We all know that humans are the most intellectual species in the world, but have you ever wondered how smart other animals are? Many people with pets are familiar with the concept of positive reinforcement and rewarding their best furry friends for a certain action or behaviour. An easy everyday example would be giving your dog a treat for playing dead or trotting over to you when you call its name. Therefore it is evident that animals can extract causal knowledge from the environment and predict future events, such as being given a reward, and use those predictions to decide what to do next (Sloman 2009).

On top of this, humans also have the cognitive capacity to use counterfactual thinking which is essentially the ability to understand that certain actions do not produce certain consequences or rewards and use these absent events in future decision-making. For example, have you ever just walked by a beautiful woman or a sexy man in the mall and moments later, wondered “Dang, I wish I had asked for her number! She could have said yes!” or “I should have asked him for coffee. He probably had time!”? By thinking of alternative decisions to past events, you are thinking counterfactually! Before, it has been thought that only humans possess the intellectual capacity to extract information from this process of reasoning. In Wikipedia and many other sites, the concept is linked as being a “human tendency” (wikipedia.org). However, table-turning evidence from Sydney, Australia make sensory ecologists believe that we may have underestimated these creatures.

In the past, the causal thought process of linking an action with a reward (i.e. positive reinforcement) has been seen in many animals such as monkeys, dogs, birds, and rats. However, Laurent & Balleine at the University of Sydney just recently published convincing evidence that rats possibly possess the ability to think counterfactually and are not as simplistic as we imagined.

So how smart are these animals? In the study, the rats were first taught to make positive predictions where they associated a certain lever with a reward and another lever with just regular pellets. Afterwards, they were conditioned to establish negative predictions (i.e. no reward) for pressing a certain lever. The key here was that if they could used the information of a negative stimulus (one lever) and direct their decision-making towards choosing the other lever, then it is most likely that the rat is thinking “Well I chose this lever last time and I didn’t get my sugar. Because that lever didn’t work, I will choose the other lever.”. Being able to extract information from non-successful predictions is strong evidence of counterfactual reasoning! In fact, rather than shying away from the negative lever, rats were able to flexibly and actively use the information from counterfactual relationships in altering their decision-making in trials in finding the reward.

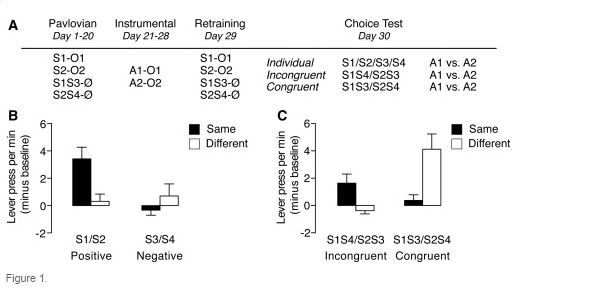

In the first 20 days, mice were conditioned with the following: S1-O1= Stimuli associated with negative outcome (pellets), S2-O2= Stimuli associated with positive outcome (sugar). S1S3-Ø= Conditioning S3 to be a negative stimulus to no outcome, S2S4-Ø= Conditioning S4 to be a negative stimulus to no outcome.

Afterwards for 9 days, they learned to associate a left/right lever (A1/A2) with pellets/sugar (O1/O2). Lastly they had a day of retraining. Results show that (in B) positive and negative stimuli affected the decision-making in the rat (positive stimuli directed choice towards the action (i.e. same) which led to a common outcome as before). However, negative stimuli failed to establish any significant difference between the two lever decisions.

In C, incongruent stimuli lead to an increase in responding on the same action indicating the positive stimuli guided the rat to take the same action. On the other hand, congruent stimuli led to the different action (choosing the other lever) indicating an association between the compound stimuli and the absence of a wanted outcome (sugar).

Overall, being able to reflect on both the consequences of their actions as well as (most importantly) consequences that their actions do not cause possesses strong evidence that rats (or animals) possess the ability to make decisions based on counterfactual reasoning which was once believed to be only associated with humans. In addition, rather than avoiding decisions altogether and actively selecting the lever proves that they can actively engage and manipulate counterfactual information provided to them.

So how smart are animals really? Are we the only ones that can reason or think a certain way? With this study proving that they have potentially higher cognitive abilities than we anticipated, are we really different from them as we imagined? So next time you train your dog or mouse, just take a moment to wonder about what may be going in their furry heads and what information they are obtaining through other means outside your training.

References

Laurent V., Balleine B.W. (2015). Factual and Counterfactual Action-Outcome Mappings Control Choice between Goal-Directed Actions in Rats. Current Biology (25), 1-6..

Counterfactual Thinking. Wikipedia.org. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Counterfactual_thinking. Accessed April 15 2015.