Climate change represents the most daunting crisis our world faces today. Global efforts toward carbon neutrality, however, are not happening fast enough. As a small liberal arts institution, Vassar is well suited to experiment with innovative strategies to reduce its own emissions, and set an example for other organizations. My research explored the feasibility and potential effectiveness of using a carbon tax and/or carbon accounting at Vassar to reduce our carbon footprint. My coworkers and I conducted research on the theory of the ‘social cost of carbon,’ interviewed representatives from companies like Microsoft, Google, and Facebook that have implemented an internal carbon tax, and visited Yale to discuss their innovative carbon charge model that will be implemented this academic year.

Carbon emissions result in an incurred cost to society. Carbon pricing seeks to internalize this externality by setting a price on the per/ton value of carbon emitted. The EPA calls this price the ‘social cost of carbon,’ and currently estimates the value at $40 per metric ton of carbon dioxide emitted (EPA 2015). Incorporating carbon pricing into operations has the potential to reduce emissions, prepare Vassar for an externally imposed carbon tax, create educational opportunities for students and faculty, and to distinguish Vassar as a leader by setting an example for the rest of the country.

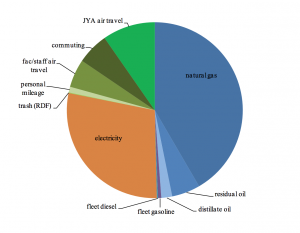

Carbon pricing can be incorporated into accounting processes or used as an internal carbon charge. Integrating carbon pricing into accounting could shift capital project decision making from short-term to long-term prioritization by illustrating the relative lifetimes of their carbon footprints. There are two primary models for a carbon charge. The central fund model, currently used at Microsoft, imposes a tax on emission-intensive products like gasoline or electricity. At Vassar, this could mean charging departments directly for their total electrical, heating, or transportation use, and allocating the raised funds for carbon-reduction investments. Alternatively, Yale’s approach redistributes funds between departments based off their relative annual emission reductions, thus achieving “revenue-neutrality” for the college while incentivizing behavioral change.

The feasibility and effectiveness of different models need to be explored further, so a white paper of our findings will be issued and a task force will be created to determine which model, if any, is appropriate at Vassar.

Work cited: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “The Social Cost of Carbon.” 2015. http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/EPAactivities/economics/scc.html