Harry Roseman with John Yau

by John Yau

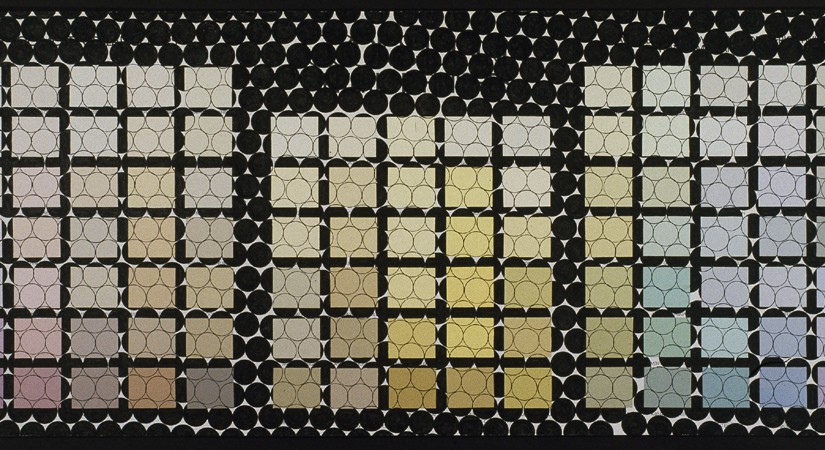

On the occasion of Harry Roseman’s recent exhibit 100 Most Popular Colors at Davis & Langdale Company, Inc., which will be on view until October 20, 2007, the Rail’s art editor, John Yau paid a visit to the artist’s studio in Hyde Park, New York, to talk about his life and work. Self-Portrait in the Mirrored Door of the Medicine Chest. 2006

John Yau (Rail): 100 Most Popular Colors is a series of 100 drawings that you did on paint color charts that one would get at a hardware store when thinking about painting a room or wall. Each chart consists of 100 sample squares of color, right?

Roseman: Correct. Each chart starts with blush white in the upper left hand corner and goes to violet.

Rail: The colors are pale, with no bright or primary colors. The project was to get 100 of the same color charts and do something to each one. In the first one, you covered the sheet with diagonal lines, which remind me of pick-up sticks.

Roseman: I use the color chart, words and squares of colors as a ground. It’s very straightforward.

Rail: And you do different things in each drawing; you draw only in the squares; you use a brush, a pencil, a rapidiograph; there are some where you use a razor blade to precisely and rather obsessively cut an X through each colored square from corner to corner, and then there are others where you peel the color square back or off.

Roseman: Some transitions are clearly sequential. I made lines over the whole chart in the first drawing. In the second one, I made similar, smaller marks only in each colored box. It was a conversation about the various parameters that were possible once the thing itself was, in a sense, talking back. At first I got a couple of different color charts and decided to start with this particular one 100 Most Popular Colors because it was a very simple grid, the colors were low key, and it was a kind of partner for me to talk to. I did one, and then another. And then it was one of those moments where I kept seeing the title of the color chart, which folds over like a triptych, and it’s called 100 Most Popular Colors. It’s a folded piece of paper with 100 boxes of insipid colors that look like they’re left over from the fifties. And I said, “100 most popular colors, 100 boxes, 100 drawings.” It seemed clear to me that there needed to be 100 drawings in order to achieve a total balance between each one and the whole enterprise. 100 Most Popular Color #97, 11 24 3/4 inches, black acrylic paint on color chart. Courtesy of the artist and Davis & Langdale Company, Inc. 100 Most Popular Color #94, scored and peeled color chart with black acrylic paint, 11 24 3/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Davis & Langdale Company, Inc..

Rail: And you atomize time by deciding to do 100 drawings in which you keep talking to the grid of muted colors. There is a performative aspect to some drawings, such as when you make a perfect physical circle with a drop of paint.

Roseman: Right, they’re not flat and drawn, they’re physical blobs of paint.

Rail: You did this methodically, one after the other, and you couldn’t miss the square.

Roseman: My process and my ideas about much of my work seem to be incremental. I’m very interested in things that build up by mark or dab, and sometimes you see it and sometimes you don’t. With the circle drops it’s apparent. The first rule for 100 Most Popular Colors was that I’d do them sequentially, and when I finished one, and if I was satisfied with it, I would sign it and number it. There was no editorializing to make a point. I also allowed myself periodically to be thrown off the path by outside experience, so there are drawings that seem to come out of nowhere. Take the cutting you mentioned. When I realized that I could cut and peel the color samples, it opened up a lot of possibilities.

