The adage goes that if we do not learn from our past than we are bound to repeat it. Nowhere is this clearer than when we look at the fall of the Roman Empire and the social and financial situations prior. Before the collapse of the Roman Empire, the top 1% of its population controlled over 16% of its wealth. The Gini coefficient; which measures the level of income disparity in a society where 0 is perfectly equal and 1 is perfectly unequal, measured Rome at an incredibly high 0.43[1].

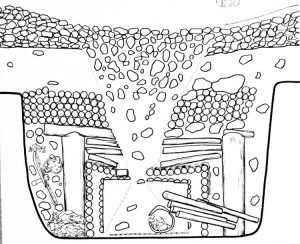

Further compounding the issue was that wealthy Romans increasingly removed themselves from cities and positions of power as they saw the first signs of collapse from the edges of the empire. This is made very clear in the archaeological record where before the end of the Roman Empire there was a large spike in fortified villas far from cities and people[2].“Their disinclination to lead may have been caused by forced exactions, confiscations, business concerns, tax pressured, or general economic fears, which made protecting one’s own interests seem more prudent than looking out for the interests of others.”[3] In their selfishness the upper class romans abandoned their people when they needed them most, only further destabilizing Rome.

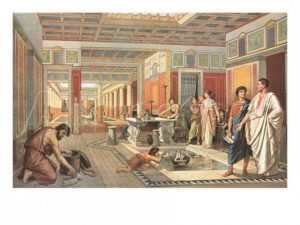

Worsening matters was the fact that Rome had been built on expansion, militarism, and the spoils of war. “Being Roman eventually meant being whatever wealth said it was, and shorn of the old ties that kept the rich and poor together out of a mutual sense of common destiny, they soon turned on one another.”[4] Soldiers and common citizens could no longer trust that they would get what was “theirs” as the ruling upper-class tended to keep all of their wealth to themselves while maintaining slaves who did all of the work of the typical middle working class. All that was left for citizens and soldiers was economic squalor as wealth continued to be inherited by the rich, and labor was taken by the slaves of war.

These are just a couple reasons for the fall of Rome, but what is perhaps most terrifying about the fall are the corollaries to today. The Unites States of America has a Gini coefficient of .45, and 40% of the wealth is controlled by the top 1% of the population.[5] By every metric, the United States is even more divided and unfair than Rome before its fall. The effects are perfectly evident as well as there is increasing inclination from the rich to build fallout bunkers and withdraw from civilization and politics just as the roman elites did centuries before. Worsening matters is the evidence of extreme racism towards migrant workers who like slaves in Rome “take the labor from the hardworking middle class”. Increasingly the middle class shrinks as social unrest and bigotry grows. It is a scary combination that, if we aren’t careful, could spell the end of civilization as we know it, just like it did for the Romans centuries before.

Bonus:

Sources:

[1] http://www.businessinsider.com/even-the-roman-empire-wasnt-as-unequal-as-america-today-2011-12

[3] Ermatinger, James William. The decline and fall of the Roman Empire. Greenwood Press, 2004, Page 58.

[5] http://www.businessinsider.com/even-the-roman-empire-wasnt-as-unequal-as-america-today-2011-12

Picture Sources:

Diocletian’s Palace, Croatia. This heavily fortified palace was built at the turn of the 4th century for Roman emperor Diocletian. The massive palace was protected by large walls with numerous towers. Some times, it housed over 9000 people. I’ll post more in the comments. from castles

https://popularresistance.org/the-science-of-inequality/

Reading Thomas Piketty: A Critical Essay

Further Reading:

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2015-09-30/following-ancient-romes-footsteps-moral-decay-rising-wealth-inequality