By Halle Hewitt and Sixing Xu, under the guidance of Professor Thomas Ellman

We were accepted as Ford scholars for Professor Ellman’s summer video game project. Professor Ellman was interested in video games’ potential as an interactive medium through which players could look at a social justice topic in a wholly new way. We decided to create a game focusing on the Syrian refugee crisis. The mass migration of refugees fleeing the civil war in Syria (due to fighting between supporters of and dissenters to the Assad regime, and with several groups, including ISIS, taking part) began in 2011 and continues today. Unlike many other ongoing refugee crises, the Syrian refugee crisis currently claims the attention of mainstream Western media. One of the main reasons for this is that the majority of Syrian refugees are Muslim; many Westerners associate practitioners of Islam with membership to ISIS. However, racism and xenophobia are also significant factors that have played a role in Western countries’ discomfort with and even animosity towards refugees and immigrants throughout history. With recent terrorist attacks by ISIS in the West, the reluctance to resettle refugees has only increased. However, the number of Syrian refugees that have resettled in Europe, Canada and the U.S. hardly compares to their vast numbers in countries neighboring Syria, namely Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan.

We wanted to focus our project on the media (e.g. news videos, interviews, websites, statistics on the refugee crisis, as well as the art made by Syrian refugees and/or about Syrian refugees. For members of the Vassar community, as well as for many people around the world, there is no direct way of interacting with Syrian refugees. Consequently, we rely on media to understand this crisis. While we may agree that there is no such thing as objective media, we often choose to isolate ourselves with media that only support our already-incubated beliefs. This is true especially when the particular society we surround ourselves with reaffirms these beliefs for us, or, to put it another way, pressures us into conformity.

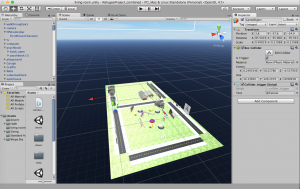

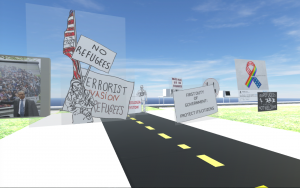

We divided our work: Sixing made a desert with two abandoned buildings, containing media either made by Syrian refugees, or made from close interactions with them. The primary focuses of these media are art and music. Halle made a suburban house and block containing more mainstream, and mainly Western media, as well as comments made by refugees and non-refugees on social media platforms like YouTube and Twitter. We made just one object in the suburbs that, if the player found and had enough interest in, takes them to the desert. Otherwise, they would remain in the suburbs for the duration of the game.

The project is an amalgam of perspectives — perspectives from here, from the computer and TV, from the itty bitty talks on the dinner tables, and those from elsewhere: the faraway Middle East, the real happenings in refugee camps, unseen art and music made by refugee artists and children, the raw images that are covered by those screens in our living rooms, hidden by the more accessible Western media. You can’t be two places at once in real world, but in virtual worlds, it’s easy to be here and be elsewhere.

Our final product will do its work as an educational resource on the Syrian refugee crisis, but other than that, it is about the way we see, hear, watch, perceive and understand. The explosion of media in our lives successfully gives the false impression that we learn and understand issues more quickly, effectively and deeply; but at the same time, we are too drowned in the sea of information to realize that the excess of media is obscuring us.

We hope what we made can at least expose the fact that we are in an age where we need to think critically about what we perceive through media. But critically how? Is there even a right answer to a question like that? We have been looking for that answer throughout the project, and we will always in the pursuit of it — not from here, not from elsewhere, but in between here and elsewhere.