Rail: Many things occur to me. One is that you define a formal process where a different thing has to be done to the piece, and it stays formal but all this incidental stuff happens that you couldn’t have planned for. In one drawing it looks like you’re paying homage to Joseph Albers, and in another it looks as if a monochrome painter has perversely miniaturized his or her entire career into a hundred paintings. And you go from the optical and tonal to the linear and sculptural, because there’s the drawing where you have peeled all 100 colored slips and piled them in the middle of the chart. There’s a fluid interaction among the sculptural, linear drawing, and optical, as if to say that the relationships among these things are not as cut off from each other as art historians would seem to say.

Roseman: I love that!

Rail: That fluidity makes sense within the larger body of your work. You do shallow reliefs that are pictorial, and, historically, relief exists between painting and sculpture.

Roseman: Yeah, it’s already a form that sits in the interstices of things.

Rail: In fact, your work sits in the interstices over and over again, and you can’t say it’s this or it’s that, because it is often both this and that.

Roseman: There are people who work out of theoretical ideas and start with a kind of stance. I don’t do that. I do the work that excites and interests me, it brings me where it brings me and I keep my fingers crossed. And then, like you just said, I don’t believe in “this or that” very much. It doesn’t mean there is no room for judgment or that no choice is being made. I make a lot of very specific choices and assessments. Sometimes it takes me a long time to figure it out, and sometimes it’s clearer, but I want to be the kind of person who can find enough sustenance and meaning in a very small arena, and I do. And when I’m working on things that sustain over time in a certain way, I’m in a very intense present tense where that could conceivably take me through the next fifty years. But then when I leave my studio, look at stuff, talk to people, my mind is racing and I’m getting ideas so that sometimes I will somewhat reluctantly follow these things and leave other things behind.

Rail: In your twenties, you took photographs of Joseph Cornell, which weren’t shown for at least twenty years. You started photographing when you were ten, and you’ve taken photographs your whole life. And there are the weave drawings, which came later than other things, but which you’ve also been doing for twenty years. Then there’s the bronze relief sculpture, the huge public sculpture that you did at JFK and in the subway station down near Wall Street, the recent painted sculptures that are both sculptures and paintings, and there’s this body of drawings done on a color chart in 1993-1994, and it’s a self-sufficient body of work within your project.

Roseman: A distinct body of work that talks very much to the other drawings I’ve done. And in some ways the chart’s use of tonal gradation has asserted itself in some of my sculptures. So as much as it seems like an idiosyncratic body of work, its tentacles reach out very fully to other bodies of work. My work is elliptical and parallel. There are parallel things going on which retouch base elliptically. One thing going through my work is my interest in compressed space and viewpoint, and they culminated in that first big subway project.

Rail: How so?

Roseman: What happened was, I had these big projects that take a huge amount of time. The airport project took four years; the subway project took a year and a half. I’m working and working, it leads to this commission, and there’s all this other work sitting in the studio. One big thing about the subway project goes back to this idea of being incremental. I made this little model, 7 by 41 inches, out of bits of clay, and then I had to do this huge version of it when I got the commission, and I couldn’t figure out how to get from those little bits or marks to the big surface. So finally I broke that code and the little marks looked bigger. During that year and a half, I was as interested in the pieces of clay, which were overlapping to make the surface that would look reasonable at that size, as I was in the landscape. So that threw me. I said, “It’s these marks that are so goddamn important.”

Rail: How do the drawings fit in?

Roseman: The 100 Most Popular Colors came between the subway wall and the curtain wall at JFK, when I was drawing a lot and thinking about weaves, pattern, and mark-making, and trying to figure things out. It made a lot of sense at that moment, and it brought in other things that I couldn’t bring in through some of the sculptures, like my interest in How to Draw books, pattern books and sample books. So I said, Oh well I can bring in my interest in increments, mark-making, weaves and gradation, and have a conversation with all this other stuff that I had to put on the back burner. It was a way to reground myself, and in a strange way, bring me back to a place where I was twenty years before.

Rail: I also think that succinctness and linearity are really illusions. There’s a Romantic notion of the self as this goal-directed figure that possesses a certain number of self-defining gestures or actions, and my sense from your work is that you don’t buy into that illusion at all.

Roseman: For better or worse, I don’t!

Rail: I mean you say that you’re this self at one point and this self at another because you’re really saying, I don’t know the particular self I am because I’m many different possibilities and I want to keep them all in play at all times.

