Medical archaeology is a relatively new subfield that analyzes materiality such as surgical tools, human bones, and ancient DNA to study the history of healthcare and medicine. Archaeology proposes engaging questions about medicine and health in relationship to artifacts, features, and structures. Medical archaeology also bridges the gaps in knowledge found in textual formats such as medical history. As an anthropology major and pre-med student, I was delighted to examine medicine through an archaeological lens. Overall, this research was a fun break from wrapping my head around organic chemistry concepts.

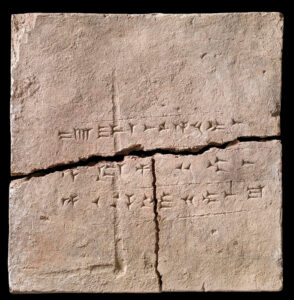

There are many archaeological finds relating to ancient medicine and health. For example, a 7th-century BC female skull excavated at Thrace shows definitive evidence of cranial surgery. The skull revealed scraping of cranial bone in width, length, and depth. Meanwhile, in Egypt, the Ebers papyrus details physicians’ medical practices. The papyrus suggests the use of Tar in healing skin conditions and rashes. Additionally, the papyrus notes the use of cannabis for healing fingernails. These archaeological finds suggest advanced healing practices and surgery during antiquity.

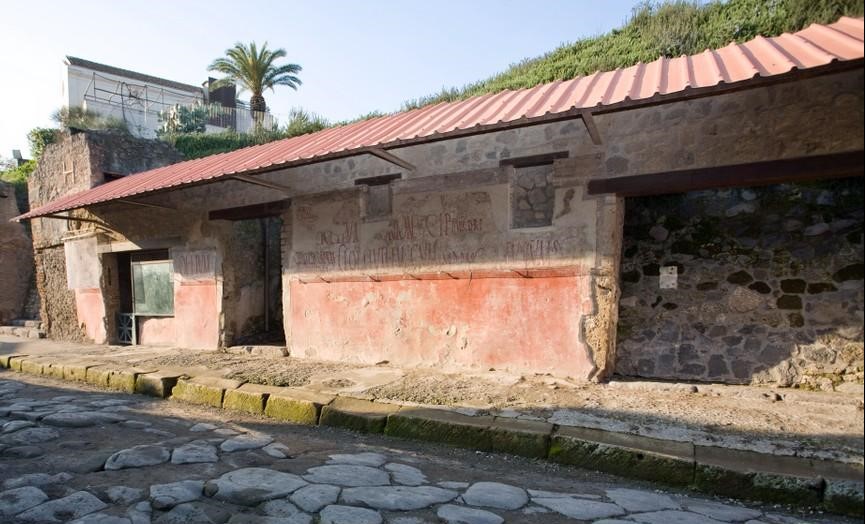

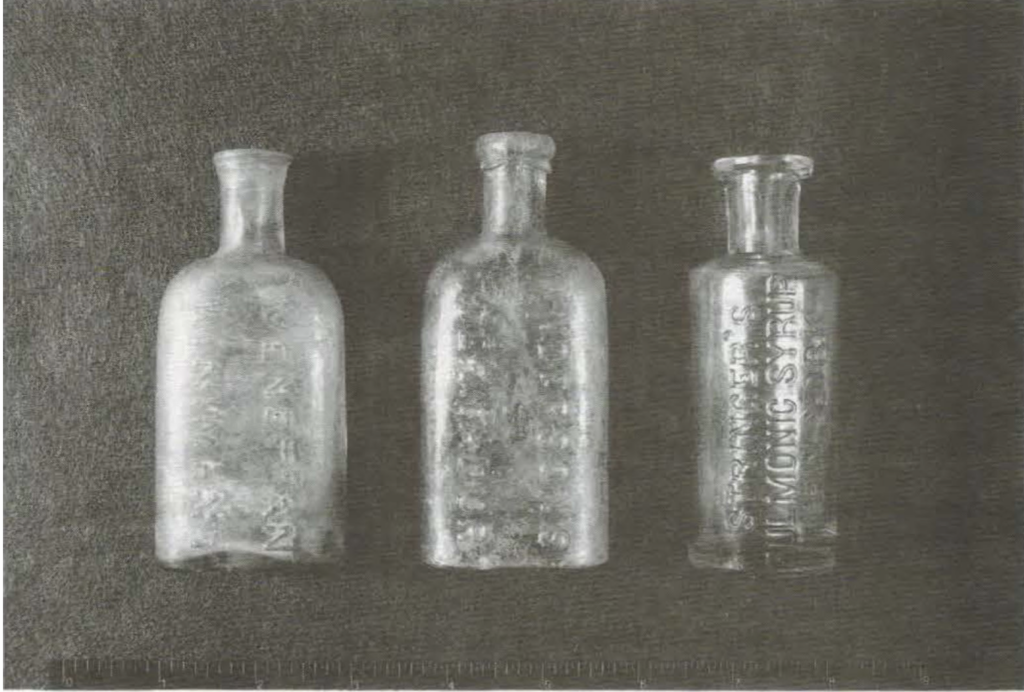

A more modern example of medical archaeology is The Archaeology of 19th Century Health and Hygiene at the Sullivan Street Site In New York City. The site focuses on backyard features and artifacts from four house lots. During the 19th century, medicine was the primary medical treatment for illness. Types of treatment available were home remedies, prescribed medicines, and over-the-counter patent medicines. Patent medicines were more affordable than prescription medicines.

Some Sullivan Street households were Dr. Robson and a lower-class family at 93 Amity Street. Dr. Robson’s assemblage included only medical bottles. Meanwhile, 93 Amity Street only contained patent bottles. Hygiene was increasingly becoming a priority and was associated with moral status. Hygiene items such as soap containers, basins, and toothbrushes were discovered at each Sullivan Street residence. Once more, there were more items discovered at Dr. Robson’s than at 93 Amity Street. Therefore, access to prescription medicine and hygiene products was based on class and wealth.

