Today’s post comes from Samuel Blanchard, class of 2018 and Art Center Student Docent.

America’s commercial fashion industry is amidst a love affair with fine art

Tag Archives: pages.vassar.edu

Chemical Warfare Dates Back to Ancient Times

In the 1930s, a puzzling discovery came about in a siege mine at the city known as Dura-Europos in Syria. This city was controlled and run by the Romans as a military base backed by the Euphrates River, only until the powerful and overwhelming Sasanian Persian Empire made a push for the city. The Persians, however, did not go about this raid in a traditional way by any means.

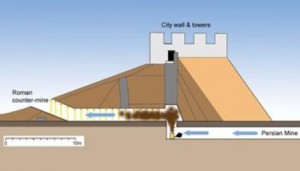

The Romans had established a large garrison to protect the city from any foreign invaders. Persian forces had recognized this, so they designed a mine to be dug underneath the city wall in an effort to collapse it. Romans soon became aware of this and dug out a counter-mine, which ultimately led to the death of 19 Roman soldiers and one lone Persian.

Diagram that shows the Persian mine designed to collapse Dura-Europo’s city wall, the Roman countermine which intended to stop them, and the possible location in which the Persians began to use the Chemical warfare against the Roman defense

Now how did the Persians manage to take down 19 Roman soldiers in such a tiny space? As the two different tunnels connected, the Persians had put together a form of chemical warfare, which to my surprise has been around for a significant period of time. Stephanie Pappas writes, “One of the earliest examples was a battle in 189 B.C., when Greeks burnt chicken feathers and used bellows to blow the smoke into Roman invaders’ siege tunnels.” The Persians used a chimney effect to gas out the Roman soldiers as the two mines met. Recent excavations revealed bitumen and sulphur crystal remains that provide evidence that those crystals were burned in order to create choking gases. The soldiers that were discovered were found stacked on top of each other to form a human wall for the Persians to continue on with their plan of taking the walls down. With how the Roman soldiers were found, and the position in which they were in, archaeologists determined that the Persians successfully pulled off the chemical combat.

Even though the Persian’s were successful in setting up their plan to bring down the walls, they still were unable to actually bring them down, however, evidence shows that they still were able to break into the city. University of Leicester archaeologist Simon James excavated a ‘machine-gun belt’ which looked to have been the Roman’s last line of defense that was never put into effect. One can infer that the people of the city were either slaughtered or driven out of the city, leaving Dura-Europos abandon forever. Although there was not much physical evidence at hand, archaeologists were able to figure out just what went down at this ancient city based on the 19 dead soldiers found in the mines.

Sources:

1. University of Leicester. “Archeologist Uncovers Evidence Of Ancient Chemical Warfare.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 15 January 2009. .

2. http://www.livescience.com/13113-ancient-chemical-warfare-romans-persians.html

Pictures:

1. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/01/090114075921.htm

2. https://gatesofnineveh.wordpress.com/2012/05/10/more-inventions-of-the-ancient-near-east/

Further Reading:

1. https://gatesofnineveh.wordpress.com/2012/05/10/more-inventions-of-the-ancient-near-east/

2. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/09/05/poison-gas-ancient-syria-chemical-warfare_n_3876017.html

3. http://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/archaeology/people/james/roman-soldiers-in-the-city/final-siege

4. http://io9.com/5798230/ancient-chemical-weapons-that-were-ahead-of-their-time

Modeling Conflict: WWI and Trench Warfare

The archaeology of warfare encompasses much of human history and extends to all corners of the globe. Although war has been a recurring theme across cultures, few individual wars remain fresh, scars on society’s collective memory. World War One, deemed the “Great War,” is one such instance where a combination of time, place, and scale culminate in an event of far reaching proportions. The soldiers who fought left behind records in letters, journals, and even art, but their legacy continues on a larger scale.

The battle of Messines led up to the much larger battle of Ypres. At Messines, the men worked for approximately 18 months preparing fortifications, and in the actual battle there were close to a total of 50,000 casualties and injuries. What makes this site of particular interest lies not on the battlefield, but rather at the Brocton and Rugeley training camps, located in England. During the war, these facilities were used to train allied troops but also to house prisoners of war. These camps are, of late, the focus of an Archaeological investigation focused on a specific area, known as Cannock Chase, which since the war has become overgrown from disuse. Under this reclaimed field lies the remnants of a large-scale construction project.

An actual trench from Messines

Built by soldiers with a great deal of labor from prisoners of war, the trench system at Cannock Chase perfectly matches that of Messines in 1917. The only difference is the location and size. Why, during a war, would allied forces spend time constructing a scale model of a battlefield that was subject to change at any minute? This seems a tactic of little use in today’s age of urban warfare, but in its time Cannock Chase served several important duties. First and foremost, they served as invaluable training tools for new infantry forces. The fighting at Messines stretched out over several years, and during that time trenches changed sides and forces shuffled across a barren wasteland. By using these model trenches, officers were able to prepare their troops for the exact environment they would soon face. The trenches were quite literally a chessboard where officers could safely shuffle troops about, practicing maneuvers and attempting new tactics. By training in these trenches, soldiers also became accustomed to the lay of the battlefield at Messines before they set foot in the actual war zone.

