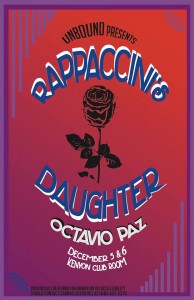

On December 5th and 6th, Unbound performed Rappaccini’s Daughter at the Kenyon Club. This adaptation of Octavio Paz’s play, based on a short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne, complicates notions of moral dualism. Paz reimagines Hawthorne’s Rappaccini’s Daughter and presents a nuanced, surrealist take on it. Unbound further explored these ideas in its show through set design, lighting, and other choices.

On December 5th and 6th, Unbound performed Rappaccini’s Daughter at the Kenyon Club. This adaptation of Octavio Paz’s play, based on a short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne, complicates notions of moral dualism. Paz reimagines Hawthorne’s Rappaccini’s Daughter and presents a nuanced, surrealist take on it. Unbound further explored these ideas in its show through set design, lighting, and other choices.

The action takes place in a corridor with audience members on either side. A beautifully intertwined installation of strings, evocative of a tree, extends from one end of the corridor to the other across the ceiling. A number of black, fruit-like structures hang from this tree, whom Beatrice identifies as her brother.

Nymph-like entities, which are really plants, set the stage with an ethereal mood. They move in a dreamy fashion, and their alternating voices appear as thoughts for us to ponder on. They subside into inertia as other actors emerge onstage. The lighting is dim and ambiguous.

Giovanni, a guest whose room faces the luring garden, inquires about the girl that lives there, Beatrice. She’s the daughter of Rappaccini, a medical researcher of sorts. As he is promptly informed, she and her father are ‘poisonous,’ in that they scheme to harm those that near them. Mesmerised and terrified by this notion, Giovanni resolves to seek out Beatrice regardless of the warnings against her.

Sterne, in Hawthorne Transformed: Octavio Paz’s La Hija de Rappaccini, argues that the poison signifies the mutual alienation of woman and man, not love versus sex or sin; while the central theme is the ardent quest for a lost unity, and the individual’s effort to escape from the prison of the self. Thus Hawthorne’s strictly oppositional symbolism is transformed by Paz into a series morally murky identities that are exciting and unexpected to us, the viewers.

In the garden, Giovanni is drawn to Rappaccini’s plants. These artifices, originated from the wit of the medical researcher, are alluring to him because of their ‘otherness.’ The plants are virtually engineered and thus previously unknown, which only makes Giovanni more eager to possess them. This compulsion to appropriate what is seen as ‘exotic’ and ‘othered’ is symptomatic of a need for self assertion through acquisition of property. The fact that the play itself isn’t named Beatrice, but Rappaccini’s Daughter, shows how she is defined and even controlled by her relationships to men as opposed to an identity of her own. It’s a male-dominated narrative where Rappaccini is literally the creator and Giovanni the discoverer of his creations. They validate the existence of the plants and Beatrice, who are limited in mobility to the confines of the garden, and react to change rather than effect it.

A relationship founded on power, where Giovanni is the ‘discoverer’ of Beatrice’s femininity, implies that no previous value existed in Beatrice’s subject before it was found by Giovanni. In other words, Beatrice (the object) only exists when seen or possessed by the subject (Giovanni.) When Beatrice’s agency defies her father and Giovanni’s authority by attempting self-determination, she becomes anxious and fears their reaction.

Ultimately, Beatrice chooses to drink the potion Giovanni gives her. This choice is both an undeniable exertion of her agency, as well as an act of resistance against possession. She knows not what awaits her after death, except for an escape that can drive her further or closer to herself. It’s not a reaction against patriarchal oppression, but a demonstration of her ability to be the architect of her own fate, culminating in a return to nothingness.