In class this week we learned about how immigration policy in the United States has made life hell for many of those attempting to cross the border into our nation. Most of the border is protected by security, while one stretch in the harsh and unforgiving Arizona desert is left unprotected as a “natural deterrent”. Thousands of immigrants have

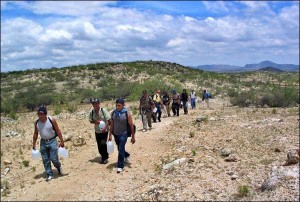

A group of immigrants attempting the trek across the US-Mexican border. As you can see, they are carrying plastic jugs of water to stay hydrated, although the water likely is not enough.

died in that harsh environment just trying to make it across (lots due to lack of water), and many made it here just to get deported back to their home countries. That might change soon, thanks to some recent activity at the White House.

Just this past Thursday, President Obama signed an executive order aimed at giving more protection to undocumented immigrants. According to the order, undocumented migrants who have been in the

United States for at least five years will be able to apply for a government program that protects them from being deported and allows them to work legally in the US without facing potential criminal prosecution. In addition, more migrants will be protected from deportation through reforms to the United States’ immigration enforcement system.

What does this mean for immigration into the United States, and how do we apply archaeology to this question? Well, archaeological researchers have found that immigrants are perfectly willing to undergo the trek through the desert rather than immigrate through parts of the border a with less dangerous climate but more heavily guarded by the United States border patrol. Moreover, these immigrants often depart without the supplies they need to keep a lower profile. Examples of this are the imitation Nike sneakers worn instead of hiking boots (which are not as good at protecting the feet but make them look more like Americans) and the black plastic water jugs used by some (which heat up their water but are supposedly “less visible”). An executive order making it easier for immigrants who make it across the border to stay in the country will undoubtedly make immigration to the United States more enticing for those living in Latin American nations. In addition, since this order was not accompanied by a loosening of security on the parts of the border that do not lie along the Arizona desert, the increased number of immigrants trying to cross over will undoubtedly funnel through the Arizona/Mexico border and many will die. So, Obama’s new policy will lead to not only more immigrants (who might not have before wanted to cross over into the US due to fear of deportation but now feel that they will be safe) but to more deaths in the desert. A potential solution to this problem would be to set up water stations on the border.

Sources:

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/20/us/politics/obamacare-unlikely-for-undocumented-immigrants.html?_r=0

http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/soc/immigration/uploads/TestPagecrossingborder.jpg

Additional reading:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/27/us/27water.html

http://www.fronterasdesk.org/content/9772/movie-examines-illegal-immigration-arizona-border

http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/immigration-border-crisis/arizona-residents-protest-arrival-undocumented-immigrant-children-n155941

http://undocumentedmigrationproject.com