Roseman: You were saying earlier that I did photography, and I did these drawings; the thing about photography that I would like to say specifically is that, like a lot of people who become artists, I drew all the time. But probably a little more idiosyncratically, I have also taken photographs since I was a kid. That was something I always did, almost like breathing. I had a darkroom when I was a kid, so I did developing and printing. I don’t know at what point I went from thinking I was taking pictures to thinking I was making photography. At some point, probably in high school, I said it’s photography. But, it still was something I just did, like riding a bicycle. And then I was learning about becoming this other thing—an artist—and I went to Pratt and made serious art and stuff, but I was still photographing and taking it seriously; it was always…‘there.’ But, somewhere along the way when I was already making sculpture, and I was having a life as a showing artist, and I had worked for Joseph Cornell from ‘69 to ‘72, life intervened. You know, twenty-something years after Cornell died, Deborah Solomon got in touch with me because she was writing a biography of him and wanted to know if she could talk to me and maybe use some of my photographs for the book. That changed two things. The photographs became more public. And I had this exhibition of this body of work about Cornell. Now Cornell had been dead for many years. And there were two issues, one was photography and its meaning within my overall enterprise, and the other was the Cornell photographs. I thought very hard about letting Deborah use the photographs, and also about showing them, which had nothing to do with my going public as a photographer, and had more to do with my going public about my relationship with Joseph Cornell. I mean, I love his work, I was extremely fond of him, it’s not like I was embarrassed. I was just cautious about having too early an association with such an icon. But by the time twenty-five years passed, I was quite grown up, and also had enough of a place in the world on my own as an artist that it stopped worrying me, so I showed those photographs. And then the photography became more public. Some of the conceptual photographic projects I’m working on now—which is a big part of what I’m doing with my website—started quite early as cognizant ideas. I started doing self-portraits in ’68; I started doing the “visitor series” in ’71. So already, besides hoping to take some really good single photographs, I was conceptualizing the enterprise in a way that had to do with being self-conscious. Some of the projects are incremental, like the weave drawings. Taking a picture of everyone, including the UPS man and plumber, who comes to your house is about time; it is diaristic and incremental, like “The Bolt.” I’m making these bodies of work that build in a totality of one plus one plus one plus one, you know, 100 plus 100, etc, until the work starts to perk and make sense as a kind of undertaking with authority. I think that Mark Lombardi and I shared an interest in interconnectedness. Mine is more social and cultural, his more political. I think about those beautiful drawings of his that have this purpose of showing connections and I could see drawings like those talking about my group project. Even though I wouldn’t do it and it doesn’t interest me to do it, it’s another parallel way to think about how to present something. And talking to you, for the first time, I think maybe it’s a way I could think about my whole body of work; where you have these threads—like weaves (weaving is always such a great metaphor for all sorts of connectedness)—where you can make connections that show relationships.

Rail: That makes sense. Let’s talk about “The Bolt” because you mentioned it. You bought a good amount of muslin—

Roseman: Right, a bolt of cloth—

Rail: You’ve been drawing on it since 1989.

Roseman: Like my weave drawings on silk, “The Bolt” is a drawing that is also an object. It’s an incremental weave structure that is very depictive because it looks like a real weave, I’m just kind of metaphorically weaving while drawing and it is a certain length and I work on it somewhat every year. It will be another length eventually. It’s about counting minutes, and making marks, and making an object that exists as an object. It’s much more about process than a finite making of a thing. If I only worked on “The Bolt” for the next ten to fifteen years, which, as I told you, if I was a totally enlightened person, it’s probably what I would do, and then I would be humming all the time, and I’d be one with the universe and no one could ever talk to me because I’d be somewhere else, even though physically I’d look like I was here. But anyway, I work on it steadily, and when I die it will be done. Maybe not complete, but done. It is a very esoteric, and, in other ways, a very straightforward operation. Actually, the fact that I still work on it is a way for it to come with me, because I hate leaving things—when my work changes, as I told you, I get sad. No, I’m not making the milk carton still lifes anymore, why can’t I do that for the next forty years? Which I could, but I can’t. And so the fact that “The Bolt,” which I have shown a few times, and I’ll show it again, is and always will be a work in progress, I’m not secretive about it.

Rail: And then there are the collages you did at one point.

Roseman: You might recall, I did those tissue boxes, and they had this weave pattern on them. And then I started drawing these weaves and those overlapped with the subway project as well. And the collages were a little bit of an aside in some way but they led me to the weaves. How to Draw books were just something I liked and kept thinking that they could mean something, and they finally did when I drew in them. And they led me to the 100 Most Popular Colors. The collages just came out of the fact that—you know, we all do collages when we’re in art school or high school—I also had all this stuff! I had diagrams, books, boxes of stuff that had these images, and I think I made the collages as much to make things as really an excuse to cut things out; because I think there was probably a year when I just cut things out and wasn’t making collages. It was very satisfying.