What is archaeological science? Archaeological science is an innovative method of approaching historical health and medical practices with archaeological materials such as skeletal remains and ancient DNA. Skeletal and ancient DNA analysis is used to uncover biological sex, health conditions, and diseases. Iron deficiency, known as anemia, is detected in small holes in the skull and ancient DNA analysis. Interestingly, Ancient DNA has been discovered on objects such as a Paleolithic pendant and in sediment from Pleistocene caves. Overall, Extracting ancient DNA is challenging and easily degraded with modern DNA. Archaeological science is so fascinating because it carries archaeology into the future of scientific research and analysis.

Additional Reading

https://medicalmuseum.health.mil

https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/journal-of-archaeological-science

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8178570/

Bibliography

Baker, Patricia Anne 2016Chapter 1, Chapter 7. Essay. In The Archaeology of Medicine in the Greco-Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Diamandopoulos, Demetrios 2014Medicine and Archaeology. Essay. In Medicine and Healing in the Ancient Mediterranean. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Howson, Jean E. 1993The Archaeology of 19th-Century Health and Hygiene at the Sullivan Street Site, New York City. Northeast Historical Archaeology 22(1): 137–160.

Ludlow, Hannah 2020Ancient Skin and Haircare. Project Archaeology. https://projectarchaeology.org/2020/04/17/ancient-skin-and-haircare/, accessed September 9, 2023.

Massilani, Diyendo, Mike W. Morley, Susan M. Mentzer, et al. 2021Microstratigraphic Preservation of Ancient Faunal and Hominin DNA in Pleistocene Cave Sediments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119(1).

Saraceni, Jessica Esther N.d.Woman’s DNA Recovered from Prehistoric Pendant. Archaeology Magazine. https://www.archaeology.org/news/11417-230504-denisova-pendant-dna, accessed September 9, 2023.

Image Credit

Image 1 Google

Image 2 Howson

Image 3 Martin Rowson