The House Wren is a tiny, brown songbird that is commonly found in the backyards of homes across the western hemisphere. Anyone can go out on a still, summer day and notice the tiny bodies of feathers zoom past in the underlying shrubs and tree branches. Once in a while, a child might find a nest in an old shoe box in his garage after his mom nagged at him to do his chores. The beauty of the house wren is exactly this image: its striking simplicity and lack of presence mixed with quite an intriguing set behaviors found only through careful observation.

Songs, Calls, and Development:

House Wrens sing with high intensity in periodic bouts prior to pairing and often did the same later in the breeding cycle to attract more partners. Their song is described as rapid trills of frequency-modulated notes with an average of ten syllables per bout and around four different types of syllables. The largest recorded repertoire of a house wren is 194 songs, although there is likely no sort of ceiling or limit on the size of its repertoire. However, if you only count the songs that are most used by each male, then the effective repertoire of the average male House Wren is about 25 songs (Kaluthota and Rendall, 2013). A close phonetic of the male House Wren is tsi-tsi-tsi-tsi-oodle-oodle-oodle (Bent 1948). Kaluthota and Rendall (2013) also found that only one type of song was shared by all fifteen males, only fourteen songs were shared by more than ten males, and the rest were unique to the individual.

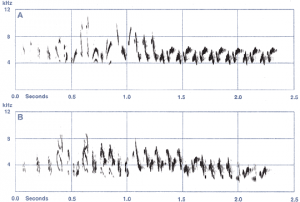

The figure above shows two sonogram examples of male, House Wren songs, both recorded in Ohio.

Johnson, L. 2014. House Wren (Troglodytes aedon), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/380

Interestingly enough, House Wrens are known to practice polygyny, in which a male can have several female partners in a given time period. Cramer (2013) says that her findings showed no correlation between the quality of males and the quality of song, specifically the trills. Older males tended to sing with higher trill consistency, which in turn, attracted more females to its domain, which she also notes is consistent with other studies. This just basically shows that the male House Wrens are much better at finding partners than humans are (at least in comparison to me). All they have to do is trill consistently for a long time and females are more likely tobe attracted. Size and the actual song quality don’t have a significant effect on the rate of finding partners for males.

Song Learning in the House Wren

Tubaro (1990) mentions that because of the presence of dialects, then it is likely that song is learned. Sawhney et al. (2006) mentions that the earliest time for fledglings to start making sounds that resemble some kind of song is around the age of 25 days, and this continues for about another week or two until a clearer song starts to be produced.

In addition, malesand females have their own calls that are commonly known to sound like chatters, churrs or rattles. An unmated male will produce a high-pitched squeak when a female arrives on his territory, and it eventually stops when the female pairs with the male. Both sexes occasionally produce this low “chut” sound at no specific intervals. Both also produce a sort of alarm that warns others of predators in order to tell others to run, distract the predator, and/or protect the nests (Ficken and Popp 1996). In Argentina, two more types of calls by House Wrens were recorded as responses to predators, one being longer and harsher, and the other being shorter and quieter (Fasanella and Fernández, 2009). Overall, there are a wide variety of calls within the House Wrens, and future studies are necessary in order to log and assess the meaning of each one.

Dialects in House Wren song:

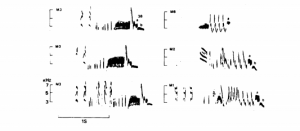

Not much is known about dialects within the House Wren song since very few actual songs are ever shared between a large number of the males. However, despite the enormous repertoire that each male holds, there is very little, noticeable variation between their songs. The repertoire is highly variable among locations and individuals, but there are very distinct characteristics that tie them all together. For example, the sonogram data below shows that there is a repetitive structure to each song as well as a two-part system. The first part tends to include quiet and brief syllables while the second part has more frequent and louder syllables compared to those in the first part (Tubaro, 1990). The diagram below has some sonogram drawings that are also from Tubaro’s study.

Tubaro, P.L. 1990. Song description of the House Wren (Troglodytes aedon) in two populations of eastern Argentina, and some indirect evidences of imitative vocal learning. Hornero 013: 111-116.

Can’t Forget the Kids:

Sawhney et al, (2006) did a study on a population in Colorado on hatchlings and song learning. Hatchlings produce short calls like “peeps” that develop into harsh, broadband bouts of begging after only a week. In 2013, two researchers, Gloag and Kacelnik, found similar patterns in the hatchlings in Argentina. In the Colorado study, the hatchlings would continue this trend for another few weeks with some begging calls mixed in between the time periods of juvenile to adulthood. These calls are very similar to the alarm calls the adults make, which may seem like a problem, but in reality is not since there are slight distinctions that can usually only be noticed after looking at a sonogram. However, the adult wrens seem to pick up on the differences quite well. The hatchlings’ calls are louder and lower in pitch in general, which allows for easier distinction for the adult wrens.

Citations:

1948. Life histories of North American nuthatches, wrens, thrashers and their allies. U.S. Natl. Mus. Bull. 195.

Cramer, E.R.A. Physically Challenging Song Traits, Male Quality, and Reproductive Success in House Wrens. PLoS ONE 8: e59208

2009. Alarm calls of the Southern House Wren Troglodytes musculus: Variation with nesting stage and predator model. Journal of Ornithology 150(4): 853-863.

1996. A comparative analysis of passerine mobbing calls. Auk 113(2):370-380.

Johnson, L. 2014. House Wren (Troglodytes aedon), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online:http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/380

Kaluthota, C.D. and Rendall, D. 2013. Song Organization and Variability in Northern House Wrens (Troglodytes aedon parkmanii) in Western Canada. The Auk 132: 617-628.

2006. Development of vocalisations in nestling and fledgling House Wrens in natural populations. Bioacoustics 15: 271-287.

Tubaro, P.L. 1990. Song description of the House Wren (Troglodytes aedon) in two populations of eastern Argentina, and some indirect evidences of imitative vocal learning. Hornero 013: 111-116.

We have a wren that sings at precisely 7.59 Greenwich mean time every day for 5 minutes and then stops so weirdly that we thought someone had an alarm clock nearby but we live in the countryside with only one close neighbour?

I have a cute house wren that comes every morning. It sits on my string of lights on my back deck and jerks its head while sings loudly. It seems like its trying to tell me something. Does anyine know? 🙂

I was wondering why, when a wren starts chirping the robins start chirping, is it to drown out the wren? It seems like that is what they are doing anyway…

I’m not sure if my little bird that has been staying around my front window of my house since last year is a wren, the picture looks like him/her but the song doesn’t sound the same, my little friend has a very loud Cacacacacaca sound, I can always tell when he/she is near because of that sound he yells out, he especially does it when he’s in my window as to say ‘hey are you in there’ , I put bird boxes out because he sits under the awning over my windows, he has taken interest in them & will visit them daily to check in,on& around them but does not sleep in them. I’ve been dying to find out what type of bird he is.

I’ve befriended a house wren. He eats from my hand. Disappeared for 6 months but is back. Wondering if there is a way to discern his gender? Thought he was a male because he sings all the time but after reading this study, I don’t know.

Thanks!

I have two wrens raising a second clutch of wrens this year. I a 7 whistle song I sing in the yard that is the same every time and I hear a response from one of the wrens every time. She or he flies down to their house and check inside and then fly away. This has been going on since last year and all of this year. They come to our wren house every year. Do the hatchlings come back to our yard or the parent birds? Do you think I could have made a connection with the wrens with my song calling them?

Thank you for your good article. I was wondering why our little wren sang all day long and you answered my questions.