One of the most interesting aspects of sensory and evolutionary ecology is the concept of mimicry between or within species. Mimicry is when a species has evolved a trait that allows it to imitate the appearance, behavior, scent, or sound of another species for the purpose of survival or reproduction. A great example of mimicry is Viceroy butterflies mimicking the color patterns of Monarch butterflies. Due to their consumption of milkweed, Monarch butterflies have a foul taste and their colors are avoided by predators, thus by mimicking their appearance Viceroy butterflies have gained an evolutionary benefit.

Mimicry can also occur within a single species between organisms of the opposite sex, and this mimicry is almost always used for reproductive benefits. Scientists recently performed a study focusing on the potential mimicry that exists within a Chinese cicada species, Subpsaltria yangi. Previous research on these cicadas revealed that this species possesses an unusual system for creating communication signals.

What was their hypothesis?

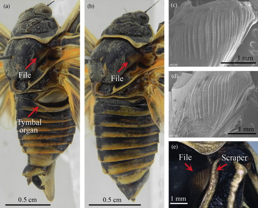

In almost all cicada species, males produce mating calls by using a tymbal organ system, which is a membrane used to resonate sound produced from muscles in their abdomen. In most species the females have no physical capability to respond to these calls. However for Subpsaltria yangi, in addition to the male’s tymbal calling system, both males and females possess a stridulatory system that is very common in many insects like crickets, but not in cicadas. The stridulatory system relies on generating friction calls from rubbing their forewings against their file-like ridged abdomen.

Because this species was thought to be extinct for over thirty years until their rediscovery in 2011, no work had been done analyzing the calling behavior of these cicadas in terms of the two structures. Therefore, the researchers in this study were interested in determining the physiology and function of this surprising dual calling adaptation. They hypothesized that the similarity in structure between the male and female stridulatory systems could be due to the evolution of mimicry within the species for a reproductive benefit.

What did they learn?

During this study, the researchers observed the natural behavior of the male and female cicadas and recorded their calls. Analysis of the behavior and calls proved that males quickly alternate between their tymbal and stridulatory systems when producing mating calls. The researchers also found that between males and females, their stridulatory organs are very similar in terms of their structure and sound production abilities.

In the second portion of the experiment, the researchers caged female subjects and observed their behavior while playing different prerecorded male calls. These playback calls included tymbal sounds alone, stridulatory sounds alone, and a natural recording of a mix of both call types. The researchers found that females exhibited calling responses when listening to both the tymbal calls and the natural mixed calls, but that the responses were much higher in the mixed call trials. They believe that since females didn’t respond to male stridulatory calls alone, they must treat these calls the same as ones coming from other females. These results show that males alternating between tymbal and stridulatory calls effectively imitate a mating call/response between a male and a real female, confirming the researchers’ hypothesis of sexual mimicry. When a female listens to a call and response interaction between a male-female pair, she becomes competitive and begins calling in order to attract the male for herself. By instigating competition between a real female and an imitation female, males can find females faster and thus have better success with reproduction when the real female falls for the auditory trick. This mimicry call still poses a risk of attracting the competition of other males, but it is likely that the males of this species have evolved their hearing in order to ignore acoustic signals consisting of alternating patterns.

This is a truly fascinating case of sexual mimicry within a species and the discovery of a species of cicada that utilizes both tymbal and stridulatory structures for calling changes preconceptions on the limitations of insect auditory communication. To learn more about this study, you can take a look at the following article:

References:

Lou, C., Wei, C. (2015). Intraspecific sexual mimicry for finding femakes in cicada: males pricde’female sounds’ to gain reproductice benefit. Animal Behavior 102, 69-76.

Rogers, K. (2011). Mutual Mimicry: Viceroy and Monarch. Encyclopedia Britannica Blog. Retrieved from http://blogs.britannica.com/2011/05/mutual-mimicry-viceroy-monarch/