We hate ticks in the summer. Those greedy eight-legged bloodsuckers bury their heads into our skin and get all the free food they want. They are also dangerous transmitters of diseases and can possibly leave you ill for a long time. Well, for the same reasons, fishes hate parasites too. Larger fishes can suffer from ectoparasites, who anchor themselves on the fish’s skin and suck the living juice out of the poor host. But fishes do not have hospital emergency rooms, where we can go to have the ticks removed by a doctor… Or do they?

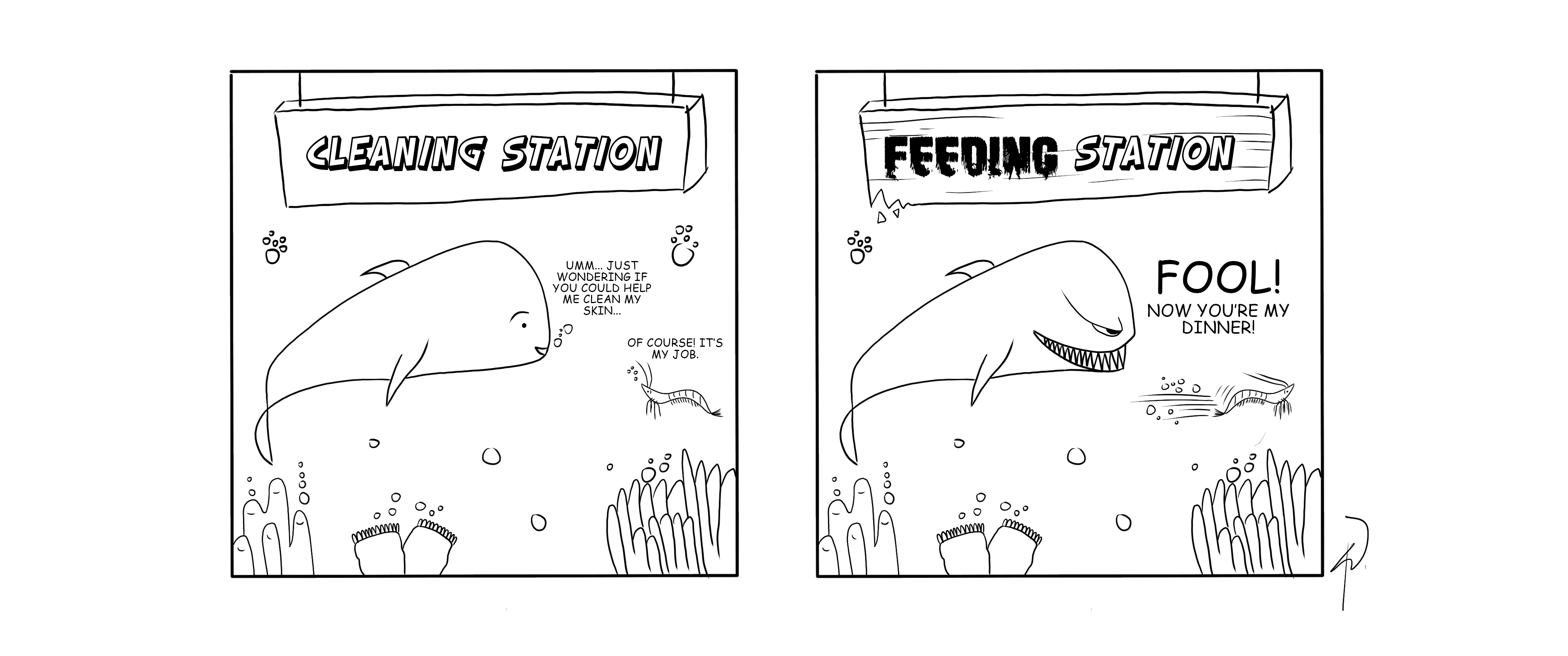

On the coral reefs of many oceans are “cleaning stations” maintained by voluntary “cleaners”. These small fishes or crustaceans form a fascinating mutualism with their clients here. Client fishes sick with parasites congregate at these stations and make poses to show that they are ready for cleaning. The cleaners then come over and eat the ectoparasites or dead tissue off their clients. It is a win-win situation – cleaners get their food, and clients get their health back. But every coin has a flip side, and this harmonious, lovely scene can go really wrong. Some of the clients normally predate on their cleaners, and it does not take much effort to turn the cleaning station into a feeding station. (Well, nature is not always a fairy tale.)

Surprisingly, cleaning mutualism does not die out because of these cheating behaviors, and scientists are wondering why. A group of researchers lead by Eleanor Caves in North Carolina investigated into how behavioral changes in the cleaners help them reduce predation risk from their clients. There are two possible ways: (a) cleaners can choose not to clean predator clients, and (b) cleaners can signal to advertise their cleaning services so that clients do not confuse them as food. The team deployed GoPros at two ocean cleaning stations to observe the interactions between cleaner shrimps and their clients.

It turned out that predatory clients were indeed less likely to get cleaned. Among clients who made the ready-for-cleaning pose, only a quarter of predatory clients were cleaned, compared to almost half in the non-predatory clients. Furthermore, when interacting with predatory fishes, cleaner shrimps often performed a leg-rocking dance.

How can the shrimps tell if a client is a predatory or a non-predatory one? Are these leg-rocking dances directed specifically at predatory clients? After analysis, Caves and colleagues found that when clients are larger in size, cleaner shrimps are more likely to rock their legs before approaching. But these shrimps are known for their poor vision, and they must have a simpler way to tell whether a client is dangerous or not than assessing them in detail. Thus, the researchers presented fake clients (assorted shapes on an iPad) to cleaner shrimps in an aquarium, and found that the shrimps do more leg-rocking when the screen shows black shapes or decreases in brightness.

The aforementioned two possible explanations now have supporting evidence. Cleaner shrimps clean non-predatory clients more often, possibly to avoid predation risk. The leg-rocking dance may act as a signal specifically for predatory clients, and the shrimps may be able to distinguish client type by reductions of light. Though the team did not find a strong connection between client size and client type, it is possible that the bigger a client is, the more light it blocks, and the cleaner shrimp can thus judge its own safety.

These findings shed new light on a problem that has been puzzling scientists – how does cleaning mutualism persist? The cleaners face constant risk during their work because their clients can be dangerous to them, while the clients themselves do not have to worry about such things. This unequal risk might be mitigated by the cleaners adjusting their behaviors based on client type, so that the relationship is not ruined. There are also two other cleaner species in the same area who share similar behaviors, and this research suggests convergent behavioral evolution. But for now, let us just get amazed by the beauty of nature – no permanent friends or enemies, it is all about killing or getting killed 🙂

Reference: Caves, E. M., Chen, C., & Johnsen, S. (2019). The cleaner shrimp Lysmata amboinensis adjusts its behaviour towards predatory versus non-predatory clients. Biology Letters, 15(9), 20190534. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2019.0534