How predator and prey species interact with each other can affect the dynamics of an ecosystem and the consequent species composition and diversity of the area. Because of this, piecing together how these interactions occur and on what levels is of great interest to scientists around the globe. In this paper, a field experiment was performed to test whether insectivorous bird species, such as the great and blue tits, can detect the chemical cues (or pheromones) of their prey during mating season in order to locate them. In general, chemical cues are often used for sexual selection and mate choice. For female winter moths, which were the primary prey species used in this experiment, pheromones are released during their mating season. Male moths detect these chemical signals and make haste to find the females location and commence the mating process. However, releasing these pheromones is costly and uses energy. Not only is the female giving up her location to potential mates, but she is also giving up her location to predators and parasites who may be eavesdropping on her pheromone signals. This indicates a trade-off between increasing fecundity through chemical signaling while facing the risk of increased predation and parasitism. Previously, birds’ ability to detect chemical cues has not been studied as they were thought to be anosmic (lacking sense of smell). However, recent studies show otherwise, proving that birds can detect odors in multiple ecological contexts such as kin recognition, orientation, navigation, and for foraging. That said, studies have yet to explore whether insectivorous birds can eavesdrop on their preys’ chemical signals in order to locate them. Fortunately, that is what this research study is all about.

Located in the Pyrenean Oak forest in Spain, this study took place over 27 days between May and June of 2016. Within the study site, 100 wooden nest-boxes house a large population of breeding birds, in particular 45 pairs of blue tits and 10 pairs of great tits. These two bird species were the focus of this experiment as they feed mainly on winter moth caterpillars during their mating season and on adults during the winter.

Blue tit species Great tit species Winter moth species

In order to measure whether these birds could detect the pheromones released by the winter moths, synthetic pheromone dispensers and control dispensers (no pheromones) were randomly placed in Pyrenean oak tree branches 10 meters away from the various nest-boxes. One dispenser, either the control dispenser or the commercial pheromone dispenser, was placed in each tree with 10 surrounding artificial winter moth larvae made of light green plasticine that resembled the natural color of the moths. To measure predation levels, the number of larvae with predation marks by birds in the trees was recorded and one predation event was marked by at least one artificial larvae with observable bird damage. Artificial caterpillars with visible damage were replaced with new ones at every check point. Because the synthetic pheromone dispensers lasted for 40 days, each site was checked every two days for the first 10 days and then checked twice on days 20 and 27.

Pheromone dispenser (pink) and several plasticine caterpillars (green), one with observed beak damage from a bird.

Pheromone dispenser (pink) and several plasticine caterpillars (green), one with observed beak damage from a bird.

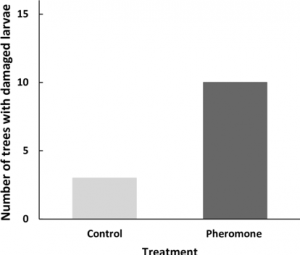

The results of this study found that a greater number of artificial larvae were preyed upon by insectivorous birds when the tree contained the winter moth pheromone dispenser compared to trees with the control dispenser.

Ten out of the sixteen trees with the pheromone dispenser had observed predation events while only three out of the sixteen trees with the control dispenser had observed predation events.

These results indicate that insectivorous birds, namely blue tits and great tits, can detect sex pheromones released from winter moths in order to determine prey location, maximizing their foraging efforts! These findings match the experiment’s hypotheses that if the birds could detect prey pheromones, then there would be higher levels of predation on the artificial larvae placed in trees with the pheromone dispenser. In order to decrease the number of confounding variables, the study took place during the spring when adult winter moths were absent. Furthermore, the pheromone dispensers were placed in an insect trap prior to the study in order to test whether other insects were attracted to the same pheromones. No other moths or arthropods were observed.

Overall, the fact that insectivorous birds can use their olfactory senses to detect their preys’ chemical cues during mating season is fascinating and has both species-specific and ecosystem implications. For the winter moth species, the ability of birds to locate their mating chemical cues indicates that releasing those pheromones is costly for the female moths and for the responding male moths. Furthermore, these results indicate that insectivorous birds may play a vital role in controlling insect and caterpillar populations in forest ecosystems, decreasing the amount of herbivory and parasitism in tree species. This knowledge could be applied when dealing with biological controls for invasive species.