Slavery has, unfortunately been a prevalent theme in most societies throughout all of history. When the average person in the United States thinks about slavery, they think of colonialism, African slave trade, plantations, and the Civil War, when Abraham Lincoln finally put an end to the madness. But slavery has happened so many times before, is happening today, and will happen again in the future. It is not merely a laps in moral judgment that happened during a specific time, like from the birth of the US to the Civil War, or while the Egyptians built the pyramids. The exploitation of slave labor is consistent part of humanity and should be treated as such.

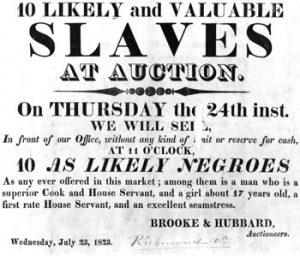

Many documents are valuable for the identification and study of slavery in the United States. These should be used along with archaeological methods for a thorough investigation.

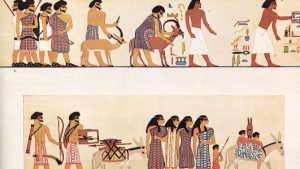

Up until the adoption of the post-processual approach to archaeology, any notice of slavery was done through historical written record. It was believed to be the only way of seeing slavery, that there was no way to know that slaves existed unless you knew they were there. Ropes deteriorated over time, and chains were often repurposed. But there are many ways of identifying the presence of slavery in the archaeological record. The places slaves lived, especially on plantations in the United States, were generally smaller and separated from the remainder of the house. It is often hard to tell if these quarters were for slaves, free blacks, or white servants. Sometimes with slaves, more effort was put into hiding their existence, and the house’s reliance on slave labor. Screens could be put up, or very elaborate alternative ways of navigating spaces, like different stairs etc. However, given such detailed and well-recorded accounts of slavery in the US, it seems counterproductive to not rely on both documentary and archaeological sources. But what about the places that have fewer or no written records? In ancient societies, slaves were taken from the defeat or sacking of other societies. The men were killed, and women and children were taken to be sold into slavery. This led to the idea that if more women were found on the archaeological record, then slavery was present in the society. Slaves are also depicted in frescos and paintings as smaller than other people in the picture.

Once slavery is “discovered” then what, and does it even need to be discovered? We know that 1 in 3 people in Italy during the Roman Empire were slaves and that they were integral to society. There are over 20 million people in slavery today. Nothing has changed. At this point, do we need to identify slavery? Or can we just “assume access to coerced labor… in the same way access to drinking water is assumed.” Some archaeologists want to shift the focus of the archaeology of slavery to the study of its effects and consequences, instead of merely whether or not it existed. These invisible demographics throughout history, like slaves, homeless people and migrants, can provide insights into the present and ways to tackle these issues right now.

Sources:

- Cameron, Catherine M., et al. The Archaeology of Slavery: A Comparative Approach to Captivity and Coercion. No. 41. SIU Press, 2014.

- Singleton, Theresa A. The archaeology of slavery and plantation life. Routledge, 2016.

- Mark Cartwright. “Slavery in the Roman World,” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified November 01, 2013. http://www.ancient.eu /article/629/.

- Ian Muir-Cochrane, Are there really 21 million slaves worldwide?http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-26513804

Image Sources

- http://www.history.com/news/5-things-you-may-not-know-about-lincoln-slavery-and-emancipation

- http://www.haaretz.com/jewish/archaeology/1.713849

Further reading:

- https://cliojournal.wikispaces.com/Slavery+in+Ancient+Greece

- https://www.antislavery.org/slavery-today/modern-slavery/