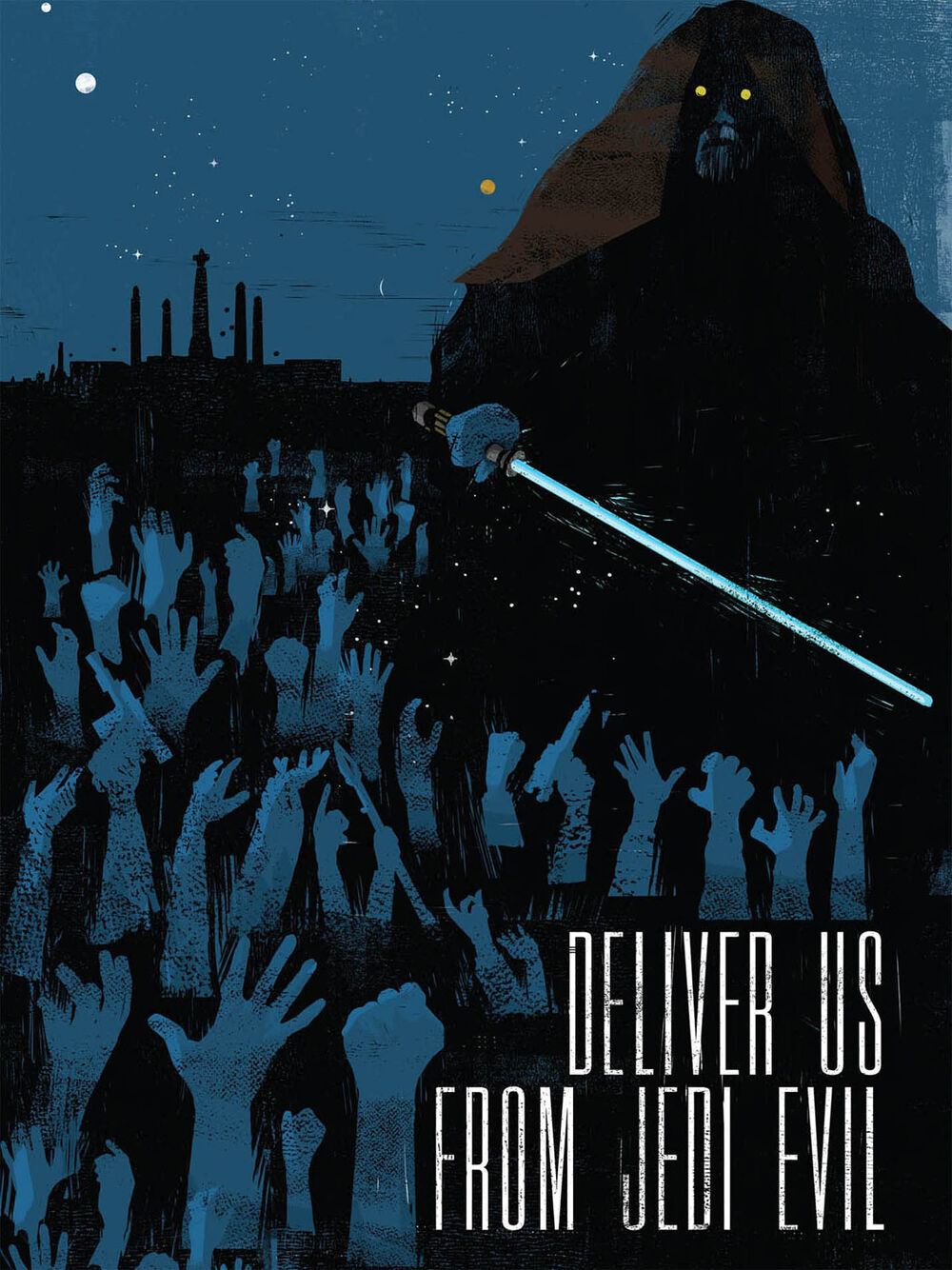

According to Fred Botting, author of Gothic, “Postmodernism, emerging as a global aesthetic style at the end of the 1970s and associated with the wider transformations of modernity, seemed particularly hospitable to the resuscitation of gothic forms and figures.” The theatrical release of Star Wars in 1977 marked one such occasion. The film’s revolutionary blend of science fiction and fantasy is built upon a foundation of gothic tropes and devices from the dysfunctional families and Mephistophelean tempters of the 18th century to the Inquisition prisons and revolutionary anxieties of the 19th century. How might our contemporary understanding of the Star Wars canon develop if we view it through this critical lens that highlights psychological violence, transgression, and excess as a way of unbalancing the hierarchies of good and evil, free will and predestination, tyranny and liberty?

