On Friday September 19th, a gorgeous day not unlike this one, I had the pleasure of visiting the art exhibits on view at Vassar through December of this year. The first is “Never Before Has Your Like Been Printed: The Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493” in the Main Library, the second is “Tongues in Trees: Xylography and the Uses of Adversity” in the Art Library, and the third is “Imperial Augsburg: Renaissance Prints & Drawings, 1475-1540” in the Loeb Art Center. I strongly encourage everyone to go see the incredible artwork that each of these exhibits has to offer. Here’s what happened when I did just that:

—

Comprehensive List of All the Things I Know About Nuremberg: A List Composed in My Head While Walking to the Main Library

- city in Germany

- location of the Nuremberg trials (post World War II, Nazi leaders on trial)

- proper noun

- starts with an “N”

Discouraged, I quickly abandon this whole “listing” idea as I walk up the library steps. Upon entering, I’m about 80% sure that the exhibit is in the hallway under the main archway on either side. Rather than trusting my gut, I inquire at the front desk just to be sure. “It’s in the hallway under the main archway on either side,” the librarian replies politely, pointing to it. Feeling silly for asking, I thank her and walk over. Upon arriving, I realize she could’ve said, “It’s literally straight ahead by the huge blue sign that very clearly reads ‘Never Before Has Your Like Been Printed.'” I appreciate her discretion.

The exhibit reads from left to right, beginning “by locating Nuremberg and showing a contemporary view of the city and a map of the neighborhood where several participants in this project lived,” according to the exhibition catalogue. Each of the items on display are titled and elaborately captioned. The first reads “Nuremberg” and goes on to provide its historical significance and geographic location, the page a sea of reds and whites and greens. The next describes the Chronicle as “A Community Project,” part of an attempt to produce a “history of the world.” It goes on to discuss the artists and others mainly responsible for the Chronicle. I’m caught off guard by the religious and biblical imagery, as stories of Adam and Eve and God and Abraham jump out at me. It’s not that I find the subject material problematic; I just wasn’t expecting it. Though, since the goal was to create a history of the world, I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised since the bible aims to do the same. And it succeeds: the “Influence” display calls the Chronicle the “first German description of the world.”

Speaking of a specific language (i.e. German), the Chronicle was written in two: Latin first, and then German. Thus, it makes sense that the hallway on the left focuses more on the Latin version and the one on the right focuses on the German version. A former Latin student, I get possibly too excited when I realize I can translate the Latin pages. For whatever reason, it doesn’t dawn on me at first that these are the real pages of the Latin edition. So, I assume that the images are real but the writing is the nonsensical “lorem ipsum…” Latin placeholder text. I’ve never been so glad to be wrong. The Latin is real and it’s beautiful and I love it. But I digress. About 1300 Latin copies and 600 German copies of the Nuremberg Chronicle were printed in the late 1400s. Interestingly enough, the Chronicle was reprinted in Ausgburg, another German city featured in the three exhibits. And these Augsburg Reprints were more popular and sold more than the originals.

While geeking out over the Latin and beauty of the Chronicle in general, something dawns on me: I’m the only one who’s looking at this exhibit. I’ve been walking up and down this hallway for an while now and no one has so much as glanced at it. Well, that’s not entirely true. Two of my friends stopped to see what I was doing and one girl glanced at the stack of exhibition catalogues before going on her way. Anyone else just gave me a weird look as they passed. Though, in their defense, I was probably quietly singing the Jonas Brothers to myself and the library really isn’t the place for that. That aside, the lack of attention the exhibit was receiving was and still is very disheartening. Maybe things will be different in the Art Library.

