Have you ever asked a friend, “What you want to eat for lunch?” and they replied saying “I heard this place was really good, we should go here!” ?Using the friend’s information about certain restaurants, you are more likely to find a high quality meal with your friends than searching many restaurant alone. Finding a nutritious meal is a high priority for not only humans, but also for the the greater mouse-tailed bat, Rhinopoma microphyllum. Surprisingly, these bats like to use information from their peers in finding food, just like us.

The greater mouse-tailed bat stays in colonies of hundreds or thousands of individuals and forages in groups. Using a very high frequency, these bats use echolocation to detect their prey.

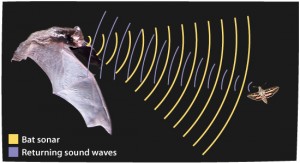

Echolocation is the use of sound waves and echoes to locate and determine objects in space as seen in the figure above. After a bat sends out its sound waves from its mouth or nose, it listens for the echoes that informs the bat about the location, size, and shape of the object.

For example, here is a bat using a standard repeated call for basic navigation. The faster clicking in the sound clip is most likely the detection of an insect, yet more information would be needed for the bat to catch it’s prey. This is where social foraging may play a key role in the bat’s ability to find food.

Intrigued by the idea of social foraging, Cvikel et al. 2015 studied why the R. microphyllum chooses to forage an area in high densities. They found that the bats actively group together and choose to forage as a unit rather than alone. This is because the echolocation of their peers allows the bats to eavesdrop on each other about the location of their prey. By offering public information to one another, this allows the bats to effectively operate as a collection of sensors. This is like how humans gather information about good restaurants and share it publicly on review sites such as Yelp. In addition, social foraging was even more beneficial because their prey, the Camponotus queen ants, lived in colonies and were located in batches.

However when a very high density of bats aggregate, it formulates a huge problem. Surprisingly, the bats aren’t necessarily competing with one another for the food, but rather the resources of their echolocation sensors are being focused on detecting their peers and not their prey. Seeing this, Cvikel et al. proposes the following trade off where aggregation improves foraging but when the density of bats became too high, sensory resources had to be relocated to the other bats at the cost of losing prey detection.

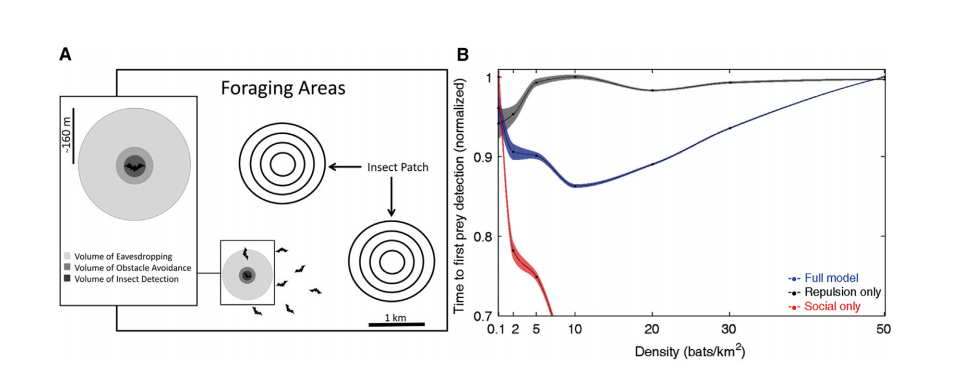

Here the bats sensory range is shown on the far left and how bats must scan the area for the insect patches which is their food. The bats can locate from as far as 10 meters while they stay at least 20 meters away from each other to prevent overlapping their echolocation. The figure on the right represents Cvikel’s proposed trade-off model where basically the bat’s efficiency in finding food decreases as the bat’s density becomes too high (the blue line and the black line). Once the density of bats becomes too high, some of them leave the search party for the better of the group and themselves. Lastly, the red line shows when the bats were able to eavesdrop off one another for the location of the food but their sound waves did not repel each other. This is where we saw the advantage of social foraging; the slope drops super fast indicating a faster, efficient time in finding their food.

Interestingly, we humans aren’t the only ones that pick up gossip about where the good food is. Bats seem to do this as well and by doing so, it saves energy because they send out sound waves less frequently in comparison to foraging alone. This is because they spend a larger portion of their resources listening to their peer’s echolocation rather than using the energy to send out their own. You can think of this as you going on a drive in a search for a good restaurant when you could’ve overheard from a friend about a certain location and saved the energy you spent in going around to find some good grub.

Therefore it seems that bats are not as simplistic as the human eye may find them. They may not be the fabled vicious blood-sucking winged beasts we think they are, but rather clever intelligent critters that harness every ounce of information from each other in order to hunt and thrive under the eerie crescent moonlight.

References

-

Cvikel, Noam et al. (2015) Bats Aggregate to Improve Prey Search but Might Be Impaired when Their Density Becomes Too High Current Biology , Volume 25 , Issue 2 , 206 – 211.