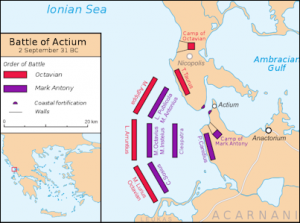

The Western world considered Egypt to be one of the greatest civilization in history. Most of its fame arose from the sense of wonderment surrounding its massive pyramids, and from its legendary people and histories. Cleopatra was a main figure that American children learn about when they first begin to discuss Egypt. The fall of her empire was often attributed to the Roman victory over Egypt in the Battle of Actium in 30 B.C.. Whereas this loss was previously comprehended by conditioned notions of Egyptian weakness through infighting, decadence, and incest, recent archaeological findings hinted that the environment and climate may have had a larger impact on the outcome of the battle. Evidence from ice core data, Islamic records of the water levels in the Nile River, and “ancient Egyptian histories” written on papyrus suggested that a volcanic eruption in 44 B.C. had a massive impact on the stability of Egypt under Cleopatra’s reign.

The result of the eruption was widespread vulnerability. The intrusive eruption disrupted the flooding of the Nile River, thus impacting agriculture, trade, and social organization. Famine ensued due to lack of fertility in local soils to produce essential crops and sustenance for consumption and trading. Additionally, immune systems severely declined with the lack of proper nutrition or energy, which contributed to the widespread disease and famine which swept the nation. Lastly, social unrest surrounding the irregular patterns of the river caused strained trade and social relations between groups of people and caused either conflict or the need for migration. All of these consequences of the volcanic eruption in 44 B.C. contributed to the immense vulnerability of Egypt at the time, making Cleopatra’s reign less authoritative, and making it easier for the Roman empire to claim victory over Egypt in the Battle of Actium in 30 B.C..

I found this finding interesting because it proved the necessity of critical thinking and revisitation of academia’s previously conceived notions and ideas surrounding political and social phenomena. While infighting, decadence, and incest may have contributed to the instability that Egypt felt at the time, it was important to search for more context in order to reveal clues about the rise and fall of “past” civilizations and empires. Looking at history with such a critical lens could elucidate perceptions of the future cycle of empires in the world and help to understand the meanings behind and implications of international interactions today.

Sources and Additional Readings:

https://www.archaeology.org/news/6027-171017-egypt-volcano-nile

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/oct/17/asp-or-ash-climate-historians-link-cleopatra-demise-volcanic-eruption-nile

http://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-00957-y

http://factsanddetails.com/world/cat56/sub366/item2032.html

https://thisblogisratedpgforpropheticguidance.wordpress.com/tag/battle-of-actium/