Together we will examine the gothic elements of Star Wars across representational media (including films, storyboards, comics, propaganda posters, short stories, and toys) in order to better understand the ways in which Star Wars engages with the experience of (neo)Imperialism. The Skywalker saga projects a particularly gothic sense of loss and dislocation (of history, culture, identity, and autonomy) by displaying the terrors and traumas of colonization: subjugation, banishment, enforced assimilation, slavery, and genocide. As a paragon of political resistance to the patterns of retributive violence, Star Wars invites us to consider gothic fiction as a crucible for self-knowledge and deliberate action.

You will have an opportunity to focus your interests as you work to compose a multimodal essay of about 10-12 pages (divided into three drafts) that employs film and/or audio clips, hyperlinks, still images, and quoted text to substantiate your argumentative claims. Your essays will then be collected and organized as part of our open access WordPress Anthology. To begin thinking about possible topics for your project, you might consider the following list of gothic tropes and themes:

“Recurrent characters, settings, and props in eighteenth and early nineteenth century Gothic fiction include Faust/Cain/Wandering Jew or Prometheus-like protagonists, Mephistophelean tempters, virtuous heroines, dysfunctional families, gloomy mansions, evil doubles, eerie portraits, wild landscapes, Inquisition prisons, incarcerating monasteries, malevolent monks, rampaging mobs, labyrinthine underground passages, graveyards, corpses, skeletons, crumbling buildings, and crumbling manuscripts (ruins and runes). Recurrent themes and situations include representation of physical and psychological violence, transgression and excess, explicit and implicit sectarianism, revolutionary anxieties, alluring wickedness, dangerous curiosity, threatened damnation, pursuit, persecution, and insanity; in addition to the unbalancing of (contemporaneously accepted) hierarchies of good and evil, free will and predestination, tyranny and liberty, and masculinity and femininity. Recurrent narrative devices include multiple narrators, interrupted—sometimes incomplete—manuscripts or accounts, (wholly or partly encased sub-narratives,) and the alternation of incidents designed to provoke terror with those designed to provoke horror” (From Richard Haslam, “Irish Gothic: A Rhetorical Hermeneutics Approach,” Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 2 (2007): 3-26).

While each of you may explore a topic ranging widely from, say, female subjectivity and the abject to considerations of monstrosity, mourning, and memory, or from scientific medical experimentation and the limits of personhood to the Occult and diabolical uses of magic, the subject of our anthology is the relationship between representation––understood especially in terms of genre and medium––and ‘Otherness’.

Course Texts:

- Star Wars films (on reserve in the Library)

- Star Wars: From a Certain Point of View, various authors

- Roy Thomas and Howard Chaykin, Marvel Comics Star Wars #1–#6

- Imaginary Worlds Podcast Episodes 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, and 56

Recommended Supplementary Materials:

- Gerald Graff and Cathy Berkenstein, They Say, I Say (3rd Edition)

- Grammarly

Habits and Practices of Literary Scholars: Studying representational mass media (print, television, radio, film), reading what others have said about these media in peer-reviewed texts and in new media (podcasts, YouTube videos, Twitter conversations, etc.), and entering into conversation with these texts via our own arguments is the work of professional literary scholars. Once you begin grappling with the ideas of others and responding accordingly, you will have produced literary criticism! Our aim is to hone our ability to do this work well through the deliberate practice of active reading, sound research, cooperative discussion, and recursive writing. Along the way, we will engage writing as a social act that requires feedback at each stage of the process from germination to presentation, and from various readers (including colleagues in class, Writing Center consultants, research librarians, and, of course, me).

You are authors, and you should think of yourselves as such. I will therefore read and respond to your work with the same respect and interest that I give to the authors who submit their writing to the journals I referee. That means, however, that I expect you to learn about and follow the social and cultural conventions of professional academic behavior, which (of course) I will help you learn during the semester as some of these conventions can be a bit mysterious. To be sure, these behaviors aren’t specific to academia––this is just the context in which we will discuss them. This means that you should find the skills you develop and the knowledge that you gain as a result of this course valuable in the increasingly mediated world in which we live. That being said, learning requires a certain amount of experimentation, which can be intimidating and may or may not result in failed attempts. I hope that you do not view these intermittent failures in a negative light as they will surely be of great value to each of you as you work to discover your individual identities as readers, thinkers, writers, and communicators. After all, knowing what doesn’t work is equally as valuable as knowing what does. The end goal of the written components of this course is to deepen your knowledge of how you write and speak––knowledge that will aid you throughout this course, your academic programs, and professional careers. To gain this insight, we will work to develop a strong foundation in the elements of rhetoric that govern all multimodal communication (e.g., audience, purpose, occasion, community, context, and medium).

