In the 1700’s Europeans were astounded at the Hopewell Earthwork in Chillicothe, Ohio (“Hopewell Mound Group”, n.d.). They were given this name due to the burial mounds in Chillicothe, later turned into a farm owned by Mordecai Hopewell (“Who Were the Hopewell?”, n.d.). The Hopewell were assumed to have built these mounds and enclosures for defense purposes, declared by an early archeologist in 1820; however, this assumption would later be dispelled (“Hopewell Mound Group”, n.d.).

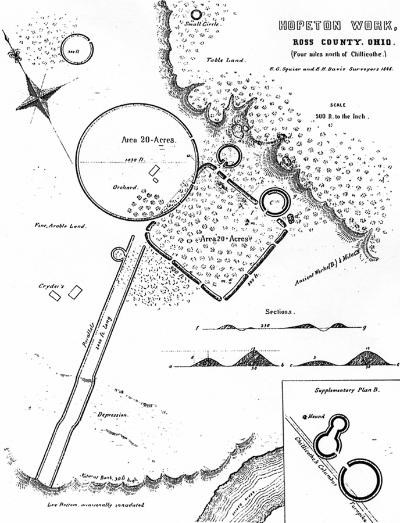

The Hopewell Mound Site could be described as a parallelogram, measuring 900 feet by 950 feet, one big circle measuring 1,050 feet in diameter, and two smaller circles of land measuring 200 and 250 feet in diameter. The wall around the parallelogram was 12 feet tall and 50 feet wide at the base. As for the circles, their walls were 5 feet high. These measurements were taken in 1848 from the remnants of the site, four miles north of Chillicothe, OH (“Archeology at Hopewell”, n.d.). Several mounds remain at the Hopewell Earthwork preserved and kept safe by its designation as a World Heritage Site (“Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks” n.d.). However, no remnants of the walls remain on the Chillicothe land, and in the time that funds were being acquired to purchase the land by the National park Service (10 years), due to annual cultivation and the rising popularity of high-powered tractors, the mounds began to downsize (“Archeology at Hopewell”, n.n.). Over time, the walls were left to ruin too.

Undermining the theory of defense and aversion to foreigners are the artifacts found in the Hopewell burial mounds and around the site. Most notably, were the remnants of obsidian found in the region, all traced back to Yellowstone in Wyoming (“Hopewell Culture Obsidian”, n.d.). Other artifacts found in the Scotio River Valley and the Hopewell Earthworks, were fossilized shark teeth from the Gulf Coast, jewelry made from copper and silver of the Great Lakes, and mica from the Appalachian Mountains (Langdon, n.d.). However, there was little evidence of obsidian, specifically, as one travels from Wyoming to Chillicothe, indicating that the obtainment of these materials was not through trade (Langdon, n.d.). Archaeologists believe Hopewell Earthworks to be a cultural and ritualistic center that brought people of other tribes, other cultures, and other regions on a pilgrimage-like journey similar to that which many made to Cahokia of the Mississippi (Langdon, n.d.). Thus, these walls were not created to keep people away from mounds, the presence of gates and breaks like a welcome message. The presence of foreign artifacts found buried in these mounds represents a sense of respect the Hopewell people had for those who found solace in the ritualistic center it was and for what they could provide.

References

“Archeology at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (U.S.” 2020. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/archeology-at-hopewell-culture-national-historical-park.htm.

Blank, John. 2003. “Document – Mound City: Aerial View.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/193118.

“Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks – Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (U.S.” n.d. National Park Service. Accessed November 12, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/hocu/learn/historyculture/hopewell-ceremonial-earthworks.htm.

“Hopewell Culture Obsidian (U.S.” 2022. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/hopewell-culture-obsidian.htm?utm_source=article&utm_medium=website&utm_campaign=experience_more&utm_content=large.

“Hopewell Mound Group – Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (U.S.” 2023. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/hocu/learn/historyculture/hopewell-mound-group.htm.

Langdon, W. n.d. “Intriguing Interactions.” National Geographic Society. Accessed November 12, 2023. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/intriguing-interactions/.

“Who Were the Hopewell?” n.d. Archaeology Magazine Archive. Accessed November 12, 2023. https://archive.archaeology.org/online/features/hopewell/who_were_hopewell.html.

Bibliography

http://worldheritageohio.org/hopewell-ceremonial-earthworks/