In Pre-Columbian times, a mighty city known as Cahokia served as a center of culture, trade, and agriculture for many indigenous societies in the Midwest. With a population in the tens of thousands, Cahokia controlled central Illinois’s Mississippi River floodplain.

Cahokian society was not restricted to this region, however. Settlers from Cahokia journeyed north as the city expanded, bringing with them Cahokia’s culture, agriculture, and architecture. One of these groups settled alongside Wisconsin’s Crawfish River around 900 CE and became a major influence on the native populations (known as the Woodland peoples) residing in the area.

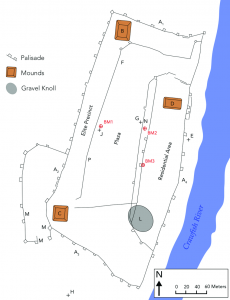

The most prominent indication that this settlement–known as Aztalan–was of Cahokian influence is the city’s layout. The town–which was home to somewhere between 500 and 600 people–was structured around four mounds, not unlike the ones in Cahokia. Three of these platforms were man-made, with the final being a natural knoll. These mounds formed a rectangle surrounding the main part of the city and its plaza. Despite agricultural damage over time, there is evidence that one of these platforms supported a temple, that a mortuary house was built atop another, and that the third man-made mound was beneath the home of a city leader. The final earthen structure likely served as a burial ground.

The city of Aztalan itself was divided into three sections: a residential area, the central plaza, and a higher ground for elites. Running through the entire city were wooden walls, but the greatest of these were the fortified palisades surrounding the Aztalan on all sides. These fences consisted of wooden posts, which were reinforced with small branches and debris, and covered in a layer of clay. The existence of these fortifications implies that the settlers may not have always had peaceful times in the Wisconsin area, possibly clashing with the aforementioned Woodland peoples.

A typical diet in Aztlan was influenced by the Crawfish River, which provided fish, mussels, and turtles. From the surrounding forest, residents were able to hunt deer, birds, and other creatures, and forage for edible plants. Using Cahokian agricultural practices, they were also able to cultivate corn, squash, and beans.

Aztalan survived for nearly 200 years, and while the circumstances surrounding its abandonment are unknown, anthropologists working in the region are attempting to shed light on the city’s end, specifically toying with the ideas of drought and warfare.

Today, what was once Aztalan is now a state park of the same name. With efforts to protect specifically the city’s mounds beginning as early as the 1920s, Aztalan State Park opened to the public in 1952, and was subsequently designated a National Landmark in 1964. Covering approximately 172 acres, the park encompasses the remains of the ancient town and its mounds as well as the surrounding area. Furthermore, excavations and restorations have taken place in the park. While two of the mounds have been extensively worked on, 80% of the area still remains to be excavated, so more discoveries are still to come.

References Cited

Dotson, Keith. 2019 “Ancient America: Aztalan Mound Site in Wisconsin.” Shadows and Light (blog), https://icatchshadows.com/ancient-america-aztalan-mound-site-in-wisconsin/, accessed November 13, 2022

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources 2022 “History: Aztalan State Park” Electronic document, https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/parks/aztalan/history, accessed November 13, 2022

Wisconsin Historical Society 2022 “Exploring the History of Atzalan: A Middle Mississippian Settlement.” Historical Essay, https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS4051, accessed November 13, 2022

Wisconsin Historical Society 2022 “Mississippi Culture and Atzalan: The Genesis of Modern Wisconsin.” Historical Essay, https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS386, accessed November 13, 2022

Further Readings: