Throughout history humans have used resources from their environment to aid in their survival and to grow as a species. As humanity has grown, so has the demand of resources. But as time has gone on, our resource use has grown less and less sustainable. According to Smith (2010), Gro Harlem Bruand said, “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Humans used to always respect the environment, and knew to give back to it in order to sustain both themselves and the environment they were a part of. Populations would simply scatter and become nomadic if a city fell apart. But now, such ideas have all but disappeared as humanity is destroying the planet we live on as our demand of resources reaches critical levels.

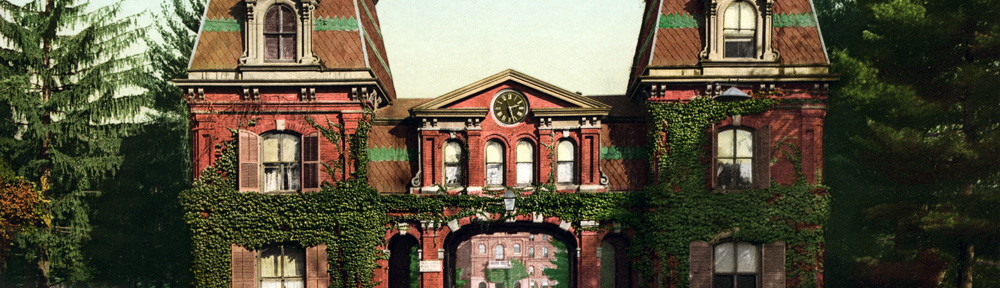

In some ways, ancient civilizations were very similar to our own. They contained societal hierarchies that were similar to our own. They created permanent settlements that grew in number. But ancient civilizations were also very different from modern civilizations. They lacked the technology we posses. Their ideals and religion differed from ours as well. But most importantly, they were moderately sustainable. People back then had to rely on their environment a lot more than we do today. They relied on their environment to give them what they needed to survive. If their was a bad drought and the crops died, then there was no food for the city. Nowadays, farmers can simply pump water up from the ground to irrigate their crops, or get the water delivered to them from somewhere else. They also spray pesticides and chemicals to improve the crop yield. They contaminate their environment to survive. Ancient civilizations used the materials around them to build their homes and produce goods. Modern civilizations burrow into the ground and send and receive goods from around the world.

Modern society gains many of its resources through mining and related activities. This can destroy and destabilize the land around it as well as contaminate nearby water tables.

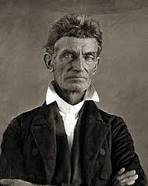

We overproduce goods to gain a higher profit while not realizing that in doing so we are overusing our resources to the breaking point. Some groups like the Native Americans valued the land and thought it belonged to no one. Now we have become obsessed with gaining land and resources to use for ourselves rather than the entire group. According to Smith (2010) “Private property laws ensure the continuing organization of space, even after physical destruction”. But ancient civilizations were not perfect. Eventually they too overused their resources and eventually collapsed. However, our civilization has reached that phase faster than most others before us. we have managed to reach the phase that took the Maya more than 500 years to reach in less than half the time. If we want our civilization to continue, we must eventually learn to be just as sustainable as those ancient civilizations were.

Sources:

http://wideurbanworld.blogspot.com/2011/02/were-ancient-cities-sustainable.html

Additional Resources:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3327537/

http://uvamagazine.org/articles/the_trouble_with_civilization