Until the 1970’s, Paleolithic art was classified into two major groups: parietal art, including cave and rock art, and portable art. The clear difference between the two is that one form is moveable and the other is not. This classification gave rise to a bias in understanding and interpreting Paleolithic art, especially when considering portable and nonfigurative representations.

Many archaeologists derived working concepts of art from art historians when looking at style, perspective and form. However, the bias that arose from this method came as a result of art theory ideals prevalent since the Renaissance. There was an emphasis and focus on the “naturalistic” ideal in which artists were praised for their accuracy in representing the world. These guidelines then put great importance on cave paintings, which had more “realistic” art representations, and often underestimated or ignored portable artifacts and ornaments.

To further this bias, 18th century Europe saw the growth of public art museums, such as The British Museum and the Spanish Royal Museum of Painting and Sculpture. With this new appreciation for aesthetics, crafts were pushed aside and judged as mechanical and unrefined. During this period, the parietal/portable classification of Paleolithic art, which already rejected portable work for its lack of naturalism, started to adapt to the fine arts/crafts distinction in which portable art was seen as naïve or infantile. At this time, some archaeologists assumed that painting was an indicator of higher cognitive function as compared to the skills in making portable pieces.

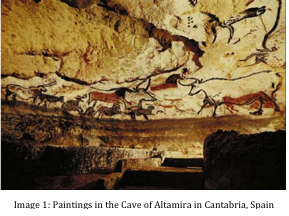

What is clear is that if art theorists were captivated by paintings yet denigrated crafts, archeologists followed suit, ignoring many portable works while celebrating cave paintings, such as those at Altamira and Niaux.

Many culminating factors, such as the globalization of Paleolithic art studies and the development of new approaches to art and symbolism, led to a change in archaeologists’ viewpoints in 1970. These new methods took into account that the making of artifacts was the culmination of the artistic experience. To understand the value of the piece, the creator’s stance toward a work of art must be considered. Furthermore, portable art and personal objects, while previously ignored, were now recognized for their value in assessing the social culture of Paleolithic groups. While parietal images on a wall might serve as landscape markers, portable objects are now regarded as indicators of social and individual identities. Since portable objects have the potential of traveling distances, it is acknowledged that these artifacts and art pieces could have been used to express the social statuses of individuals or groups within a larger Paleolithic culture.

Overall, social stigma derived from art theorists and artistic culture previous to 1970 influenced archaeologists interpretations of Paleolithic art in such a way that cave paintings were generally overemphasized relative to portable art pieces. However, with the rejection of this Eurocentrism and an anthropological turn in the conceptualization of Paleolithic art, movable and fixed forms of art are now considered distinct yet equal in their insight into different aspects of Paleolithic culture.

Works Cited:

Renfrew, Colin, and Paul G. Bahn. Archaeology Essentials: Theories, Methods, and Practice. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson, 2010. Print.

Moro Abadía, Ór 2013, ‘Paleolithic art cultural history’, Journal Of Archaeological Research, 21, 3, pp. 269-306, Anthropology Plus, EBSCOhost, viewed 27 September 2014.

Image 1: http://www.thehistoryhub.com/cave-of-altamira-facts-pictures.htm

Image 2:http://ns1.wynja.com/hohlefelsvenus.html

Additional Reading:

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10816-010-9085-9/fulltext.html

http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/3630753.pdf?acceptTC=true&jpdConfirm=true