The Chipping Sparrow (Spizella Passerina): Singing Behavior

The Chipping Sparrow, while not flashy or exotic, exhibits complex and unique singing behavior unlike many other bird species. The nuances of this bird’s song are still being analyzed and applied to the scientific world.

Types of Songs and Calls

The calls of the Chipping Sparrow are relatively understudied, but the basics are known. The types of calls include contact calls, used for general communication during various activities such as flight, alarm calls, threat calls, fighting calls, and courtship/copulation calls (Middleton, 1998). Each call has its own distinct sound. For example, the contact call consists of a brief, single tsip and the fighting call is a series of zee-zee-zee notes (Middleton, 1998). Future study might examine possible regional differences among calls, as well as more complex purposes for them in an observational fashion.

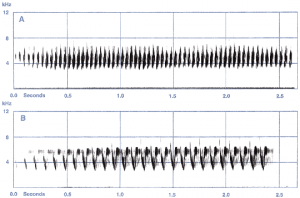

The bulk of research on the Chipping Sparrow has been done on its singing behavior and song types. Only males sing in this species (Liu and Kroodsma, 2007). The bird’s repertoire consists of one song type: this being a single, simple, syllable repeated many times in a trill. While this single song is simple, there are many variations of this song type. Single populations of Chipping Sparrows could contain as many as twenty to thirty different songs, the variation occurring mainly in the repeated syllable (Liu and Kroodsma, 2006).

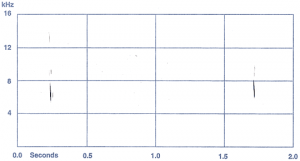

Sample Chipping Sparrow Song:

Initially, it was proposed that the Chipping Sparrow’s simple, repetitive song was used primarily for territory defense, as opposed to complex songs thought to be functional primarily for mate attraction (Albrecht and Oring, 1995). However, a variety of evidence, including that song output diminishes greatly after pairing with a mate, suggested that mate attraction was the primary function of Chipping Sparrow song (Albrecht and Oring, 1995).

There is more to the story, however. More recent research suggests that Chipping Sparrow song may serve two primary functions, each occurring at differing times of day. During dawn, songs are briefer in duration and more rapid in succession than during the daytime (Liu and Kroodsma, 2007). Additionally, singing at dawn occurs primarily on the ground and near territorial boundaries, while singing during daytime occurs primarily at high perches in the middle of territory. Evidence suggests that the Chipping Sparrow sings during the dawn primarily for territory defense, and during the day primarily for mate attraction. Males whose territorial rivals are removed sing less during the dawn, but daytime singing was unaffected (Liu and Kroodsma, 2007). Similarly, daytime singing is reduced after mate pairing while dawn singing is unaffected.

Song structure of the Chipping Sparrow can vary between individuals in a different way than the repeated syllable. The trill rate, how fast the bird can produce the syllables in its trill song, varies between individuals as a result of biological constraints. Individuals who can produce higher performance trills (greater trill rate), are perceived as more threatening to other Chipping Sparrows (Goodwin and Podos, 2014). As a result, Chipping Sparrows work together to repel intruders when this intruder has a higher trill rate than the potential partnering neighbor (Goodwin and Podos, 2014). This suggests that variation in song structure between Chipping Sparrows influences behavior. Further research could investigate how trill rate may influence other behaviors and factors, such as an observational study on trill rate versus territory size or regional differences in trill rate.

Song Dialects

Very little research has been performed on Chipping Sparrows with regard to song dialect. What is known is that 20-30 different songs can be observed within a given population (Liu and Kroodsma, 2006). This suggests that there are no consistently similar songs for specific regions, as they vary so much. However, further research could be done to analyze similarities and differences by region. Particularly, research could consist of observational studies focusing on general trends regarding aspects of the learned syllable and perhaps trill length/inter-song intervals.

Song Learning

Research indicates that song learning occurs during the breeding season following dispersal from the nest (Liu and Kroodsma, 2006). The Chipping Sparrow typically learns during the hatching year, but may also learn in the next spring if it hatches too late in the breeding season. Additionally, the bird will precisely imitate the song of one of its close neighbors, and will not change its song after learning (Liu and Kroodsma, 2006). This phenomenon helps explain the large variety of songs within a single Chipping Sparrow population. Since these birds often move territories between or mid season, they often do not share neighbors with the same song in the next season: this means that there will be a great song variety within a given territory despite birds learning from neighbors (Liu and Kroodsma, 2006).

This song diversity within populations may be an indicator of habitat quality. Study on savannas suggests that invasive plants could affect song diversity. The study compared habitats with native vegetation versus those with the invasive spotted knapweed, which is known to diminish food resources and reproductive success (Ortega et al., 2014). As a result of this invasive species, the prevalence of older birds was lowered. Since Chipping Sparrows typically learn from older neighbors, there was more convergence on song types by juveniles as a result of having fewer adults to choose from. Accordingly, the number of song types was almost twenty percent lower in invaded versus native habitats (Ortega et al., 2014). This data suggests that song variety could indicate habitat quality, as the variety depends partially on the prevalence of older birds.

Conclusion

The Chipping Sparrow’s song, though simple, harbors many complexities and implications, particularly with regard to inter-specific interaction and habitat. Further research could delve deeper into each of these areas, as previously described.

Sources:

Albrecht, D.J. and Oring L.W. 1995. Song in chipping sparrows, Spizella passerina: structure and function. Animal Behavior 50: 1233-1241.

Goodwin, SE and Podos, J. 2014. Team of rivals: alliance formation in territorial songbirds is predicted by vocal signal structure. Biology Letters 10: 20131083.

Liu, W.C. and Kroodsma, D.E. 2007. Dawn and daytime singing behavior of chipping sparrows (Spizella passerina). The Auk 124: 44-52.

Liu, W.C. and Kroodsma, D.E. 2006. Song learning by Chipping Sparrows: When, where, and from whom. The Condor 108: 509-517.

Middleton, Alex L. 1998. Chipping Sparrow (Spizella passerina), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/334

Ortega, Y.K., Benson, A. and Greene, E. 2014. Invasive plant erodes local song diversity in a migratory passerine. Ecology 95: 458-465.

Images (In Order):

Figure 2. Contact Call of the Chipping Sparrow. 1988. Borror Laboratory of Bioacoustics. Web. 5 May 2015 <http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/334/articles/species/334/galleries/figures/figure-2/image_popup_view>.

Figure 3. Variations of the Chipping Sparrow’s Song. 1993. Borror Laboratory of Bioacoustics. Web. 5 May 2015. <http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/334/galleries/figures/figure-3/image_popup_view>.

Karlson, Kevin T. Juvenile Chipping Sparrow. Web. 5 May 2015. <http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/334/galleries/photos/KTK_120202_100078_S/image_popup_view>

Sound:

Terry Davis, XC215873. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/215873.