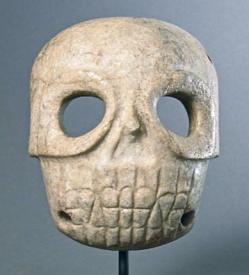

Three fossilized hominid skulls were found near Herto, Ethiopia in 1997. The skulls were determined to be those of two adults and one child. The remains were too old to be dated using radiocarbon dating. In order to determine the age of the artifacts found at Herto (Figure 1), scientists performed argon-argon dating on volcanic rock that was found near the artifacts (Zielinski 2008).

Figure 1. A map showing the location of Herto, Ethiopia, the village the hominid skulls were found near.

There are multiple radiometric methods of dating artifacts. Some of these radiometric methods include radiocarbon dating, potassium-argon dating, uranium-series dating, and fission-track dating (Renfrew 2010:120-129). Potassium-argon dating, which measures the ratio of potassium-40 to argon-40, is one radiometric method, but this method of dating is not as precise as argon-argon dating. Scientists converted potassium-40 to argon-39. This allowed the scientists to use argon-argon dating. The volcanic rock analyzed by scientists at Herto were found to be around 154,000 to 160,000 years old (Zielinski 2008).

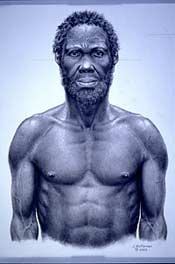

The hominid skulls found at Herto are important discoveries because at the time of their discovery, they were some of the oldest near-modern human remains on record (Graham 2003). Based on archaeological artifacts like the ones found at Herto, artists have created depictions of near-modern humans (Figure 2). The Homo sapiens remains found at Herto, which were distinct from Homo neanderthalensis remains, were given a subspecies name, Homo sapiens idaltu. Other artifacts from the same time period were found near the fossilized skulls. Some of these artifacts include stone tools and animal bones with marks from tools. Additionally, cut marks on the skulls are indicative of the mortuary practices and rituals of the early humans (Sanders 2003). These marks and tools, which include hand axes, help the people of today understand how Homo sapiens lived over 100,000 years ago.

Figure 2. An artist’s depiction of a near-modern human.

Scientists claim the analysis of the Herto hominid skulls supports claims made by molecular anthropologists. Before the discovery of the Herto artifacts, molecular anthropologists have claimed modern humans evolved out of Africa (Sanders 2003). The discovery of near-modern human skulls in Herto, Ethiopia supports this Out of Africa hypothesis. Before the discovery of the Herto artifacts, other Homo sapiens remains had been discovered in Ethiopia and other African countries. The ages of these other remains range from 80,000 years old to 130,000 years old (Sanders 2003). Since the discovery of the Homo sapiens idaltu fossils near Herto, remains found in Jebel Irhoud, Morocco have been found to be about 315,000 years old, making them the oldest Homo sapiens remains on record (Callaway 2017). While the Herto remains may no longer be considered the oldest Homo sapiens remains on record, the discovery was important in the understanding of the origins of Homo sapiens and illustrates the importance and usefulness of radiometric dating methods like argon-argon dating.

Additional Content

An article that details the importance of dating methods in the Herto discovery and other discoveries: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/showing-their-age-62874/

An article about the Jebel Irhoud Homo sapiens discoveries: http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/06/world-s-oldest-homo-sapiens-fossils-found-morocco

References Cited

Callaway, Ewen

2017 Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species’ history. Electronic document,

https://www.nature.com/news/oldest-homo-sapiens-fossil-claim-rewrites-our-species-history-1.22114, accessed September 19, 2018.

Graham, Sarah

2003 Skulls of Oldest Homo sapiens Recovered. Electronic document,

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/skulls-of-oldest-homo-sap/, accessed September 19, 2018.

Renfrew, Colin, and Paul Bahn

2010 Archaeology Essentials. 2nd ed. Thames & Hudson, New York.

Sanders, Robert

2003 160,000-year-old fossilized skulls uncovered in Ethiopia are oldest anatomically modern humans. Electronic document,

https://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2003/06/11_idaltu.shtml, accessed September 18, 2018.

Zielinski, Sarah

2008 Showing Their Age. Electronic document,

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/showing-their-age-62874/, accessed September 18, 2018.

Image Sources

Amos, Johnathan

2003 Oldest human skulls found. Electronic document,

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/2978800.stm, accessed September 19, 2018.

Sanders, Robert

2003 160,000-year-old fossilized skulls uncovered in Ethiopia are oldest anatomically modern humans. Electronic document,

https://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2003/06/11_idaltu.shtml, accessed September 18, 2018.

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/new_tattoo_631.jpg)