Rail: Did you categorize them when you cut them out?

Roseman: Yeah, I have books and boxes of tools, pieces of cloths, cars…

Rail: Do you know Jess’s work?

Roseman: Yes, I love Jess’s work.

Rail: When I went to his house he showed me his drawers and drawers of stuff, and they’d be labeled like, Butterflies, Men Working, Cars.

Roseman: Yes! Exactly! You know there’s something, and maybe he had the same feeling, about looking at a book, or a whole picture, and extricating a thing. And the extricated thing might be flat like a drawing, or it might be three dimensional or photographic, and then it exists as a discreet thing. And so there’s the cutting, which is very pleasurable, and I used to say while I was cutting, I don’t see why anyone says they are bored, they could just cut things out. I titled one collage “Inventory” and another “More Inventory.” I did a really big collage, that I never finished, and which I may go back and finish, of hundreds of hammers tight together. Again, I think it goes back to that thing of, through the cutting, which is its own pleasure, the incremental, the additive, the building-up, to make something; like alchemy, more than the thing.

Rail: Okay, but then, just to go back, there’s this other side to you, like in this 100 Most Popular Colors. Somehow the serious never overwhelms the playful, but more importantly the playfulness overwhelms the serious.

Roseman: I think they’re simultaneous. The new relief sculptures, they’re very meticulous. I know I’m not talking about 100 Most Popular Colors, but they’re very precise, and elegant in a way, because of their singularity and simplicity. I’m having a conversation with Ellsworth Kelly and I’m having a conversation with cartoons. There’s something a little bit about the color, I mean they’re not really Kelly colors, but they are these soft simple shapes that are one color so I think of him a little bit and of cartoons.

Rail: Also a little like Richard Tuttle.

Roseman: Yeah, a little bit, in a way, yes, in my own, very different way.

Rail: At the same time you’re not being ironic.

Roseman: You know, I must say; one of the things I am really very rarely ever in my work is ironic. I don’t embrace irony in my work.

Rail: So that’s what you mean by a conversation, because irony is a judgment, and you’re not passing judgment if you’re making work that bounces off or has a conversation with—

Roseman: I’m not even making judgments about these How to Paint books. I’m not doing it as social satire, I’m doing it out of fascination. I mean, I look at those things. It’s a kind of love-hate thing; I think they’re silly, and I love them! And when they show you how to make these little highlights on things, there’s accomplishment in that. And even though what it results in is pretty bland, and you get to the same place all the time, it’s fascinating.

Rail: Yeah, I always thought there was nothing ironic to your work, but there is an immense amount of playfulness which I think is different.

Roseman: It is different. And I would embrace the playfulness, and be really upset if the work was ironic. Because I like meaning what I am doing and its value and the value of the things I’m referring to and the finding of value in all kinds of quirky places. Real value, not kind of winking-at-value. That doesn’t interest me.

Rail: It’s interesting that you mention cartoons and Ellsworth Kelly because you’re really talking about what was foolishly called High and Low Art by Kurt Varnedoe, and saying there’s a fluid connection, why make distinctions between them?

Roseman: I mean, again, there’s crap and there’s not-crap. I’m more than willing to make those distinctions. You know. But I don’t think that supercedes what we’re talking about. I mean on one level I can’t look at work by Thomas Kinkade, but at the same time I can see what’s in it that I can have a real conversation with. You know, just as I feel I can have a real conversation with someone who liked that stuff. What is that about? That would be curious to me. And when I choose to have a visual conversation in these drawings, boy, it’s not about poking fun. It’s about what’s in there that I can talk to that will change what I’m doing and change how I or someone might look at that stuff. Not to elevate it, but to just be open to the dialogue.

Rail: Right. And that’s how 100 Most Popular Colors came about.

Roseman: Right, and I collect more things than I will ever use and I never know what’s going to slip in and become a viable visual discussion at any moment that’s going to be exciting to me. And at a certain point, probably cause of my imploding from the subway wall, I got an opportunity to do this.

Rail: And the other thing that really strikes me about it is that it’s not arty, this piece. I mean you’re beginning with something—the material itself—and you’re making us look at something we don’t normally look at. And you kind of get us thinking are these really the 100 most popular colors. (Laughs)

Roseman: (Laughs) Yeah, that’s a little disheartening! When you are working with color charts the question of taste is naturally present. I find that taste is the thing unspoken. As artists, we are often propelled and embarrassed by the underlying impetus of taste, which fascinates me.