Environmental stress can cause adverse effects on an animal’s health via the pressure it places on behavioral and physiological processes. These effects may last throughout an animal’s life, especially when the stress occurs during early-life developmental stages. For example, the quality of the songs of male songbirds (repertoire and song length) relates to the environmental conditions in which the male songbird matured. Stress inhibits neural development of song control by limiting the animal’s attention and resources during essential developmental growth. Since birdsong is a sexually selected signal, female songbirds are affected by the variations in male songs that occur with differences in stress during development. To find the most successful male, females must be sensitive to the variations in male song quality for it alludes to the health and success of the male songbirds; therefore, song quality and perception closely correlates to reproduction success. Although we understand the fundamentals of how early-life stress impacts the quality of song in male songbirds, we know little about the effects of early life stress on female songbirds and their ability to perceive and process songs. To fully understand the evolution of sexually selected birdsong signals, this information is essential. This study attempted to determine the impacts of a specific stress, unpredictable food supply, on the development of female European starlings’ neural structures and on their preference of male songs, in terms of species and length of song. Species comparison was done between starling male song calls and canary male song calls, which show similar qualities, but are still noticeably different.

Auditory Neural Structures

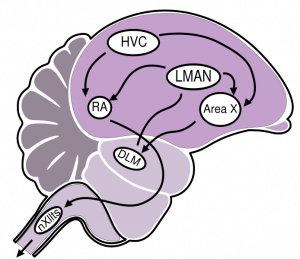

Female songbirds possess a song-control system (HVC) similar, although smaller, to their male counterparts. Additionally, the auditory forebrain nuclei in the brain, which includes the caudomedial mesopallium (CMM) and the caudomedial nidopallium (NCM), contributes to the recognition and processing of songs. Neural response within these areas can be determined through the assessment of Zenk—an immediate-early gene and transcriptional regulator. Zenk expression is greatest when birds listen to songs from their own species and decreases when they listen to songs of other songbird species. Since expression of Zenk has been linked to the sexual potency of a sound, by measuring Zenk expression levels, we can quantify female song preferences. The experiment analyzing Zenk expression considered the total number of Zenk-immunoreactive cells in three regions of the auditory forebrain—CMM, NCMd, and NCMv. Results concluded that females that listened to starling songs had significantly more Zenk-immunoreactive cells than those that listened to canary songs. Additionally, females that were raised in a food-restricted environment had reduced Zenk activation in comparison to the control females. This suggests that early food restriction during development adversely affects neural response to conspecific, or within species, songs and challenges the female starling’s ability to process male songs.

Female Song Preferences

Female song preference can also be determined through behavioral testing and assessments. Preference in behavior experiments can compare the reactions of female birds to songs from males of the same species versus males of different species and can also compare the preference for short versus long songs. Early food restrictions affected the preference for conspecific songs—the control group female starlings spent proportionally more time listening to and visiting a perch associated with starling calls than the food restricted females. Moreover, the control group females spent more time on starling call perches than can be attributed to purely chance levels. Song length preference showed no significant difference between the two groups. Birds were equally active around perches with varying song lengths regardless of the environment the female was reared. Some females did prefer specific lengths of calls; however, there was no directionality of preference that related to the development treatments. The results of the behavior studies suggest that early-life stress reduces female starling preference to their own species song over canary songs.

Conclusion

Female starlings express similar patterns to their male counterparts in terms of responses to stressful environments during their development. Food restriction during the development period of a female starling’s life affects her behavior and neural response to male starling songs. The results in the neural response studies here supported and reinforced the associated behavior studies. Stress reduced the number of Zenk cells, overall, in the auditory forebrain of starlings. These findings provide some of the first direct evidence that female song preference, like male song development, depends on external conditions. The food restricted group in these experiences, with limited neural responses and decreased perception of conspecific songs, would possess poorer mate evaluation abilities than those female starlings raised in the control group. Therefore, they would locate a mate slower and of lower quality than females who experiences less early-life stress. This disadvantage carries implications for female starling’s and male starling’s reproductive success in the face of possible rising anthropogenic stress that may occur during their early-lives.

References

Farrell, T.M., Neuert, M.A.C., Cui, A., MacDougall-Shackleton, S.A. (2015) Developmental stress impairs a female songbird’s behavioural and neural response to a sexually selected signal. Animal Behavior 102, 157-167.