In the introduction to elite New Englander Christiana Holmes Tillson’s account of her experiences in Illinois in the early 1870s, historical novelist Emerson Hough challenges the conventional paragon of Western expansion characterized by “the long-haired, fringed-legging man riding a raw-boned pony.”[1] Instead, Hough identifies “the gaunt and sad-faced woman sitting on the front seat of the wagon” as the “chief figure of the American West.”[2] He goes on to challenge our collective memory of the Western woman in her sunbonnet and profoundly asks, “Who has written her story? Who has painted her picture?”[3]

Hough’s critical questions perceptively frame my role in Professor Rebecca Edwards’s ongoing research on the significance of women’s fertility and reproduction in U.S. electoral politics, territorial expansion, and conquest. For four weeks this summer I researched Western narratives and diaries to better understand the ways in which men and women conceived of frontier motherhood and to paint a collective portrait of these frontier mothers from their own perspectives. I also assisted Professor Edwards in compiling and analyzing U.S. Census data and large families’ genealogical records to identify trends and patterns in family size, literacy rates, and other pertinent information.

Census and Genealogical Records: Professor Edwards and I combed through the 1900 U.S. Census and compiled data on mothers in various Southwestern counties. Our main focus was compiling information on families in a Southern frontier county to gain a better understanding of the size, make-up, and social status of this specific subset of Southwestern families. The trends that we identified illuminate the drastically differential experiences that mothers at the time could have had depending on a variety of factors, including age, race, literacy, and class. The existence of women who bore over ten children was not all that uncommon, yet the child survival rates at this time were abysmal, particularly for African-American children. For example, the average child survival rate of African-American mothers born before 1845 was only 39%, while the average child survival rate for white mothers who bore fourteen children in their lifetime was closer to 64%. As evidenced in women’s narratives, the phenomenon of extremely large families and shockingly high birth rates corresponded with a relatively high child mortality rate; although almost every woman’s diary from the time is replete with mentions of family members and friends giving birth, passages dedicated to the untimely deaths of these children are almost as frequent.

Women’s Narratives: As the Census and genealogical data demonstrate, women in the early to mid-nineteenth century, particularly Southern women, routinely married at a very young age and were thus able to start their childbearing careers quite early on. Early marriages were a common theme in women’s reminisces and diaries, yet not all women accepted this social custom. Elvina Apperson Fellows, born in Missouri in 1837, married a forty-four year old man named Julius Thomas in 1851 soon after she arrived in Oregon at the behest of her mother. She was just fourteen years old at the time. As Fellows describes, “What could a girl of 14 do to protect herself from a man of 44, particularly if he drank most of the time, as my husband did?”[4] Sarah Haynsworth Gayle, a mother of six who moved to Alabama in the early 19th century, expressed similar sentiments on such early marriages. She vehemently opposed the marriages of young teenage girls and described how “Old Dr. Merriwether has taken a third wife, having buried his last about eight months ago – he is seventy seven & she seventeen… There is something really shocking in the idea; something wrong too, for a good virtuous girl would have encountered poverty in its most hidious [sic] form, rather than have made the sacrifice so repugnant to nature and to reason.”[5] In addition to the controversial topic of teenage marriage, Gayle’s journal is preoccupied with the social visits of friends and family members. Gayle was subsumed in a network of mothers who provided advice and assistance in the details of bearing and raising children, as well as consoling figures when these children died in infancy.

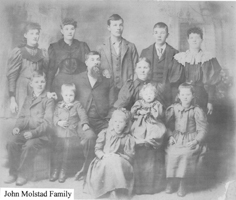

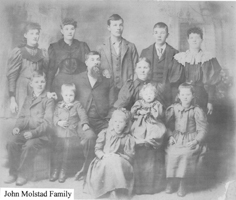

John Molstad and his wife Petronelle Rosedahl Molstad moved from Norway to Dakota Territory in the late 1800s. Petronelle had already birthed five children in Norway and went on to birth six more after arriving in pioneer territory, all of whom helped maintain the family’s 160 acres of land. Ten of the Molstad children are pictured above with their parents. Source: www.marisaannebenson.com/petramolstad.html.

Because many women married at such a young age, the size of frontier families often grew to be quite large in a relatively short period of time. In collecting the Census and genealogical data, it was not uncommon to come across women who had birthed over six, eight, or ten children. In Chicot County, Arkansas, we identified twenty-seven women, all African-American, who bore sixteen or more children, including two who were mothers of twenty and one who bore twenty-three.

