The Life and Song of a Mourning Warbler (Geothlypis Philadelphia)

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order:Passeriformes

Family: Parulidae

Genus: Geothlypis

Species: Geothlypis philadelphia

“Mourning Warbler”

“Mourning Warbler.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 22 Nov. 2017,

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mourning_warbler.

Physical Appearance:

Mourning warblers are 10-15cm in length and are a dimorphic species meaning that the males look very similar to the females. Their underbellies and wings are an olive green color, but the underbelly has a more yellow tint in comparison to the wings. They have a gray hood that starts at the crown and goes down to the breast. A darker gray band in between their eyes gives them spectacles. Although the males and females look very similar, a way to tell the difference is that the female has a lighter gray hood and the male has more dark gray and black coloring at the top of its breast.

Staff, BSBO Research. “Warbler Species Beginning to Increase.” BSBO Bird Bander’s Blog, 1 Jan.

1970, bsbobirdbander.blogspot.com/2013/09/warbler-species-beginning-to-increase.html.

Their Social System:

Mourning warblers (Geothlypis philadelphia) live in territories that average about 2 acres of area. The territory is typically defended by a small number of adults males that use a territorial song as the main defense. In close contact with a rival male, they will bob up and down rapidly, flapping wings and tails and sing frequent short tschrip notes. Similar aggressive behavior is also observed between females, especially those with young nesting. Both the males and females take care of the young which leave the nest after 8-9 days after hatching. Families remain in close contact for about three weeks after the young leave the nest at which point the fledglings become more independent and forage on their own, but still have some contact with adults.

The Birds of North America (P. Rodewald, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology; Retrieved

from The Birds of North America: https://birdsna.org; OCT 2017.

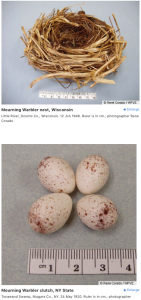

Their Breeding Behavior:

Information on specific sexual behavior is not well documented. Males sing to defend their nesting territory, they bob around and spread wings and fan tail or give chase. These behaviors have been observed both within the species and among mourning warblers, yellowthroats, and ovenbirds. These birds begin courtship as soon as they arrive at the breeding grounds around late May and early June. The nests tend to be partially hidden in dense shrubbery or grass, but they have a brood parasitism rate that can get as high as ten percent. This may happen so frequently because of logging and loss of dense habitat in which to conceal nests, but research on the subject is minimal. The incubation period for a mourning warbler is about 12 days. The father is involved and feeds the mother during the incubation period. The mother eats the egg shells after the fledglings hatch. After incubation, the mother is highly attentive to her young as a whole but most attentive in the early morning and at night. The nestling period lasts about 9 days and both the adult male and female feed the young in the nest.

“Mourning Warbler.” Audubon, 1 Mar. 2016, www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/mourning-warbler.

The Birds of North America (P. Rodewald, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology; Retrieved

from The Birds of North America: https://birdsna.org; OCT 2017.

Their habitat of choice:

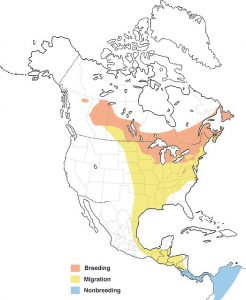

During the breeding season, mourning warblers tend to live in clearings, thickets, undergrowth. During the migration season, this information not well documented, but they have been observed observed in mixed forests of black cherry, red maple, and white oak. During the winter, they live in the tropics in thickets and overgrown fields in the foothills and lowlands.

The Birds of North America (P. Rodewald, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology; Retrieved

from The Birds of North America: https://birdsna.org; OCT 2017.

“Can’t See the Thicket for the Trees.” Collecting Tokens, 10 Oct. 2014,

collectingtokens.wordpress.com/2014/10/10/cant-see-the-thicket-for-the-trees/.

Division of Forests and Lands,

Albany Thicket Biome, pza.sanbi.org/vegetation/albany-thicket-biome.

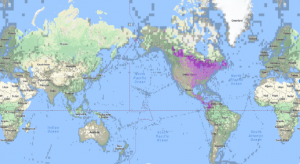

Migration:

Mourning warblers leave the U.S. and Canada most commonly in late August, but as late as early November. In the spring, they migrate back toward the U.S. through Central America and through Mexico into the southern states. Researchers have investigated the effects of global warming on the spring migration of birds in general and found that they return earlier in warmer years and later in colder years, but there are conflicting results about the exact dates of migration changes.

