Picture this: you’re in the kitchen shortly after coming home from the hospital with a brand new baby. While you’re chopping tomatoes, someone sneaks into your house with their baby, silently places their baby in the cradle with your own, tiptoes out the back door, yells “Fire!”, and runs away—leaving you in your panicked delirium to return to the house after investigating the fire and, looking on in shock at the bassinet, wonder how in the world you forgot you had had twins.

Common Cuckoo by Mike McKenzie. Wikimedia Commons.

All absurdity aside, this scenario is similar to that which cuckoos—specifically female cuckoos—subject other bird species. Deng et al. examined the oft over-looked and highly important female cuckoo calls. These calls take the form of varying “chuckles” rather than the familiar and unvarying “cu-coo” call of males. “Great,” you’re thinking, “now this parent is laughing at me too on top of leaving me with their kid?” Not quite: a female cuckoo’s “chuckle” is a highly effective imitation of predators, specifically the cries of hawks, that affects both cuckoo hosts and non-hosts alike. Deng et al. hypothesized that these chuckles would change frequently in order to avoid hosts becoming used to any particular distraction call and would change in relation to hawk geographic variation. In a similar vein, cuckoos lay their eggs in host nests and thus need to distract hosts in the afternoon. As a result, Deng et al. predicted that cuckoo calls would be at their peak in the afternoon in order to maximally distract hosts post egg-laying. They also hypothesized calls to be more frequent on days with better weather (i.e., less wind and rain) because sound can travel with less impediment on such days.

Wetland habitat. Liaohe Delta Nature Reserve is known for its striking red grasses, similar to those in this image. Wikimedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2f/GR1270013-sani-nikon2014-05913_stitch-ok.jpg.

In the Liaohe Delta Nature Reserve in Northeast China, one of China’s primary estuarine wetlands, and Wild Duck Lake National Wetland Park, Deng et al. collected field recordings from the common cuckoo, Cuculus canorous, and the Oriental reed warbler, Acrocephalus orientalis, the cuckoo’s most common host this region. Using these field recordings and sound samples from online library Xeno Canto, Deng et al. were able to compare variation within and between male and female groups, and across weather patterns, geography, and times of day.

In this context, Deng et al. broke down the calls of cuckoos into “syllables” and “bouts.” For males, a syllable is a single “cu-coo” sound while a single “kwik” sound is a syllable for females. A bout is a series of successive syllables for both females and males. During the measurement part of the process, the bouts of both male and female cuckoos were measured in terms of how many syllables each contained; their maximum, minimum, and peak frequency; and how long each lasted. Deng et al. defined peak frequency for as that frequency which is associated with the highest sound energy. The study discarded minimum frequency measurements in analysis due to the gradual decreasing energy of female cuckoo calls and the resulting difficulty in finding a standard minimum frequency with which to compare other minimum frequencies.

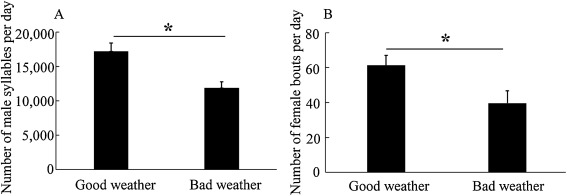

Using measurements of bouts and syllables, Deng et al. found that both male and female cuckoos have higher calling output in good weather than in bad weather, as predicted. Calls are not as effective in bad weather because of how wind and rain physically block sound waves, meaning that it’s much more worthwhile to call more often in good weather when sound will carry more effectively. Also in keeping with predictions, the data shows that male cuckoos have higher consistency in their calls, both within and between male and female groupings. This supports the idea that female cuckoos’ calls change regularly in order to continue fooling hosts. If one female cuckoo’s call sounds different every time, the cuckoo can avoid being recognized and subsequently ignored by the cuckoo’s intended hosts. All in all, good weather and high call variation appear to be key components to female cuckoos pulling off these heists-in-reverse.

Call output of (A) male and (B) female cuckoos during different types weather. Deng et al., 2019.

The data departs from expectations for the other two areas of geography and weather patterns. Overall, there were no significant changes in call output for females when looking at changing latitude. While peak frequency did decrease as latitude increased, maximum frequency, duration, and number of syllables neither significantly increased or decreased with changing latitude. Deng et al. also found a difference from their predictions in that the numbers of syllables and bouts from field recordings and the number of recordings from the online library indicated that both male and female cuckoos have higher calling outputs in the morning, rather than in the afternoon as predicted.

Call output of male and female cuckoos from (A) field recordings and (B) online library recordings, indicating highest call output in the mornings for both male and female cuckoos. Deng et al., 2019.

What are the consequences, then, of the lack of support for Deng et al.’s predictions? Deng et al. surmise that there are purposes to female cuckoos’ calls beyond distracting hosts. Furthermore, it could be that hosts are distracted by female cuckoo’s calls beyond an immediate response. As far as geographic variation, there is the possibility that there is not enough predator variation across the latitudes looked at in this study for there to be much variation in call output. Alternatively, in connection with the idea that there are purposes to female cuckoo’s calls other than distracting hosts, that the calls are not imitations of predators but are distracting to hosts in another manner entirely. Deng et al. mention that most bird species lay egg in the morning, while cuckoos lay egg in the afternoon; exploring the relationship between these egg laying patterns and the pattern found by Deng et al. of female cuckoos’ higher call output in the morning could help us further understand how female cuckoos contribute to the exceptional deception of fooling the rest of the bird world into taking on their offspring as their own.