My hope is that the seminar structure of this course (a joint exploration) will help you feel comfortable experimenting with ideas and strategies that may be new to you, and which may not initially work as intended. I believe that you are capable of excelling in this course, and as such, I have designed both informal and formal writing assignments that include peer and instructor feedback as well as multiple opportunities for revision so that you can achieve the course learning outcomes. You should expect to receive timely and detailed feedback on your in-progress work (you will receive my constructive comments no later than one week after you’ve submitted an assignment). For, just as telling an author that a journal has rejected their work for publication without any explanation as to why does not make that person a better writer in the profession, so too assigning a letter or number grade without an audience-based narrative likely won’t help you improve as a writer. You should expect my comments on your work to reflect the thoughts of a curious yet discerning reader; in return, I’ll expect that you consider incorporating my feedback into subsequent drafts in meaningful––rather than perfunctory––ways.

Learning Outcomes:

- Formulating an Argument: Participate in a scholarly conversation by crafting a paper with a clear, well-organized argument and establishing its relevance to the intended audience.

- Marshalling Evidence: Identify, evaluate, and accurately represent an understanding of primary and secondary source materials (g. summary, paraphrase, quotation) and show the relevance of those materials to their own arguments.

- Writing as Process: Engage various strategies for using writing to analyze and develop their ideas (free-writing, idea-mapping, reverse-outlining, revising, etc.).

- Academic Integrity: Distinguish between plagiarism and the responsible use of sources and cite according to disciplinary conventions.

- Mechanics and Usage: Formulate their ideas in clear and cogent prose while adhering to rules of grammatical correctness.

Successful Participation: You should expect to contribute in an active and generous way to the work of the class as a whole by asking questions, offering interpretations, politely challenging your classmates, graciously accepting challenges in return, and being a productive group member. This means completing the reading and writing assignments prior to each class session and preparing some ideas or questions you’d like to raise with the group. You should expect to invest about 12-15 hours per week reading, writing, attending class meetings, etc. Through discussions, group work, and assignment drafts you should demonstrate that you understand and can apply ideas relating to postcolonial and media theory. This means reasoning logically and creatively to address issues raised by the films, secondary criticism, your peers and me by recognizing the value of different ways of thinking and communicating through a variety of media. In short, teachers, scholars, and students shift between and share all three roles. As such, this course is structured around lectures, discussion, collaboration, workshopping, and reflection.

Participation, Late Assignments, and Attendance: Since participation forms the nucleus of this class, it is imperative that both you and I are prepared to discuss the readings prior to each class session and submit assignments on time. I will lower by one letter grade any late work. Work that is over one week late will not be accepted. Extensions on assignments may be granted, but only on a case-by-case basis. I understand that unexpected emergencies arise, so please budget your time so that you aren’t working on these projects at the last minute in case something does come up. If you run into such a problem that affects your ability to complete a particular assignment on time, I urge you to contact me as soon as possible, and before the assignment is due. Please note, however, that extensions are not automatic upon request.

Diversity: As given in its mission statement, Vassar “strives to pursue diversity, inclusion, and equity as essential components of a rich intellectual and cultural environment in which all members, including those from underrepresented and marginalized groups, are valued and empowered to thrive.” As such, this course will serve students from all backgrounds. The wide array of perspectives that each of us contributes to this class is a resource that will strengthen and enhance our intellectual community. What this means for you, a college student is that you must use this time to prepare to venture forth into a world where diversity and different cultures are the norm.

Academic Integrity and Honesty: You should feel free to study and discuss class concepts with your classmates. Working with a group can be beneficial to your understanding of the course material, and this working style is highly encouraged. However, you should refrain from claiming someone else’s work as your own.

You should read through Going to the Source: A Guide to Academic Integrity and Attribution at Vassar College and bring any questions or concerns you have to class. I am also happy to discuss issues of academic integrity and attribution one-to-one during office hours.