The Birds of North America (P. Rodewald, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology; Retrieved

from The Birds of North America: https://birdsna.org; OCT 2017.

Their Foraging Behavior:

Typically forages alone in shrubs a few feet off the ground, sometimes pursuing insects. They mainly eat beetles, spiders, insect larvae, and fruit. The majority of individuals observed traveled along low branches, flying for no longer than 1 meter at a time. The most actively forage during dawn and dusk (diurnally). When they consume an insect, they catch it with the beak, pick off the arms and legs and discard them then consume the rest of the insect whole. When they eat fruit, they tend to peck at it while it still hangs from the branch. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDMNtG051CY

Yoramjg. “Mourning Warbler Feeding.” YouTube, YouTube, 27 May 2016,

www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDMNtG051CY.

Cox, G.W. 1958. A Life History Study of the Mourning Warbler.

The Birds of North America (P. Rodewald, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology; Retrieved

from The Birds of North America: https://birdsna.org; OCT 2017.

Observations that you have made of the birds on Vassar’s Campus or in Dutchess County:

None.

Media Concerning the Biology:

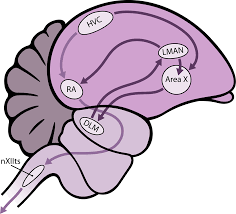

“How Birds Sing.” Bird Academy • The Cornell Lab, 17 May 2016,

academy.allaboutbirds.org/how-birds-sing/.

Nottebohm, Fernando. “The Neural Basis of Birdsong.” PLOS Biology, Public Library of Science,

journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pbio.0030164.

Where Should research on This Bird Be Concentrated:

Research should be concentrated on why mourning warblers have such a high occurrence of brood parasitism because although there is a standing hypothesis as to why there is not much research to support this hypothesis. Research should also be done to track the full migration cycle of the mourning warbler to gather more information about its preferred habitats during migration.

Cool Article We Found:

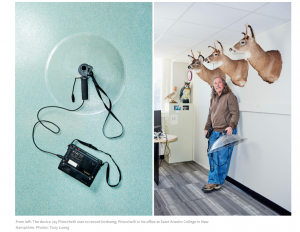

As further explained in the blog post dedicated to the mourning warbler’s song, mourning warblers are regiolect songbirds which means that each regional population has a distinct dialect. A mourning warbler sings the same song over a range of up to hundreds of miles but in the face of a barrier such as a mountain range or lake, the dialect changes. Understanding this concept, Jay Pitocchelli sought out to track the migration path of the mourning warbler through a method of crowdsourcing birdsong. He asked birders across the Americas to record the mourning warbler’s song April through May and when he retrieved this data, he notes the dialect and the region that the song came from and is attempting to piece these together into a traceable map. The questions he aims to answer through this study are “Does it look like there’s the potential for a new species to evolve within this Mourning Warbler breeding range?” and “Are they migrating together, or are they separating from other populations?”

“This Guy Is Mapping How Warblers Migrate, Just by Listening to Them Sing.” Audubon, 20 Sept. 2017, www.audubon.org/magazine/spring-2017/this-guy-mapping-how-warblers-migrate-just.

How would we conduct a study

In order to test the hypothesis that brood parasitism occurs at a high rate within nests of mourning warblers due to loss of habitat, we could identify territories in which there is a large loss of habitat and territories in which the habitat is ideal and compare the rates of brood parasitism between the groups. If there is a statistically significant difference in the rates of brood parasitism in between the groups, this observation would support the hypothesis. If there is not a statistically significant difference, we could then look for other factors that differentiate areas of the mourning warbler that have high rates and areas that have low rates, or if the rates are very similar across the board, factors that differentiate mourning warblers from birds with very low rates of brood parasitism. Conducting a study that physically follows the mourning warbler along its migration path would be time-consuming and costly, so performing replication studies similar to the study being conducted by Jay Pitocchelli would be practical and produce valuable data on the migration path of mourning warblers at a lower cost.

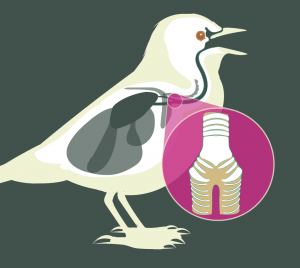

Singing Behavior :

For song vocalization in the Mourning Warblers, only the males sing.The primary male song sounds like “churry churry churry churry chorry chorry”. The male mourning warbler has a flight song that occurs when it is ascending in flight and ends when a certain height is reached. Both males and females commonly produce two calls, one a loud and harsh tshrip and the other a higher pitch less harsh tsip. Tshrip is commonly heard during male territorial defense and by both males and females when disturbed away from the nest area as well as during migration. The softer note is more often heard when fledglings are approached and between two females during a territorial encounter. According to Pitocchelli’s study on the Macrogeographic variation in the song of the Mourning Warbler, each regional population has a distinct dialect as regiolect (regional dialect) is formed when all individuals from several populations share a common song type.

