Northern Mockingbird: Mimus Polyglottos

Northern Mockingbirds are not typical songbirds, as half of their repertoire is comprised of songs that are mimetic, meaning they are songs learned from other species, rather than just learned from adults of their species (Gammon and Lyon, 2017).

Song and Calls

Mimetic song is often used more in the breeding season, however mockingbirds will learn new sounds throughout their whole life. Because Northern Mockingbirds are mimics, their song has similarity to locally produced sounds from a model, however, their song can also consist of non-mimetic vocalizations and other mockingbird song types (Gammon and Lyon, 2017). There are three types of unlearned song that mockingbirds will sing and these are called loud hews, soft hews and chat calls (Zollinger, Riede and Suthers, 2008).

Their song varies, because it is composed of long vocal sequences, containing many repeated sounds from their repertoire, often referred to as song types (Gammon and Lyon, 2017). In fact, mockingbirds can have anywhere from 45-203 song types, and their song will consist of different bouts, each repeated many times and then followed by a different song. Researchers look at mockingbird song with several components in mind: versatility, bout length, and recurrence interval. However, researchers have not looked into repertoire size in relation to region. About 35%-63% of song is recurring from year to year, so the repertoire increases with age (Derrickson and Breitwisch, 2011).

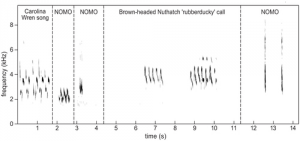

Figure 1 shows a spectrogram of a phrase of a northern mockingbird song, distinguishing between the mockingbird’s mimetic song and other species’ song. Mockingbirds include large silences between repeated song types, enabling us to listen to the different components of their complex song, before moving onto the next song type (Gammon and Lyon, 2017). Mimetic song covers much higher frequencies, which is believed to better attract females during breeding season (Gammon and Lyon, 2017). These occur in alarm and non-alarm contexts (Gammon, 2014). Most singing occurs in the morning, but nocturnal singing also happens when there is bright light of a full moon, or artificial light. They start singing around a half hour to an hour before sunrise.

Figure 1: The Carolina Wren song and Brown-headed Nuthatch ‘rubberducky’ call are examples of songs mimicked by the mockingbird. Each vertical dotted line accounts for the separation of song types, so in this example, there are five song types represented.

(Gammon and Lyon, 2007)

Mimicry in Mockingbirds

As mimics, Mockingbirds replicate other sounds including other species’ songs or calls, vocalizations of other non-bird species, mechanical sounds and other mockingbirds’ songs. They are open-ended learners, meaning they learn song throughout life, and the majority of song is not innate. Also, due to being mostly sedentary birds, it is believed most song is learned from local species and neighboring birds (Derrickson and Breitwisch, 2011).

The frequency of mockingbird mimicry is highest in the late spring prior to breeding and lower in the non-breeding season (Gammon, 2014). Mockingbirds utilize the syrinx to make complex sounds and expand their repertoire, somewhat like using two voices because the syrinx is capable of self-harmonizing (Zollinger, Riede and Suthers, 2008).

Dialects and the Environment

Dialects are not studied, and it is unclear if dialects are present in Northern mockingbird song. It is unlikely there are extreme dialects because their song repertoire is so vast, and because they are such sedentary birds. It has been studied how these birds react with their environment, including the fact that they have different songs for when they are in flight versus not in flight. Also, some trees are favored by males, and will be passed onto other members of the generation or future generations. They also will sing while putting their nests together, but otherwise will not sing from their nests (Derrickson and Breitwisch, 2011).

Looking Ahead

In one study, it was shown that males with more testosterone sing more, which allows them to find a mate more easily, which suggests that increased testosterone levels can be the cause of increased use of mimicry in mockingbird song (Gammon, 2014). Sometimes, mockingbirds have trouble directly mimicking sounds that are physiologically hard to understand and produce. This leads to the idea that sound production mechanisms help mockingbirds choose their models (Gammon, 2013). This is one pathway that can be opened up to learn more about mockingbird song. Do mockingbirds choose models that are similar to their sound, or do they choose models that are more unique and different than their sound? A study can be created in which we experiment using a mockingbird in the lab and play a series of different models with varying levels of acoustic similarity.

Mockingbirds are said to be open-ended learners, however, it is not clear when their exact learning times are, and if their repertoires shift over their lifetime, or evolve from generation to generation (Gammon and Altizer, 2011). This should be researched more in the future, because there is no singular reason for why mockingbirds are able to mimic other songs. Even though mimicking is usually used most in a breeding setting, an experiment to learn more about this could open up pathways to different thought about bird song. An experiment concerning this would include taking juvenile mockingbirds at birth and raising them in a laboratory. Different experiments would include studying what songs are chosen by the mockingbird to mimic, and if mimicked songs are used purely for breeding or in other circumstances.

In addition, female song is only slightly researched in comparison to male song. It is assumed that female song is less complex, but this is just an assumption. One way of remedying this absence of research is to tag females as well as males and compare the two to illuminate differences as well as if female song has a mating purpose.