indicating that physical fitness and ability played a role in social status (Figure 2) (Houston Museum of Natural Science 2017). Sports were even played at celebrations like the king’s coronation, parties following military victories, religious ceremonies, and festivals (Mark 2017). Evidence of this use is prevalent in artwork (Mark 2017). Understanding the involvement of sports in Ancient Egyptian society reveals dynamics that otherwise would potentially be missed.

Even if they seem to be just “silly games,” it’s important not to neglect the significance of sports in a historical and archaeological context.

Additional Resources:

Information about ancient sports:

https://www.oldest.org/sports/sports/

Evolution and history of sports:

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/evolution-sports-from-ancient-origins-modern-day-alimo-msc

Works Cited:

Shereef, El Doaa, “Ancient Egyptian Sports and Fundamental Principles of Olympics,” Academia.edu. 2020. https://www.academia.edu/44577685/Ancient_Egyptian_Sports_and_Fundamental_Principles_of_Olympics

Morgan, Kori, “Sports Played in Ancient Egypt,” TheClassroom.com. 2018. https://www.theclassroom.com/sports-played-ancient-egypt-18187.html

Mark, Joshua, “Games, Sports & Recreation in Ancient Egypt,” WorldHistory,org. April 11, 2017. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1036/games-sports–recreation-in-ancient-egypt/

Greiner, Thomas, “How Kids Had Fun in Ancient Egypt,” NileScribes.org. March 10, 2022. https://nilescribes.org/2022/03/10/how-kids-had-fun-in-ancient-egypt/

Houston Museum of Natural Science, “Pharaonic Fitness Test,” Hmns.org. May 19, 2017. https://blog.hmns.org/2017/05/pharaonic-fitness-test/