Photo above: A boat wends its way through mangroves in the Everglades ecosystem. Phote credit to CARLTON WARD, JR

Photo Above: Cypress trees in the Everglades. Photo Credit to Terry Eggers.

The Everglades National Park in Florida is the only natural World Heritage site in America to land on the critically in danger list due to human population growth, development, invasive species and fertilizer drainage. As a Floridian I am saddened to learn this. I am also ashamed. I actually was not aware of this until learning it in class. I also was able to learn a lot more about the Everglades in my research for this post.

The Everglades National Park is listed as a World Heritage site, International Biosphere Reserve and a Wetland of International Importance. (National Parks Service) It is also protected under the Cartagena treaty. The Cartagena requires that all parties part of the convention take measures to protect and preserve rare or fragile ecosystems, and the habit of endangered species, within the convention zones. Their purpose is to prevent, control, and reduce pollution of these lands. (EPA)

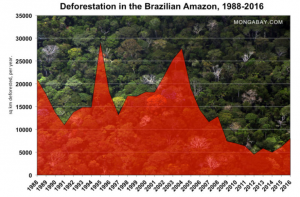

Once the Everglades covered over 11,0000 square miles of Florida, from Orlando down to the tip of the peninsula. It is now only 2,500 square miles with 1800 miles of canals and dams breaking up the natural system, thanks to human population growth and development since the 20th century. It contains a very slow moving river, 60 miles wide and over 100 miles long. (Lillie Marshall 2011)

The Everglades variety of wet habitats have made a sanctuary for numerous rare and endangered species. The sea turtle, American Alligator, Florida panther, and Bald Eagle are among several endangered species dependent on the ecosystem the Everglades provide. (Everglades Holiday Park Blog 2015) If the ecosystem were to continue to encroached upon and destroyed then many or all of these species would die out.

In addition to the animals and plants that depend on the land, the Native American Seminole tribe also depend on the land. Native people have inhabited the Everglades for thousands of years, and the Seminole tribe depends on the healthy ecosystem for survival. Traditional cultural, religious, and recreational activities, as well as commercial endeavors are dependent on the Everglades. Tribal members believe that if the land dies, so will they, because their identity is so closely linked. (Seminole Tribe of Florida)

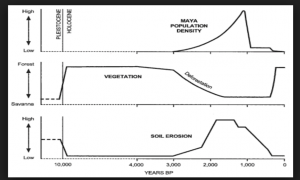

Archaeologists are helping to protect and restore this ecosystem. By looking at the archaeological record, they are able to observe and interpret lifestyle changes made by inhabitants as a result of the changing climate and landscape that occurred. This type of information can be useful to scientists and engineers working to restore an environment impacted as dramatically as the Everglades. (Thomas, 2013)

There are many other programs set up to help protect and restore the everglades. The Seminole tribe has the Seminole Everglades Restoration Initiative to improve water quality, storage capacity, and to enhance hydroperiods. Congress had passed the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan to restore, protect and preserve 18,000 square miles of land over 16 Florida counties. The National Park Service website also has many ways to contribute. Let us save this ecosystem and preserve it.

Links to Everglade restorative programs.

https://www.semtribe.com/Culture/SeminolesandtheLand.aspx

https://www.evergladesfoundation.org/the-everglades/restoration-projects/

https://www.nps.gov/ever/getinvolved/index.htm

More Information

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/the-conversation-us/restoring-the-everglades_b_10228720.html

Works Cited

“Cartagena Convention and Land-Based Sources Protocol.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 6 Dec. 2017, www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/cartagena-convention-and-land-based-sources-protocol.

“Culture.” Seminole Tribe of Florida – Culture, www.semtribe.com/Culture/SeminolesandtheLand.aspx.

“Everglades National Park (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, www.nps.gov/ever/index.htm.

“Everglades Wildlife: Threatened and Endangered.” Everglades Holiday Park, 5 Mar. 2015, www.evergladesholidaypark.com/Everglades-wildlife-threat/.

Marshall, Lillie. “Danger and Glory in Everglades National Park of Florida.” Around the World “L”, 26 Oct. 2011, www.aroundtheworldl.com/2011/07/26/danger-and-glory-in-everglades-national-park-of-florida/.

Thomas, Cynthia. “Archaeologists Help Preserve the Past, Link to the Future.” Jacksonville District, U.S Army Corps of Engineers, 19 June 2013, www.saj.usace.army.mil/Media/News-Stories/Article/479638/archaeologists-help-preserve-the-past-link-to-the-future/

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “Everglades National Park.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, whc.unesco.org/en/list/76.

Image Sources

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/national-parks/everglades-national-park/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/everglades-national-park-180952529/