Writing Center: In addition to meeting with me during office hours to discuss coursework and my written comments, I strongly encourage you to visit the Writing Center. Getting feedback benefits writers at all skill levels, and Writing Center consultants can offer a fresh perspective on any writing project, multimedia project, and oral presentation. They offer one-to-one and small group consultations that address everything from brainstorming and developing ideas to crafting strong sentences and effectively using sources. You should feel free to drop in at any point in your writing process––from planning and drafting to revising and editing. To make an appointment visit mywco.com/vassar

Office for Accessibility and Educational Opportunity: Academic accommodations are available for students registered with the Office for Accessibility and Educational Opportunity (AEO). Students in need of disability (ADA/504) accommodations should schedule an appointment early in the semester to discuss any accommodations for this course that have been approved by the Office for Accessibility and Educational Opportunity, as indicated in your AEO accommodation letter.

EOAA and Title IX: Please be aware all Vassar faculty members are “responsible employees,” which means that if you tell me about a situation involving sexual harassment, sexual assault, dating violence, domestic violence, or stalking, I must share that information with the Title IX Coordinator. Although I have to make that notification, you will control how your case will be handled, including whether or not you wish to pursue a formal complaint. Our goal is to make sure you are aware of the range of options available to you and have access to the resources you need. If you wish to speak to someone privately, you can contact a SART (Sexual Assault Response Team) advocate 24/7 by calling the CRC at 845-437-7333.

Grading Criteria for Written Work

A Applies to compositions that are clearly superior in their development and expression of ideas. An “A” paper may not be flawlessly proportioned or totally error-free, but it does all of the following:

- engages the topic thoughtfully and imaginatively; in addition to a detailed understanding of the topic, it has interesting, new or important insights to convey

- develops a thesis or idea using a logical structure; it has sound organization and offers detailed analyses of the evidence cited to support arguments

- uses sentences varied in structure and complexity to achieve a clear and eloquent expression of the ideas it discusses

- makes few or no mechanical mistakes (i.e. spelling, punctuation, grammar, etc.)

B Applies to good, solid and competent compositions. A “B” paper does most of the following well:

- responds intelligently to the topic with a clear thesis that is solid but not striking; ideas do not progress much beyond readings or classroom discussions

- is focused and provides an orderly progression of the argument or ideas, which are reasonable and anchored in examples drawn from readings and classroom discussions

- uses clearly-written sentences, though the style may be slightly awkward at times

- makes some minor mechanical errors, but no major ones

C Applies to satisfactory compositions. A “C” paper usually:

- responds reasonably, if unimaginatively, to the topic; it may have a weak or fuzzy thesis and show some confusion about the topic

- shows some sense of overall structure, but the organization and connection between ideas may not always be clear; it may ramble at times and does not adequately back up points with evidence from readings or class discussions

- uses understandable if not always eloquent sentences; some sentences may not accurately or clearly convey the ideas being presented

- makes many minor mechanical errors and distracting mistakes (words are missing, diction is inconsistent); proofreading is weak

D Applies to less-than-satisfactory compositions. These papers usually lack the coherence and developments of C papers and exhibit significant deficiencies. In addition, a “D” paper often:

- offers a simplistic or inappropriate response to the topic; the thesis is usually missing or may be entirely incorrect (a serious misreading of a text, for instance)

- shows little sense of structure and organization

- makes frequent and serious mechanical errors that impede communication and understanding

F Applies to papers with serious weaknesses in many errors. An “F” paper shows severe difficulties in writing. It:

- offers little substance and may disregard the topic’s demands

- lacks any focus, organization, or development

- misuses words and contains abundant mechanical errors

- is plagiarized in part or as a whole

Adapted from: Harry Edmund Shaw, “Chapter 5,” in Teaching Prose, Ed. Fredric V. Bogel and Katherine K. Gottschalk. New York: W.W. Norton, 1984.

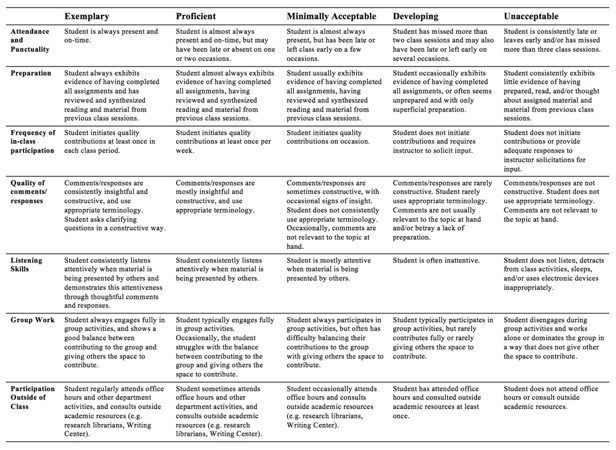

Grading Criteria for Course Participation