The city of Cahokia is known for being a prehistoric site in North America made distinguishable by various earth-like mounds or pyramids spread across the Mississippi river for what is now known as the modern city of St Louis. During the twelfth century, this was a settlement with an ever-increasing population thanks to their advancements in trading, technology, and agriculture. However, before Cahokia became a prominent capital city, it was a series of many villages that regularly interacted, exchanging social and cultural ideas. As time progressed, the city of Cahokia came to be with the relocation of many people from various tribes bringing with them new cultural practices, languages, material culture, and cuisines. Cahokia’s transformation is considered a civilizing social movement, with even references to the “Big Bang” due to its explosive growth and advancement(Pauketat 2009).

Today Cahokian remains lie along the Mississippi river and are constantly threatened by modern projects and construction allowing for the deterioration of these sites. Archeologists are racing against time in efforts to preserve the monuments and study the great Cahokian city that once was. In its study and interpretation we constantly are questioning what was life like and how did these people live? What was the power dynamic? The power structure of Cahokia perplexes many as it doesn’t pertain to today’s standards and norms. With many concluding as to how welcoming and progressive the city may have seen, there were also signs of a hierarchal system in place.

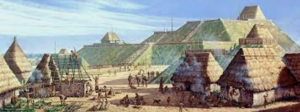

The power dynamic between families was shown with the more prominent individuals and families living atop the mounds

Evidence of the hierarchical system is constantly illustrated by the physical organization of the city and the clear disposal of resources that more prominent and wealthier families had. The leaders of the Cahokian society, often religious leaders or chiefs, lived atop the mounds and looked down on the rest of the citizens. They consolidated power not by hoarding but by giving away goods illustrating their access to and surplus of goods. Cahokia developed a ranked society with a chief and elite class overlooking workers in the lower classes(Seppa, 1997). The infrastructure of the city was divided into zones for administrative and ceremonial functions, elite compounds, residential neighborhoods, and even suburbs. One of its largest features was the central plaza encompassing nearly 40 acres which were centered for communal ceremonies and rituals that brought people together (Woods, 2007).

However, despite Cahokias ordinary hierarchical system that is often present in most if not all city-like societies, there was such peace and order in Cahokian society that it was often through minuscule differences that the presence of social classes was known. In the book “Cahokia: Ancient America’s Great City on the Mississippi”, Pauketat mentions a traveler going through the city of Cahokia at its height to illustrate the structure and organization. From the perspective of the traveler, there’s a mention of very specific styles and “rigidity of orientation”(Pauketat 2009). What can we infer from the uniformity of the houses? Does it illustrate a strict and overarching power structure or does it illustrate Cahokia’s attempt to be fair? It recalled in the book that despite there being a hierarchical system, everyone had access to resources and despite the different placements of homes, they all had very similar sizes, no matter how prominent or influential the family or individual was.

Even with a social divide, Cahokian society was progressive in its nature to provide all its citizens with the necessities of life. Although leaders of Cahokian society had more resources at their disposal, even individuals on the lower end of society had enough to live a stable life. This social infrastructure is impressive as even today’s society, which is often considered as advanced, still has individuals suffering at the hands of a large social divide in which individuals have to tackle aspects such as poverty, hunger, and illness.

Reference list:

- Pauketat, Timothy R. 2009. Cahokia: Ancient America’s Great City on the Mississippi. New York, N.Y., Viking.

- Seppa, Nathan. 1997. Metropolitan Life on the Mississippi. The WashingtonPost.https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/daily/march/12/cahokia.htm

- Woods, William I. 2007. Cahokia Mounds. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Cahokia-Mounds

Additional resources:

- https://www2.illinois.gov/dnrhistoric/Experience/Sites/Southwest/Pages/Cahokia-Mounds.aspx

- https://source.wustl.edu/2019/03/feedingcahokia/

- https://www.museum.state.il.us/iaaa/cahokiahome.htm