As a male amongst a crowd of receptive and unreceptive females, finding a mate to woo and carry your offspring is hard work! The common fruit fly (Figure 1), Drosophila melanogaster, must deal with this complex social scenario in addition to competing with other males for a receptive mate. You might even infer that successful courtship in fruit flies requires complex cognitive processing, including the ability to identify a receptive female though sensory cues. It has been previously shown that female Drosophila use olfactory cues to identify potential mates, though whether males also use these cues to identify female mates is less known (Dickson, 2008). In a recent publication, Hollis and Kawecki (2014) hypothesized that sexual selection contributes to the evolution and maintenance of cognitive abilities, such as olfactory discrimination, in male fruit flies. In other words, “smarter” flies may fare better in the mating game and consequently create more smart offspring.

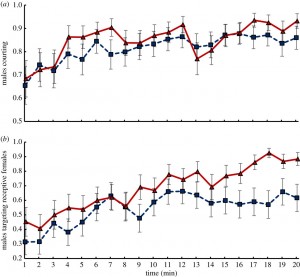

One way to approach the above hypothesis is to compare the behavior of male flies with and without sexual selection. To do this, Hollis and Kawecki maintained monogamous and polygamous (also known as the control) populations of flies for over 100 generations. Males in the polygamous group would naturally undergo sexual selection for increased ability to court receptive females, while this pressure was removed in the monogamous group, where each male was randomly paired with a receptive female. Here mating-adaptive abilities in males should be beneficial under polygamy and irrelevant under monogamy.

Figure 2. In an environment of one receptive and five unreceptive females, the proportion of males that are (a) actively courting and, if courting, (b) directing efforts to the receptive female over a 20 min period. [Click image to enlarge]

![Figure 3. One-hour olfactory memory score according to protocol of Hollid and Kawecki (2014). Learning scores are shown for (a) males and (b) females from monogamous and polygamous populations. [Click on image to enlarge]](http://pages.vassar.edu/sensoryecology/files/2014/03/F5.large_-191x300.jpg)

Figure 3. One-hour olfactory memory score according to protocol of Hollid and Kawecki (2014). Learning scores are shown for (a) males and (b) females from monogamous and polygamous populations. [Click on image to enlarge]

So why is it important to study the effects of sexual selection on cognitive ability in fruit flies? These insects are easy-to-maintain model organisms with relatively short reproductive cycles, making them ideal for evolutionary experiments. Moreover, the competitive sexual selection scenario that flies encounter is not much unlike what other organisms, including humans, experience. The next time you meet a potential mate, you might even consider the role sexual selection over generations has led to the cognitive abilities of the specimen in front of you.

References:

Dickson, B. J. (2008). Wired for sex: the neurobiology of Drosophila mating decisions. Science (New York, N.Y.), 322(5903), 904–9. doi:10.1126/science.1159276

Hollis, B., & Kawecki, T. J. (2014). Male cognitive performance declines in the absence of sexual selection. Proceedings of The Royal Society: Biological Sciences, 281(1781), 20132873. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2873