Part of Brocton and Rugeley Camps where the trenches are located

What can this site tell anthropologists about warfare? Well the answer is not quite clear yet, but with the mapping and excavation these fortifications should yield insight into the daily life both of prisoners of war but also the allied forces preparing to enter the real trenches. It is hoped that this model will help historians and archaeologists learn more about the actual battlefield at Messines, for the site at Cannock Chase remained largely unoccupied and undisturbed after the war. Until the investigation is complete, these trenches remain another of conflict covered up by time, with the promise of new information in store for those studying the site.

Sources:

1.http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2408820/Archaeologicial-dig-begins-unearth-scale-model-World-War-Ones-bloodiest-battlefields-created-survivors-Staffordshire-field.html?ito=feeds-newsxml

2.http://www.staffspasttrack.org.uk/exhibit/chasecamps/archaeology.htm

3.http://www.firstworldwar.com/battles/messines.htm

Pictures:

1.http://ww1revisited.com/2014/02/21/ww1-german-trench-messines/

2.http://www.pasthorizonspr.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Messinesheader.jpg

For More Information:

1.firstworldwar.com

2.ww1revisited.com

Wonder Women

Wonder-Woman, Xenu Warrior Princess, and Katniss Everdeen are today’s interpretations of Greek history’s elusive group of Amazon women. This all female tribe is usually associated with violence, war, infanticide, mutilation, and overall aggressive ruthlessness. People claim that the Amazons removed one of their breasts for more effective archery, killed any male sons, and were all homosexual because of their deep hatred for men. These legends have led the public to believe that Amazons are a myth. However, archaeologists today are finding more and more evidence suggesting the existence of “Amazons,” who are far different from their monstrous reputation.

Now to separate fact from myth: although the fantastical image of a wild tribe of women has proven to be just that, there is real evidence of ancient women exemplifying Amazonian traits. Recent excavations of Scythian kurgans (burial mounds of the nomadic Scythe population) have found female remains buried in the same fashion as warrior men–with bows, knives, daggers, tools, and hemp-smoking kits. Just like the men, their remains had war injuries. This was not a marginality either; in fact one third of Scythian women were buried this way. These findings deconstruct the idea of male burials. Rather, this ceremonial type of grave was that of an ungendered warrior. Although Amazons may not have been their own separate force, there were certainly women of Amazonian character that fought alongside men. Such rules out the origin of their respective warfare to be in reproduction, one of the four main causes for war along with territory, status, and nationalism.

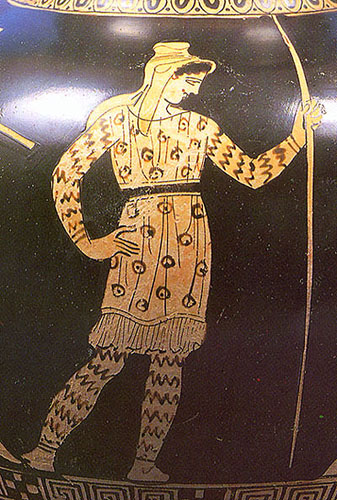

The striped legs of this female warrior show her wearing trousers, which were invented for riding horses and were uncommon amongst both men and women at the time.

Scythian warrior women had a strong bond of sisterhood, which although never suggested in antiquity, were today assumed to be lesbians. This may have been true based on the Greeks’ comfort with homosexuality. Still, evidence suggests they were not regarded as lesbians, but man-lovers.

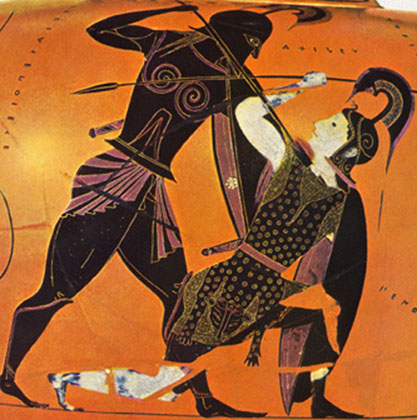

Depictions Amazon-esque women in pottery sanctified them as symbol of beauty, courage, strength, and war-spirit. In the 1300 images of Amazonian battles found in Adrienne Mayor’s studies of the infamous women, only two or three of them show signs of gesturing for mercy. They were horsebacked, arrow shooting heroes.

This image shows Amazon queen Penthesileia killing an inferior male warrior

With all of these suggestions of power, beauty, and greatness, why do we have such a negative, malicious view of the Amazons? I believe this to be a result of one of the pitfalls of archaeology: that it can reflect our present ideologies more than the past. Historically, women haven’t been viewed as valiant. We usually don’t teach history of women fighting under a male alias, or leading troops. Because the notion of heroic warrior women in our culture is so unheard of, it’s easy to rationalize the idea by dehumanizing these women. In androcentric interpretations of archaeology, it would seem more feasible for there to be crazy, animal-like lesbians on the loose than accept the fact that women may have been just as valuable and honored as men in wartime. It’s time to use proper feminist archaeology to rethink past gender roles so that we can celebrate Scythian warrior women rather than vilifying them.

Sources:

Article: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/10/141029-amazons-scythians-hunger-games-herodotus-ice-princess-tattoo-cannabis/

Images:

Image one: http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/dictionary/Dict/image/amazon2.jpg

Image two: http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/dictionary/Dict/image/penthesileia3.jpg

Interested in more about the Scythian warriors like the Amazons? Of course you are:

http://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends/tattooed-scythian-warriors-descendants-amazons-part-one-001155

Art Center Slow-Down

Today’s post comes from Rosa Bozhkov, class of 2017 and Art Center Student Docent.

On Wednesdays at three, we meet