With undeniable evidence that proved that Native Americans, too, built great civilizations – achieving amazing architectural feats and forming complex societies with centralized governments – Cahokia challenged people’s preconceptions of ancient Native Americans. Contrary to popular belief, Native Americans also dealt with overpopulation and overexploitation of their natural resources. With such a massive population, which boomed around 1050 AD, Cahokia needed to produce much more food than they had before. Thanks to modern technology and advancements in archaeology, such as water flotation techniques, archaeologists are able to get better insight into Cahokia’s food production and Cahokian diet.

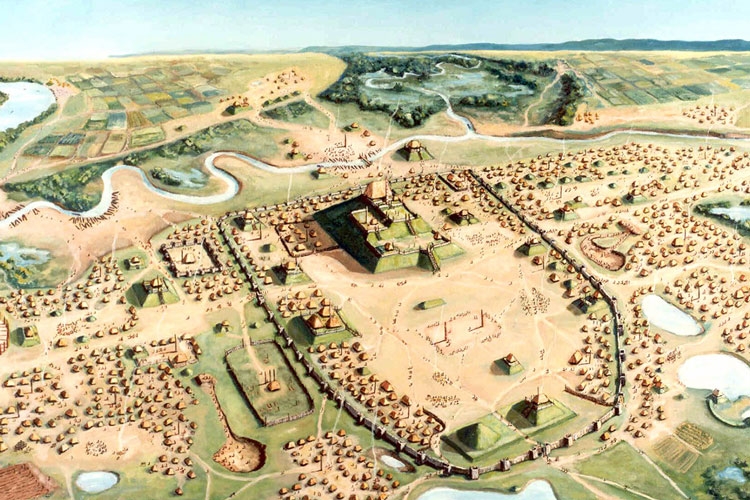

Cahokia was a highly centralized society conveniently placed in very fertile farmland (Figure 1); around the great urban center, farmers worked hard to feed the demanding population (Seppa, 1997). Cahokian rulers deliberately established the upland and bottomland farming villages. Having both upland and bottomland farming environments proved vital in food production, providing a larger variety of food and enhancing the security of food supply; if one area failed, Cahokians still had another area to draw resources from. For instance, if the bottom fields flooded, the upland fields would still thrive. On the other hand, if there was not enough rain one year, the upland fields would be too dry to sustain crops, but the bottom fields would still hold enough moisture to succeed (Tainter, 2019).

Before the rise of Cahokia, people depended primarily on diverse plant foods and consumed animals in lesser amounts. However, as the population grew, their dependence on certain foods changed. Fish, which used to be a staple food, went from 77% to 10% in consumption. Mammals, on the other hand, went from 10% to 67% in consumption, which is indicated by the increase in deer remains. The most significant staple food for the Cahokians was maize; originally domesticated in Mexico, it made its way up to the American Southwest where it became more than just a staple food – but a religiously significant crop (Tainter, 2019). Cahokians also shifted from horticulture to mass-producing agriculture. They cultivated goosefoot, amaranth, canary grass, and starchy seeds; they were able to mass produce these by storing seeds in communal granaries (Figure 2), which were uncovered during excavations (Seppa, 1997).

The end of Cahokia still remains a great mystery, but it seemed to occur around the time when descendants of the upland farmers left their farms in 1150 AD, throwing Cahokia’s government and economy into turmoil (Pauketat, 2009). This goes to show how farmers were the foundation of this grand civilization. As we covered in class, the Cahokians aimed to produce the maximum to survive, which is ultimately unsustainable and is the reason for their end. This parallels overconsumption today, which is one of the biggest problems of society today. We should take our knowledge of this ancient civilization as a warning to what could happen if we continue to overexploit our resources and mass-produce.

References:

Anwar, Yasmine. January 27, 2020. “New Study Debunks Myth of Cahokia’s Native American Lost Civilization.” Berkeley News. https://news.berkeley.edu/2020/01/27/new-study-debunks-myth-of-cahokias-native-american-lost-civilization.

Everding, Gerry. March 21, 2019. “Women Shaped Cuisine, Culture of Ancient Cahokia.” The Source.https://source.wustl.edu/2019/03/feedingcahokia/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CIt%27s%20clear%20that%20the%20vast,the%20society%2C%E2%80%9D%20she%20said.

Pauketat, Timothy R. 2009. “Digging for the Goddess.” In Cahokia: Ancient America’s Great City on the Mississippi. pp. 123-128. Penguin Group: Viking Penguin.

Seppa, Nathan. March 12, 1997. “Metropolitan Life on the Mississippi.” The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/daily/march/12/cahokia.htm#:~:text=As%20a%20corn%2Dbased%20economy,grass%20and%20other%20starchy%20seeds.

Tainter, Joseph A. December 3, 2019. “Cahokia: Urbanization, Metabolism, and Collapse.” Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2019.00006/full.

Tumblr. “Mike Ruggeri’s Ancient Cahokia.” n.d. https://mikeruggerisancientcahokla.tumblr.com/

Further Reading:

Chen, Angus. February 10, 2017. “1,000 Years Ago, Corn Made This Society Big. Then, A Changing Climate Destroyed It.” npr. https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/02/10/513963490/1-000-years-ago-corn-made-this-society-big-then-a-changing-climate-destroyed-the.

Fritz, Gayle J. Feeding Cahokia: Early Agriculture in the North American Heartland. The University of Alabama Press, 2019.

Knox, Pam. March 30, 2019. “How did Cahokian farmers feed such a large city?” UGA Cooperative Extension. https://site.extension.uga.edu/climate/2019/03/how-did-cahokian-farmers-feed-such-a-large-city/.