Many proud dog owners wouldn’t doubt for a second the intelligence of their canine companions. Not only does it seem like your dog simply “gets you,” some even argue that their dog comprehends human languages. However, this sort of talk is often both speculative and subjective, as measuring verbal comprehension is complex enough in humans; we simply don’t know how to get inside a living dog’s head yet. Before anyone gets on my case for dismissing their pet’s intelligence, I would like to introduce a recent study showing that dogs can use referential auditory stimuli to locate food, even after controlling for visual and olfactory stimuli. Yes, you were right; your dog is smart, and here is something you can use to make that a stronger argument.

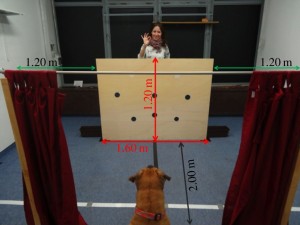

Figure 1. The general experimental conditions, with an experimenter and subject dog separated by an opaque barrier, and containers (one of which holds food) on both sides of the barrier. Click for larger image.

Referential auditory stimuli refers to calling towards a goal object. Rosano et al. (2014) developed an experimental design where the experimenter and a subject dog is separated by an opaque barrier (Figure 1). Food is placed in one of two containers and the two containers are presented on each side of the barrier at the same time. Next, the experimenter squats behind the barrier, but closer to the no-food container, while orienting an excited voice towards the food container. Under these conditions, subject dogs preferred (moved towards on the first try) the food container significantly more than the no-food container.

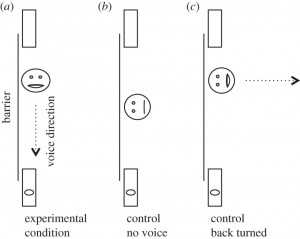

Figure 2. An illustration of the three experimental paradigms where (a) voice was directed at the food box, (b) no-voice control (to test of olfactory response), and (c) back-turned control (to test for the referential component of auditory stimulus). Click for larger image.

Given this interesting result, which suggests that dogs can comprehend the direction of voice and prefer it over the source location of voice, you might wonder if simply the smell of food in one container will be powerful enough for a dog to immediately move towards it. The researchers therefore repeated the aforementioned experiment without voice, so only the olfactory cue is detectable, and showed that dogs did not prefer the food container more than chance would allow. Moreover, the researchers also tested if the referential component of auditory stimuli was important by repeating the experimental conditions, but with the experimenter directing her voice towards the wall. During this paradigm, the dogs again did not successfully prefer the food container. Altogether, the results of three experimental paradigms, illustrated in Figure 2, show that subject dogs responded to excited voices directed at a reward.

Figure 3. Adorable puppies!

The ability to refer to referential auditory stimuli is a useful skill, especially considering that domestic dogs live in homes where they are almost completely dependent on a human benefactor for food. As a dog, you would not want to miss out if your owner tells you there is food over “there,” but you can’t quite see where she is pointing. However, is this skill innate or learned? The researchers found a clever way to test this by repeating the experimental conditions with puppies (Figure 3)! Fortunately, the researchers had access to puppies that lived without much human contact or with a lot of human contact. It was found that puppies with substantial human contact performed as well as adult dogs in preferring the food container using referential auditory stimuli. Puppies without much human experience contact did not perform as well. Thus, while the ability to detect and use referential auditory stimuli in dogs may be innate, it might also be a skill that results from human contact.

What does all this matter besides providing bragging rights for your dog’s intelligence? This study can be applied to all domesticated animals, whose primary ecology is the home or human-populated environments. It is important to understand how animal behavior has adapted both via learning and evolution to better sense and survive in such places. This will also help clarify the confusion in the scientific community exactly how wild wolves and their domesticated counterparts (dogs) differ.

Source:

Rossano, F., Nitzschner, M., & Tomasello, M. (2014). Domestic dogs and puppies can use human voice direction referentially. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1785), 20133201.

Clever experimental setup. Just one annotation: “The ability to refer to referential auditory stimuli is a useful skill, especially considering that domestic dogs live in homes where they are almost completely dependent on a human benefactor for food.” – Well, may I suggest that this capability originated not in the homes of affluent Western people in cities as we are used to now. In my opinion it makes more sense to think of the early stages of domestication: when a dog lived together with human beings who e.g. lived in tents or caves there were (at least) three scenarios where auditory cues would have value to their OWNERS (less the dogs – the dogs who behaved not to the owners standards were either disowned or killed). One would be in a hunting environment. The other two would be: a) auditory cue TOWARDS the intended food source and b) auditory cue to tell the dog to keep AWAY from the edible stuff that humans had reserved for themselves! I think the latter alternatives would be testable as well.