Mimicry in the animal kingdom includes behaviors or features of one group (species or sex within a species) that imitates another group in order to gain some kind of advantage, whether that be protection, sexual attraction, or some other benefit. Intraspecific sexual mimicry is a behavior where individuals of one sex within a species take on the appearance of the opposite sex in order to attract mates. This is common in many species of birds, reptiles, amphibians, cephalopods, mammals, and insects. The most studied form of this mimicry is visual imitation. The paper by Luo and Wei (Intraspecific sexual mimicry for finding females in a cicada: males produce ‘female sounds’ to gain reproductive benefit) is the first to describe acoustic behavior as intraspecific sexual mimicry.

A type of mimicry (Batesian) where a harmless species

A type of mimicry (Batesian) where a harmless species

resembles a toxic species for its own protection

Source: Conant, R. 1958. A Field Guide to Reptiles and

Amphibians of the United States and Canada East of the

100th Meridian. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, MA.

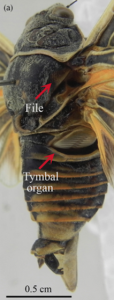

Many insects, including cicadas, use sound communication for mating purposes. It usually includes acoustic advertisement by the males, and a response by the females to indicate availability. It was previously known that male cicadas produce sounds with their tymbal organs, located on their abdomen, and females respond with sounds produced by a stridulatory mechanism composed of a scraper and file. Changqing Luo and Cong Wei, researchers in China, recently found that in a species of cicada found in China, males also produce sounds via the stridulatory mechanism. Because of this observation, they wanted to determine the exact mechanism of the stridulation and the function of the sound that is produced for both sexes.

Male cicada sound Female cicada stridulatory

production structure sound production structure

Source: paper Source: paper

Subsaltria yangi was previously thought to be extinct, as it had not been seen since 1989. However, researchers located a population in 2011, found in the Chunshugou Valley of the Helanshan National Nature Reserve in China. Observations and experiments were conducted over the course of three years (2011-2013) during the cicadas’ summer emergence. They were observed in both natural conditions and in cages after capture. Their behaviors and sound productions were recorded and analyzed, as well as the morphology of the components involved in stridulation. The stridulation mechanism was compared between males and females to see if there was a difference. Scraper ablation (removal) experiments were performed on males to see the differences in sound produced. Researchers also performed playback experiments with both males and females to determine how they responded to the different acoustic signals, looking at natural male sounds (tymbal organs and stridulatory methods), male tymbal organ only, male stridulation only, or female stridulation.

Subsaltria yangi was previously thought to be extinct, as it had not been seen since 1989. However, researchers located a population in 2011, found in the Chunshugou Valley of the Helanshan National Nature Reserve in China. Observations and experiments were conducted over the course of three years (2011-2013) during the cicadas’ summer emergence. They were observed in both natural conditions and in cages after capture. Their behaviors and sound productions were recorded and analyzed, as well as the morphology of the components involved in stridulation. The stridulation mechanism was compared between males and females to see if there was a difference. Scraper ablation (removal) experiments were performed on males to see the differences in sound produced. Researchers also performed playback experiments with both males and females to determine how they responded to the different acoustic signals, looking at natural male sounds (tymbal organs and stridulatory methods), male tymbal organ only, male stridulation only, or female stridulation.

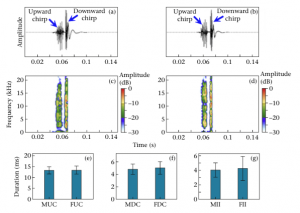

While both males and females had a very similar file and scraper that made up the stridulatory mechanism, only males had a tymbal organ (pictured above). The presence of the stridulation mechanism in the male is a new find, but it was previously known that females do not contain a tymbal organ. The male mating call included both techniques produced alternately. The ablation experiment where the researchers removed the scraper on the males resulted in only the acoustic signal from the tymbal organ being produced, as expected. This shows that the scraper was essential to the stridulatory signal, just like it is in females. When comparing the stridulatory sound produced by males and females, the researchers found that the sounds were almost identical; both had broad spectrum frequencies with the same duration during each part of the sound (pictured below).

Comparison of male (B, D) and female (A, C) cicadas

stridulatory sound produced by file and scraper.

Duration of various aspects of the calls were also compared

(M – male; F – female; UC – upward chirp;

DC – downward chirp; II – interchirp interval)

Source: paper

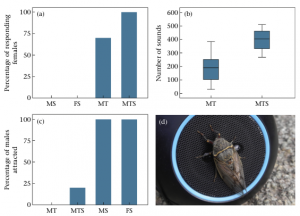

During the playback experiment researchers found that neither the male nor the female stridulatory sounds could elicit a response from the female cicadas when they were played alone. When coupled with the tymbal organ songs, all the females responded. A lower amount of females responded when only presented with the tymbal organ, and they produced a smaller amount of sounds in response when compared to the natural male signal. Also, concurrent with the results of similarity between male and female stridulatory sounds, the male stridulation was able to produce phonotactic responses from males, as well as the female stridulatory sounds.

Playback experiment results (M – male; F – female; S – stridulation; T – tymbal sounds)

Source: paper

Based on their results, researcher believe that the male’s stridulation sound is a mimic of the females in an effort to simulate competition of other females so that the real females respond faster. This is an enticing explanation since the signal does not contain any information by itself and is identical to the female calls. More females responded when both the tymbal sounds (which contains information about mating availability) and the stridulatory sounds were present than just the tymbal sounds, which suggests that the stridulatory sound increases the female response. They propose that this is another example of intraspecific sexual mimicry, and the first described that includes an acoustic signal. One cost of this system that researchers indicate is the potential for males to hear another male’s stridulation call and confuse it with the female call, thereby wasting energy in its effort to mate. However, since the mimicry does exist, the tradeoff that is present must not limit fitness by a noticeable amount, otherwise it would be selected against. The researchers also propose that the males may have evolved to ignore the stridulatory calls when combined with the sounds of the tymbal organ. Either explanation would make the cost of the mimic minimal. Overall, this study presents one of the first looks at acoustic intraspecific sexual mimicry, and more examples need to be studied to understand the benefits and costs of this form of sexual selection.

Video 1. Male cicada mating call

Source: Cicada sound from James Taylor, YouTube.

Video 2. Female cicada stridulatory response

Source: S1 Video from Luo C, Wei C (2015). “Stridulatory Sound-Production and Its

Function in Females of the Cicada Subpsaltria yangi”. PLOS ONE.

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0118667.

It is an interesting introduction of intraspecific sexual mimicry about acoustic behavior. But there is a fact that needs to be clarified. In most cicada species, only males can produce sounds using their timbal organs, while females can not produce any sound–they are mute. In periodical cicadas, when males calling, females flick their wings to respond, but not producing stridulation. However, in the cicada Subsaltria yangi, females can produce stridulation, which is unusual in cicadas. Males in most cicada species can only produce timbal sounds, while males of S. yangi can produce stridulation which is very similar with females’. So the authors proposed that males mimic female sound. I think it is credible.