With the second Sonic Cyborg Residency’s end last night, I take the opportunity to reflect on the first. At the end of February, Vassar hosted Michael Chorost and Trevor Pinch for said residency. Each gave a lecture on his respective relationship with cyborg-ism. On February 24th, I found myself in Taylor Hall for Chorost’s lecture.

Perhaps I shouldn’t say I “found myself” there. I didn’t happen upon the lecture hall; I consciously chose to go. I found something within myself, though: an overwhelming sense of naivete regarding cyborg technologies. So I sat in the crowded room, mind open, an expert on the subject at the podium.

Perhaps I shouldn’t say I “found myself” there. I didn’t happen upon the lecture hall; I consciously chose to go. I found something within myself, though: an overwhelming sense of naivete regarding cyborg technologies. So I sat in the crowded room, mind open, an expert on the subject at the podium.

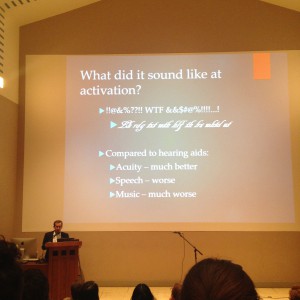

Chorost first relayed to us that he abruptly went deaf in the summer of 2001. Despite having worn hearing aids before, that July was the first time his hearing had entirely dropped out. Since then, he has benefited from technology engineered to help restore one’s hearing: a cochlear implant. After this background, Chorost listed several theoretical implications for such technology and finished by fielding questions from the large audience. Therefore, the lecture was aptly titled “What It’s Like to Go Deaf and Get Your Hearing Back with an Implanted Computer (And What That Means for Theory).”

Of the implications he covered, one resonates with me the most: “[p]opular culture is naive about [the] learning curve and effectiveness of cyborg technologies.” He expressed his concerns in this regard by sharing his experience receiving the surgical implant, one for which he “was completely unprepared.” In an hour alone, Chorost managed to, at the very least, begin bridging that gap in knowledge. Consider the context in which an individual would most likely learn about such implants: if they know someone who has/needs one or if they have/need one themselves. Since “only 5.6% of people who would benefit from a cochlear implant have a cochlear implant,” according to Chorost, the chances of such learning occurring are low. Therefore, the number of people even partially-informed about these implants is low. As such, certain systems are not in place to accommodate them. For instance, spaces can be encircled with a wire, or a loop, that allows individuals with cochlears to tap into the sound waves in the room. While we were fortunate enough to have said loop donated for the lecture, looping is far from commonplace. Even one of the audience members conveyed disappointment that America as a whole isn’t making more of an effort to make such systems more accessible. We should all do our part and get involved, educating ourselves out of that naivete. The pieces in his ears are not magic. They are not bionic ears. They are cochlear implants, technology that is changing all the time to better suit those who choose to use them. Advocate for this important cause. Help bridge the gap.