Chicks can do pretty amazing things. One of these things includes getting up and walking around within hours after hatching. How do they walk so well right after hatching? A new study in the Journal of Experimental Biology looked at chick embryos for the answer. The researchers knew before their experiment that chick embryos produce repetitive leg movements (RLMs) even before hatching. In a sense, practice makes perfect. The question is, what mechanism connects the pre-hatching RLMs to the post-hatching walking?

This new study looked at proprioception, which is the sensation of muscles acting on the world. It is the sensation of positioning and strength of certain muscles. In the case of these chicks, proprioception refers to the sensation of the leg muscles when walking. The researchers thought that if proprioception influenced chick embryo RLMs, then proprioception would influence chicks’ walking ability after hatching. On that note, the experiment tested whether or not proprioception had an influence on the leg muscles of embryos. The researchers thought that it would. They used electromyography to test this – electrodes (metal needles that can pick up electrical signals) were inserted into specific muscles to measure electrical activity in these muscles.

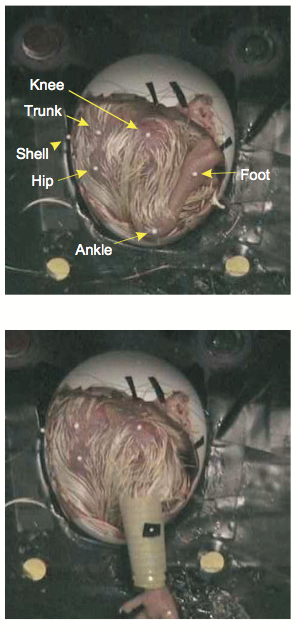

[This image shows the ankle restraint described in the study.]

Differences in proprioception were assessed by placing a restraint on the ankles of these chick embryos. In other words, a chick embryo’s leg was stretched and un-stretched (different proprioception effects) to see the difference in electrical activity in specific muscles. The muscle that they paid closest attention to was the tibialis anterior (TA), which was the ankle muscle being stretched by the restraint. By doing this, the researchers found something incredible. They saw a significant difference in the duration and intensity of the electrical activity in the TA muscle between instances where the muscle was restrained and unrestrained. This means that proprioception was certainly playing a significant role in the repetitive leg movements of these chick embryos.

So, if a chick does not develop the proper proprioception during its time as an embryo, then perhaps the chick will not walk so readily after hatching. In this experiment, however, chicks were not tested after hatching. Only chick embryos were used. More research will need to be done in order to connect proprioception’s influence on muscle activity pre-hatching and post-hatching. Nevertheless, this is a big first step. This study shows the means by which practice makes perfect. Chicks are using proprioceptive information (or the sensation of their own leg muscles) from when they were in the egg to inform their walking ability after they hatch. Basically, chicks are making sure they can walk in the world before they have to actually do it. To find out more, check out the article in the most recent issue of the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Bradley, N. S., Ryu, Y., U., Yeseta, M. C. (2014). Spontaneous locomotor activity in late-stage chicken embryos is modified by stretch of leg muscles. Journal of Experimental Biology, 217, 896-907.