Host species’ (species that host parasites) main defensive strategy against brood parasitism is the hosts’ ability to recognize and reject parasitic offspring (i.e. pushing the parasitic egg out of the nest). Brood parasitism is when one organism (brood parasite) tries to trick another organism (the host organism) to raise the young of the brood parasites. Birds have exquisite visual discrimination ability. To prevent their eggs from being tossed from the nest, brood parasites mimic the visual appearance of the egg of the host species. Birds also have an exquisite sense of smell. It is predicted that odors might play a role in rejection of brood parasitic eggs. If this prediction is true than some level of odor mimicry (mimicking an odor) might be used by brood parasites to trick the host. It is possible that hosts refined their sense of smell discrimination to discern between and mimic and the real host eggs. Because of this refinement, brood parasites will try to make their eggs smell more like host eggs. This back and forth refinement is an example of antagonistic evolution. This study tested the effect of foreign scents on the probability of recognition and ejection of experimental parasitic eggs (great spotted cuckoo eggs) in magpie nests.

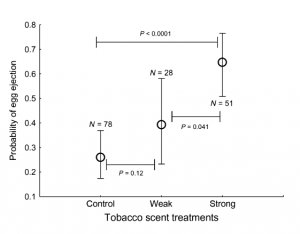

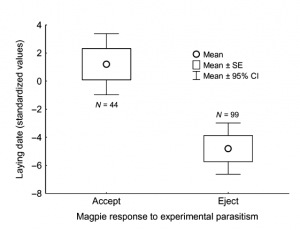

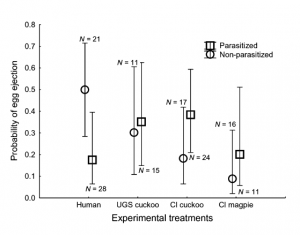

Model eggs (fake cuckoo eggs) with the strongest tobacco scent experienced the highest rate of rejection (egg was pushed out of the nest) from the magpie nest, as seen in figure 1. Figure 2 shows how magpies that bred later in the breeding season accepted the model eggs more often than those who bred early in the breeding season. The effect of experimental treatments (the addition of human scent, uropygial gland secretion of the great spotted cuckoo, or cloacal samples, where the egg exits the bird and also the source of waste material, from cuckoos and magpies) on rejection rate in unparasitized magpie nests (nests without model cuckoo eggs) was significant (fig. 3). In unparasitized nests, experimental treatments with human scent and treatments with cuckoo uropygial gland secretion (oils used in birds to preen feathers) experienced the highest ejection rate (fig. 3).

Figure 3: Probability of egg ejection under four different experimental treats for non-parasitized and parasitized magpie nests.

These results show that magpies were able to use their sense of smell from tobacco smoke to identify and eject model cuckoo eggs. Magpie eggs treated with cloaca of magpies received and lower rejection rate. Magpie eggs treated with human scent and urogypial secretion and cloaca scents from cuckoos received an intermediate amount of rejection. This proves that magpies use their sense of smell along with visual cues to eject foreign eggs from their nest. The possibility that other birds do the same is very likely. It is also possible that odors of hosts and brood parasites coevolved. This research suggests that the short time used by parasitic cuckoos to lay their eggs may be to reduce odor deposition on the egg as well as to avoid detection. The authors hope that this research will lead to further research on the role of the sense of smell in other brood parasites and hosts, in egg ejection and even nestling ejection. Future studies in this field may allow for a more complete picture of coevolution in the context of brood parasites.

Sources:

Shpirer Y. “Eggs in the nest (4 Hooded Crow eggs 2 Cuckoo eggs).” Photo.net. NameMedia, Inc. N.p., Web. 12 May. 2014.

Soler J.J. et al. 2014. “Recognizing odd smells and ejection of brood parasitic eggs. An experimental test in magpies of a novel defensive trait against brood parasitism.” J . Evol. Biol. 27:1-6.

Wilkes M. “Magpies in a nest.” Naturepl.com. Wildscreen. N.p., Web. 12 May. 2014.