Something dawns on me while walking to the Art Library: I’ve never been there before. I’ve never so much as been in the little courtyard between the Main Library and the Art Library. That in mind, insert ten minutes of me wandering the stacks, exploring the different floors, and trying to open every closed door I see here. After properly situating myself, I climb a narrow set of stairs that leads me to the “Tongues in Trees” display. Again, no other students are here, the woman at the front desk my only company. I walk to the center of the room. In a large clear glass display case sit the eight items that make up the exhibit, all created by either Frans Masereel, Werner Pfeiffer, or Stanley Donwood. A book dedicated to each of these artists is sitting on a shelf right across from the display. Unlike in the Main Library, these items are not accompanied by descriptions of any kind, only numbers (1-8) that correspond with those on the checklist on the back of the exhibition brochure.

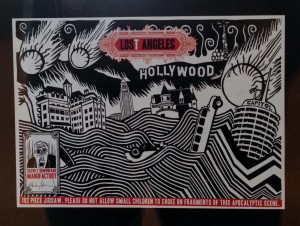

Two of these black and white woodcut works strike me more than the others. The first is Out of the Sky: Remembering 911. With two five foot towers covered in a collage of body parts at the bottom and the names of the victims at the top, Pfeiffer has created an extraordinarily powerful 911 memorial. Additionally, a catalogue of those who lost their lives that day accompanies the towers. The second item that really strikes me is a 192-piece jigsaw puzzle by Donwood called “Lost Angeles.” As a Los Angeles native, the title alone catches my eye. Then I notice the disclaimer in red and white at the bottom of the puzzle box top, the red a stark contrast to the black and white of the puzzle itself. It reads: Please do not allow small children to choke on fragments of this apocalyptic scene. Caught off guard, I laugh to myself. Donwood is right, though; this is an apocalyptic scene. Buses and cars are overturned, becoming enveloped in a massive flood. Meteors are moments away from crash landing into buildings. Several fires rage in the background. All the while, the Hollywood sign, the only word on the entire puzzle, stands tall near the center of it all, untouched. The irony in this image is as fantastic and hilarious as it is saddening. In this contradictory mindset, I leave the Art Library.

The following day I head to the Loeb, as the “Imperial Augsburg” exhibit did not open until later Friday night. Maybe it’s because this is the first full day the exhibit has been open. Maybe it’s because the exhibits in the Main and Art libraries were put in place to compliment this one. Maybe it’s because this is an actual art center, not a library with a small section of art in it. Whatever the reason may be, I am far from the only one wandering through the 4-room display of Renaissance prints and drawings of Imperial Augsburg from 1475 to 1540. Yes, there are four entire rooms covered in woodcut works and steel armor and bronze medals. As with the other exhibits, many of these pieces are in black and white, with few bits of color. In certain cases, there are multiple versions or “states” or some pieces, the first in black and white, and the second with hints of color.

In addition to the placards next to each item, larger placards title and describe each section of items in the exhibit. The first is an introductory section: Augsburg: Cultural Golden Age in the Late 15th and 16th Centuries. It perfectly categorizes all of the items in the first room you enter. I pass a man taking notes and a woman examining items with a magnifying glass (I’m not joking…) as I head into the second room. Two contrasting placards situate the items in this room. To the right, one reads The Power of Women and Everyday Morality: Virtues and to the left, one reads The Power of Women and Everyday Morality: Vices. As expected, the virtues and vices of women in Imperial Augsburg are the focus of this room. The last two rooms have less of a unified feel than did the first two. They focus on the following: color printing, citizens and daily life, ornaments (i.e. medals), and Maximilian I. I find myself moving through these two more quickly, noting that fewer people accompany me into each new room. I am virtually alone in the fourth room of the exhibit except, of course, for the security guard who keeps cutting his eyes over at me. I don’t appreciate his indiscretion.

So, CAAD readers, grab your friends and your friends’ friends and head over to any (or all) of these three exhibits on campus. The next time you’re listening to a lecture in Taylor Hall, stop by the Loeb on your way out. The next time, or first time for some people, you’re in the Art Library, take a moment and explore Lost Angeles for yourself. And the next time you’re in the Main Library and need a study break, check out the first German description of the world located in the hallway under the main archway on either side. There’s a huge blue sign; unless you’re me, you can’t miss it. Then, let us here at CAAD know what you think!

~ peace, love, and creativity ~