Nobody likes to be eavesdropped on. It’s an invasion of privacy, someone listening to words not meant for their ears. But if you think that is uncomfortable, imagine if instead of another person eavesdropping, it was a parasitic midge using your conversation to find its next meal—your blood!

Many animals have to worry about eavesdropping in a much more serious way than we humans do, as predators and parasites often use the communication signals of their prey or hosts to locate their dinner. We can think of hawks zoning in on squirrel sounds, cats listening in on the squeaking of mice, or wolves tracking an elk through the forest using its calls. It is easy to imagine birds and mammals picking up on the sensory signals of other animals, but amazingly enough, ostensibly simpler animals like flies can use the exact same technique! One particular study published recently in Ethology looked at this phenomenon in frog-biting midges, which use frog calls to find their hosts with amazing sophistication and complexity.

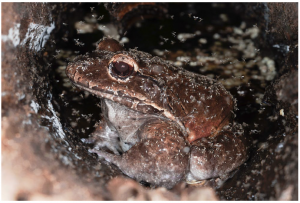

Frog-biting midge bugguide.net

Beyond simply listening to the frogs’ calls, these frog-biting midges make choices about which hosts to target based upon their calls! Here is where this study’s focus lay—in exploring what possible preferences the midges have for different calls, and what about these various calls might attract them. Any preferences the midges have for different calls could enlighten us on how the frogs’ calls may have evolved to escape the preference of a detrimental parasite such as the midge.

The primary traits of the frogs’ calls that the scientists behind this paper were interested in were frequency and duration—two core tenets to sound modulation. The researchers performed their experiments in the pacific lowlands of Costa Rica, using synthetic calls varying in frequency and duration as well as natural advertisement calls to set up traps for the midges. This trap information was then used to determine which calls the midges were most attracted to. The researchers hypothesized that the midges would be most attracted to synthetic calls that were similar to the natural calls of their hosts.

Bullfrog covered in midges Ethology Virgo et al. paper

The results of the study showed that the midges were attracted to a wide variability of both synthetic and natural calls! The synthetic calls that trapped the most midges had a relatively lower frequency and a longer duration. When it came to natural calls, the midges displayed clear preferences for the calls of specific species of frogs. The call of the giant bullfrog attracted by far the most amount of midges—up to 14 times as many as other frog species’ calls! The natural calls that were the most effective at attracting midges matched the criteria of the artificial calls for attraction efficiency—namely, the variables of frequency and pulse duration. This matches up with the prediction made by the researchers before completing the study.

Significant variation in the species of midges caught in the traps was also found. This suggests that there is little to no host-parasite specificity—instead it appears that the midges are generalized in their locating of hosts through call listening. This finding only refers to host specificity based on auditory cues—there may be other types of host-recognition based upon other sensory information, such as chemical cues.

So why do the midges have these complex discriminatory abilities around frog calls? One answer could be that certain call traits give clues about other favorable host traits. The midges appear to prefer low frequencies of calls—and low frequencies often correlate with larger body size. Bigger frogs have less defensive systems against midges, which is why they may be preferable hosts. The bullfrog supports this hypothesis, as a very large frog with very low defensive strategies against midges, and the call that the midges most preferred.

Bullfrog Wiki Commons

All of these results tell us that midges have complex acoustic cues that they are using to detect and locate frog calls—far more complex than we might imagine a parasitic fly to be capable of!

Of course one important caveat here is that call listening is probably only one method that the frog-biting midges use to find their hosts—there is still a whole suite of other sensory systems yet to be explored. Regardless, it is pretty amazing (and pretty creepy) that these midges are out there lurking quietly, frogs calling all around them, listening carefully to decide where their next host may be.

For more information, check out the paper that was the subject of this blog post:

Virgo, J., Ruppert, A., Lampert, K., Grafe, T., Etlz, T. May 2019. The sound of a blood meal: Acoustic ecology of frog‐biting midges (Corethrella) in lowland Pacific Costa Rica. Ethology vol. 127:7. pp 465-475.