Christina Holmes Tillson, an elite New Englander who moved with her husband to Illinois, described the difficulties of raising even a few children on the frontier. She frequently described how fatigued she was at raising her handful of children without any help. The particular difficulties and conditions of frontier life certainly took its toll on pioneer mothers.

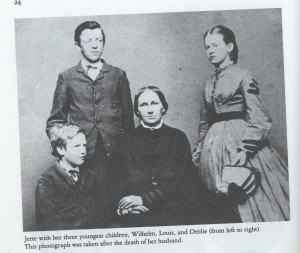

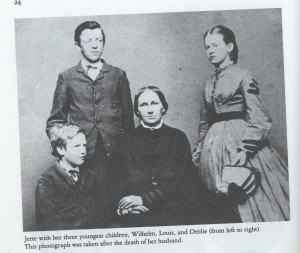

This devastating toll that motherhood could have on women of the frontier generation was perhaps no more evident than in the story of Henriette “Jette” Bruns, a native German who immigrated to Upper Louisiana with her family in 1835.  Jette birthed eleven children in her lifetime, yet five died in childhood. Jette’s life in America was extremely challenging and disheartening. These sentiments are perhaps best summed up in Jette’s declaration that “it is no fun to represent cook, nursemaid, and housewife in one person.”[6] These difficulties that frontier women experienced in their attempts at inhabiting so many roles and managing the myriad of responsibilities that accompany childcare were often exacerbated by the frequent occurrences of various maladies and diseases. In 1841, one of Jette’s older children, Bruns, returned from a trip to St. Louis with dysentery. Jette described how “In a few days all of our children were sick. Hermann survived the illness, but the little ones! Johanna died on the 13th of September, Max on the 19th of September, and the babe in arms, little Rudolph, followed on the 2d [sic] of October. With all of them the last words and the dying glance was ‘Mother!’”[7] Jette’s three youngest children therefore died within three weeks of each other. The youngest, Rudolph, was not even a year old.

Jette birthed eleven children in her lifetime, yet five died in childhood. Jette’s life in America was extremely challenging and disheartening. These sentiments are perhaps best summed up in Jette’s declaration that “it is no fun to represent cook, nursemaid, and housewife in one person.”[6] These difficulties that frontier women experienced in their attempts at inhabiting so many roles and managing the myriad of responsibilities that accompany childcare were often exacerbated by the frequent occurrences of various maladies and diseases. In 1841, one of Jette’s older children, Bruns, returned from a trip to St. Louis with dysentery. Jette described how “In a few days all of our children were sick. Hermann survived the illness, but the little ones! Johanna died on the 13th of September, Max on the 19th of September, and the babe in arms, little Rudolph, followed on the 2d [sic] of October. With all of them the last words and the dying glance was ‘Mother!’”[7] Jette’s three youngest children therefore died within three weeks of each other. The youngest, Rudolph, was not even a year old.  In light of these devastating events, Jette wrote to her brother that he “would be disappointed in me, and you would have only sad memories when I had left you again. There is none of the youthful freshness left, but instead a stiff, sad, indifferent figure, without manners, without interests, with aged features, a mouth without teeth.”[8] Jette’s story, although quite extreme, encapsulates the complex of difficulties, disappointments, and hardships that frontier women often faced.

In light of these devastating events, Jette wrote to her brother that he “would be disappointed in me, and you would have only sad memories when I had left you again. There is none of the youthful freshness left, but instead a stiff, sad, indifferent figure, without manners, without interests, with aged features, a mouth without teeth.”[8] Jette’s story, although quite extreme, encapsulates the complex of difficulties, disappointments, and hardships that frontier women often faced.

[1] Milo Milton Quaife, introduction to A Woman’s Story of Pioneer Illinois, by Christiana Holmes Tillson (Chicago: The Lakeside Press), xvi.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Fred Lockley, Conversations with Pioneer Women, ed. by Mike Helm (Eugene: Rainy Day Press, 1981), 65.

[5] The Journal of Sarah Haynsworth Gayle, 1827-1835: A Substitute for Social Intercourse, ed. By Sarah Woolfolk Wiggins and Ruth Smith Truss (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2013), 47-48.

[6] Hold Dear, As Always: Jette, A German Immigrant Life in Letters, ed. By Adolf E. Schroeder and Carla Schulz-Geisberg (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1988), 79.

[7] Ibid, 111.

[8] Ibid. 157.