Image of the primary song of Mourning Warbler:

“Mourning Warbler Song Spectrogram”

Further Research:

More effort should be put into researching how fledgling mourning warblers develop song in a social context. There is a lot of data and description on what mourning warblers sing, but few if any accounts on what system is specific to fledgling mourning warblers in how they learn.

Method of Further Research (How would we conduct a study):

We would conduct an observational study to amass enough qualitative data to make an inference about how mourning warblers learn. This could occur in many different ways, so it would be best to target the experiment toward deciphering whether or not mourning warblers use social eavesdropping as a method of learning. In our hypothesis, we would assume that they do utilize social eavesdropping. Hypothesis: Mourning warblers use social eavesdropping as a method through which fledglings can develop the song. We would then mark off an entire mourning warbler territory and tag the babies from several nests within the territory. Once they left the nest about a week later, we would collect data on the number of time fledglings spent in the presence of vocalizing adults and in what context (was it territorial singing? Did the fledgling attempt to respond? How successful is the fledging song at this moment in time?) We could then see if there is a relationship between interaction with vocalizing adults and progression and quality of a fledgling’s song. If there was a relationship, we would not reject our initial hypothesis. If there was no relationship, we would reject our initial hypothesis. In either case, more research and evidence would be required. We could also conduct an experiment in which we raise baby warblers in a lab setting, one group with a tutor and one group without. This could tell us whether or not mourning warblers sing innately. If the group without a tutor/any direction is able to sing a complete mourning warbler song, the song is innate. If the group without direction cannot sing the correct song, the song is learned.

Works Cited

“This Guy Is Mapping How Warblers Migrate, Just by Listening to Them Sing.” Audubon, 20 Sept.

2017, www.audubon.org/magazine/spring-2017/this-guy-mapping-how-warblers-migrate-just.

Nottebohm, Fernando. “The Neural Basis of Birdsong.” PLOS Biology, Public Library of Science,

journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pbio.0030164.

Cox, G.W. 1958. A Life History Study of the Mourning Warbler.

The Birds of North America (P. Rodewald, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology; Retrieved

from The Birds of North America: https://birdsna.org; OCT 2017.

“How Birds Sing.” Bird Academy • The Cornell Lab, 17 May 2016,

academy.allaboutbirds.org/how-birds-sing/.

Staff, BSBO Research. “Warbler Species Beginning to Increase.” BSBO Bird Bander’s Blog, 1 Jan.

1970, bsbobirdbander.blogspot.com/2013/09/warbler-species-beginning-to-increase.html.

“Mourning Warbler.” Cornell Lab of Ornithology, www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Mourning_Warbler/id

“Mourning Warbler.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 22 Nov. 2017,

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mourning_warbler.

“Mourning Warbler.” Audubon, 1 Mar. 2016, www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/mourning-warbler.

Yoramjg. “Mourning Warbler Feeding.” YouTube, YouTube, 27 May 2016,

www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDMNtG051CY.

“Can’t See the Thicket for the Trees.” Collecting Tokens, 10 Oct. 2014,

collectingtokens.wordpress.com/2014/10/10/cant-see-the-thicket-for-the-trees/.

Division of Forests and Lands,

Albany Thicket Biome, pza.sanbi.org/vegetation/albany-thicket-biome.

“Field Guide to Birds of North America.” Whatbird.com,

identify.whatbird.com/obj/340/_/Mourning_Warbler.aspx.

Blog Post 2:

Cox, G W. 1958. A Life History Study of the Mourning Warbler.

The Birds of North America (P. Rodewald, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology;

Retrieved from The Birds of North America.

Pitocchelli, J. 2011. Macrogeographic variation in the song of the Mourning Warbler (Oporornis

philadelphia). Zoology 11: 1027-1040.

Pitocchelli, J. 2011. Mourning Warbler (Geothlypis Philadelphia), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (P. G. Rodewald, editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA.

Mourning Warblers are rare but regular migrants in Northeastern Montana. It was one of the few rather rare but regular warblers I was able to find so far this spring. It is even more unusual to have one hang out for this long.